Professor Keyla Hernandez

Scale and proportions in architecture are fundamental core factors used to define, understand and design space. These two factors establish the relationship between the collection of parts, thresholds, and context. Scale, arrangements, and adaptations will

help determine the connections, adjacencies, overlaps, and layers between architecture, site, and landscape. This studio will investigate /look at the built environment as a series of contained worlds that will hold samples of new environments. These samples will be then deployed and stitched together to produce a new whole. Using advanced digital tools students would develop techniques to disassociate conventions of ground, landscape, and buildings. The goal of the studio is to experiment with sampling and containment of strata to investigate its scale and proportions and how it can produce alternative worlds within an encapsulated environment.

Riley Anderson

Cetus

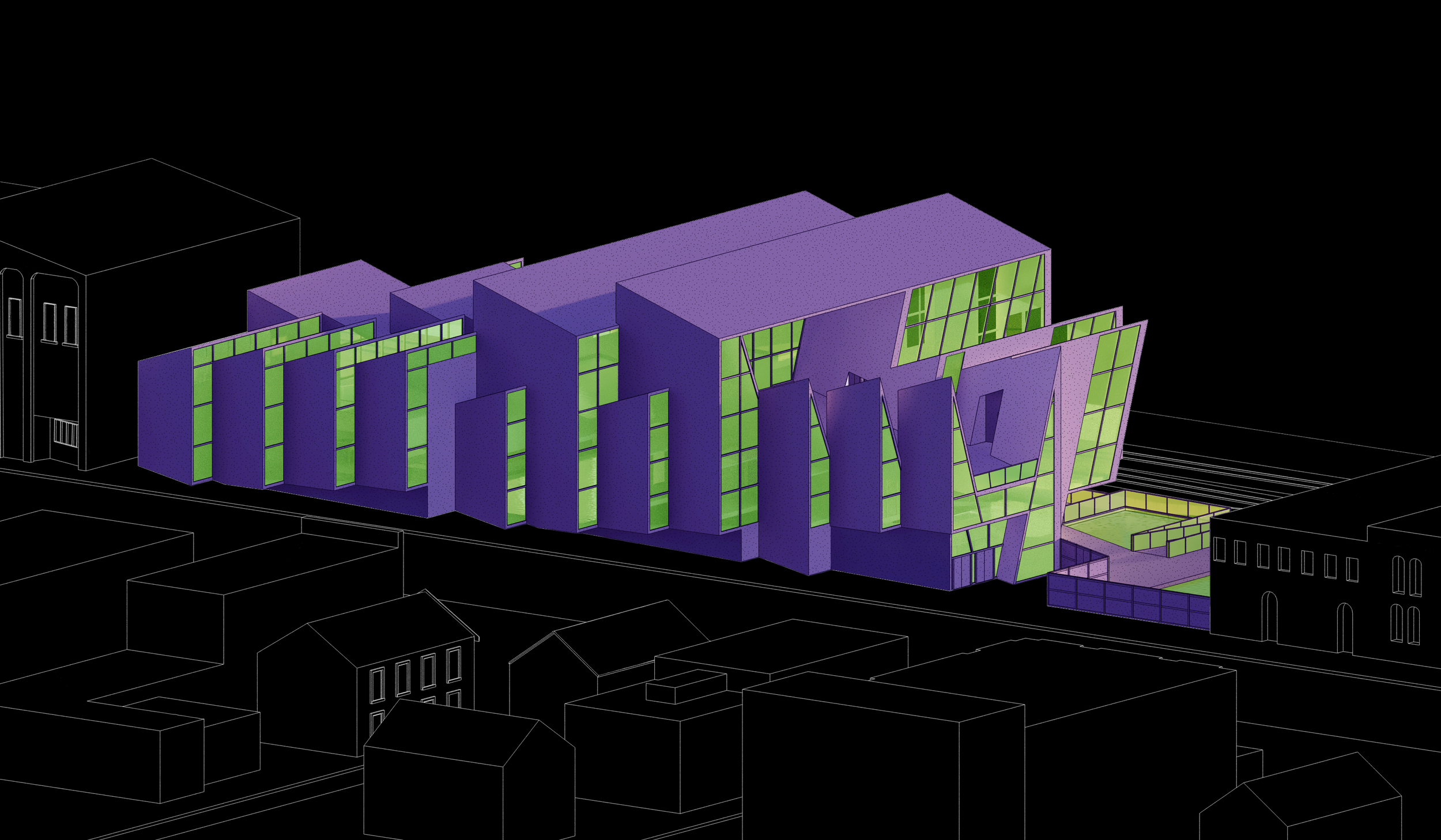

Navigating this project mimics traveling through the body systems of a living creature. The jagged, sawtooth configuration reorients the Eastern and Western facades to allow for North and South-facing glazing in the form of daylight windows and clerestories. These windows run vertically, and the clerestories are placed high on the walls to improve daylight penetration into the project. View windows overlook the Cuyahoga River. These windows run horizontally and are placed lower on the wall to allow for views while minimizing harsh daylighting and overheating from Western solar exposure. Voids are introduced across multiple floors to allow for daylight penetration and views throughout the project. The largest among these voids in the atrium over the cafe space.

In plan, the facades and roof form 20ft wide bands running East to West. The interior layout aligns to this grid as well as further subdivisions of this grid. Walls and other forms running East to West are linear, while walls running North to South are typically sheared to match the angle of the sawtooth facade. Shearing is less common closer to the center of the project and more common closer to the building envelope. The pool areas are grouped at the South end of the building across multiple floors. To ensure thermal and acoustical comfort, the pools areas are either enclosed or the smaller programs around the pools are enclosed. Views to the pool areas can be found throughout the project, making the swimming programs a focal point while navigating the building.

Sam Schroeder

162 Aquatic Center

The project is derived from a system of previous organic and mechanical pieces which combine to create a building implying movement. Grounded into the site by a cloud piece overhanging on both ends, this creates the first formal movements which the animal produces itself around. Through pipes and sheathing, the project displays its mechanized self. Water being the dominant element, the environment on and inside the project are formed for the containment and displacement of large volumes.

Stephanie Akhigbe

Swimming in Proportions

The main goal for our final studio project was to take elements we implemented when creating environments for the creatures we studied earlier in the studio and use them to create the form of our aquatic center. For my work, I wanted to focus more on creating a space that felt open yet enclosed. I also wanted to create interesting moments within the building where the tendril-like forms, adopted from the creature's environment, function as both structure and aesthetic.

Professor Jennifier Meakins

"""What is “site”? To architects it is the base and start of any project, it can be cleared ground, existing infrastructure, an entire city block. It is the boundary, the past and present geological, social, and political conditions, it represents both horizontal and vertical delineation. All sites first exist as places, containing collective memory, histories, stories of occupation, production, displacement, conflicts, that are often appropriated as “context” to be used or ignored as necessary by architects and developers for gain.

All of the United States, North America (Turtle Island) is stolen land, not just as a past result of settler colonialism, but as a present and future product of white supremacy and capitalism. What does this mean for architects, how (or) do we build on sites that were and are places that do not belong to most of us? That aren’t truly vacant or unoccupied, but are places of rich and sacred significance and resources?"""

Nicole Lanese

Loosening the Border

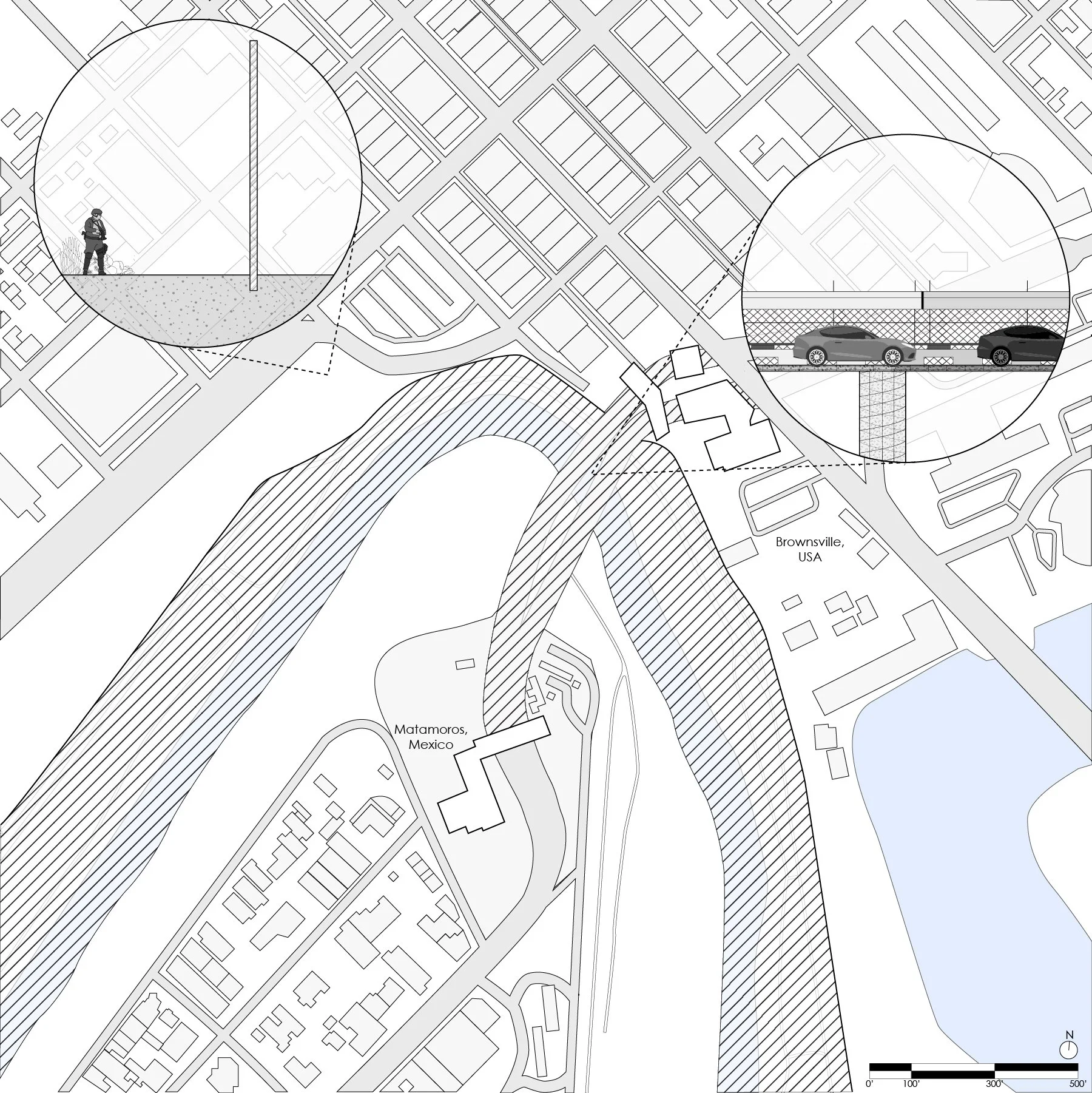

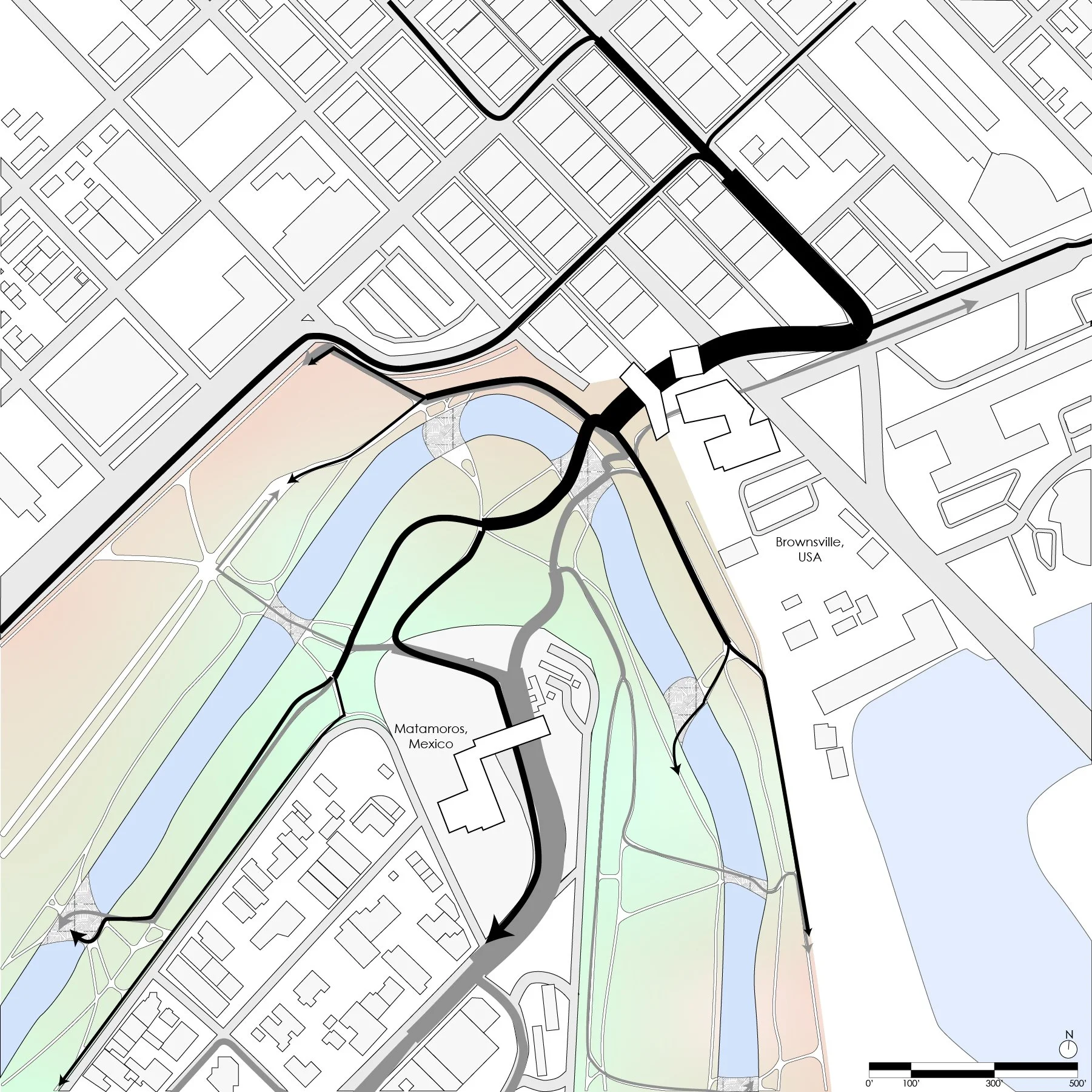

"Through the exploration of ground as boundaries, my research led me to the US-Mexico border. Europeans have long viewed rivers as boundaries and brought this mindset to their colonization of North America, leading to one of the most controlled borders being partially placed along the Rio Grande. This conceived divide is in heavy contrast to the Native population’s views of the river as a resource, not a separator. The Rio Grande is now a site of separation and control as intense border patrol keeps the communities apart; even bridges across the Rio Grande do not act as a connector but as another form of control.

If we instead look at the border as not a line but rather a region, control is reduced and interaction between the two communities is revived. The proposal reimagines the Gateway International Bridge to revive the connection between the two cities."

Lake Erie Center For Marine Ecology and Conservation | Professor Robert Kobet

The goal of our section of 3rd Year Option Studio is to merge the intent of ARCH 30001: Site Design (WIC) and ARCH 30101: Third Year Design Studio I. Each will inform and support the other. To begin, the first two weeks of the semester will be devoted to researching issues relevant to our site in Vermilion, Ohio, as determined by the Studio participants. The remainder of the semester will be dedicated to the development of a design also programmed by Studio participants. We will work in teams to accomplish both.

Nancy Rhoades and Madelyn Zaleski

Lake Erie Center For Marine Ecology and Conservation

Our Center for Marine Ecology developed into a non-building, a shell that envelops a whole community of life. Each integrated plant was chosen to play a specific purpose, which all connect back to protection and education. As more of a translucent shell around a whole ecosystem, this biosphere container mimics the flow of water down to the lake, meets the needs of its inhabitants by reacting kinetically to the surrounding environment, and gives back to our very own, Vermilion.

Rylie Schoch

Lake Erie Center For Lacustrine Ecology Conservation

The Lake Erie Center for Lacustrine Ecology Conservation invites people of any background to learn about and enjoy the many things Lake Erie has to offer. While it holds many things to explore and experience both inside and out, it sits modestly on the hillside hiding most of what it has to offer below ground. Using kinetics, the structure adapts to this ever-changing environment. By placing programs on the subterranean level, a different relationship to the lake can be gained and ecosystems can be brought closer for more in-depth observation. Water has also provided a new perspective connecting interior and exterior, upper and lower levels, and public and private programs through the aquarium. Whether someone is looking to expand their knowledge on Lake Erie ecosystems or simply grab lunch on the beach, the Lake Erie Center for Lacustrine Ecology Conservation provides a comfortable space to do so.

Ramzey Boukzam and Verity Green

Vermilion Oar

To sculpt a building on the lakefront of Vermillion, Ohio is to encapsulate the energy of the site and the livelihoods of the people to create a space that reflects the personality of Vermillion as a whole. The programmatic needs of the building strive to engulf themselves into the character of the landscape and create an environment where people can experience the Vermilion Oar: Observation, academics, recreation. Through these experiences, inhabitants are expunging the site’s potential and engaging in its ever-changing atmosphere. Using water as a design driver, the Vermilion Oar maximizes functionality without compromising the natural aesthetic of the existing site.

Professor Andrew Economos Miller

Architecture materializes the underlying assumptions of hegemonic social and political systems reinscribing its future inhabitants within the ideal lifestyles of its original producers. As suburbia spread across the world so too did its subjectivity, locking its inhabitants in carbon-intensive, commodity-dependent lifeways. This studio will engage directly with the material of canonical suburbs in order to “make room” for new unalienated subjectivities.

This studio focuses on the analysis and reposition of the quintessential American striated space: the suburb. Groups of two students will take a canonical American suburb as their quarry (pun intended) and work through two projects. First, they asked: how has the suburb organized the life of its inhabitants? How is private property inscribed in the land? And, how has the organization of domestic space produced or reinforced the division of domestic labor? This research re-orients the study of form from the divining of replicable techniques toward a dialectical opposition to the existing built environment.

Then, the students reposed the given material into new forms of living. How can what was once destructive become constructive of new lifeworlds? Their projects engaged with the material of the already-built as if it were the extractive field. The homes that are becoming the home that will be. Students will take their analysis of the original form as a doctor’s note through which to prescribe solutions and proposals for a future with communalized domestic labor, productive landscapes, and a meaningful engagement with the always-already contaminated earth.

Parker Zaras and Shazia Waggoner

Modified Celebration

Our project is located in Artisan Park, a small section of Celebration, Florida. Celebration has a majority white population, and the house facades reflect a racist past of plantation homes through the use of porches and columns. Our reconstruction demolishes the present site and reuses the same material, building something new from the rubble of the old. Once the houses were demolished, the foundation cavities were left open and used for water collection and fish farming ponds. Space for agriculture was also spread throughout the site. We placed the central community space at the southern part of the site to receive the most sun and encourage collectivity. The project also brings everyone together by pulling kitchen labor out of the family unit into collective spaces where labor can be shared, to produce a communal atmosphere by keeping everything as open as possible.

Sydney Karlock and Carly Preattle

Salvaged Suburbia

The idea behind Salvaged Suburbia was to create a community of spaces that emphasized interaction and provided opportunities for intimate gatherings and conversations while still having access to larger-scale endeavors. When designing these spaces we wanted to provide a legible structure for circulation and storage by repurposing the form of the previous homes, resulting in what we called frames. The frames were then embedded between spaces or along the outer edge of buildings. Salvaged Suburbia tackles the overuse of materials and furniture by creating collections of storage within frames to give new life to otherwise wasted items. Additionally, the tarping acts as a connection between outdoor space and the buildings to create a multi-use intermediate space for people within the town. Salvaged Suburbia is meant to build on the positives of suburban life while critiquing the negative aspects—like the gendered division of domestic labor—and giving new life to the previously used materials.

Logan Ali and Amy Li

Levittown After the Flood

This project directly engages with the material of Levittown in order to envision new forms of living. Following a critical analysis of Levittown, this design explores how what was once destructive can become constructive of new lifeworlds. Taking sea level rise of 1.5°C as a given, the project deconstructs Levittown and rebuilds itself within the finite quarry of deconstructed material. From the heap of crushed asphalt and vinyl siding arises a proposed cohousing community that seeks to address suburban ecology, climate change, prescriptive living, and domestic labor roles. This is manifested through the formation of three “islands,” or semi-autonomous architectural bodies that can exchange between each other and the outside world. Thus, a new form of living is created to withdraw from the conventional community of what was once Levittown.

Professor FrançoisSabourin

While architects accept that buildings have a limited lifespan, we generally assume the ground on which they sit to be immovable. Yet the landscapes and ecosystems we build in are under constant transformation, and in the anthropocene, the rate of change is accelerating. Our discipline’s assumptions about fixity in the face of instability contributes to the obsolescence of our buildings, with social and environmental consequences. This studio will explore how to build on unstable ground, making ideas

about change central to our design methods. Students will not only design an architectural project, but also the land on which it sits. We will choreograph the decadeslong evolution of the project's site and, over the course of the semester, speculate on alternative scenarios for both land and building. We will ponder how initial plans might take unexpected turns, and how our projects can adapt to new conditions. The value of the architectural proposals will not be in how tightly they fit a particular program or their immediate surroundings, but in the adaptive potential that they embody.

Justin Levelle and Dominic Holiday

Veil

The beginning of the project began with speculation on the future of our site, Kelleys Island Quarry in North Eastern Ohio. These speculations cover a wide range of site conditions including the quarry being used as a landfill (No Island), quarry being used as a golf course (Resort Island), or being used as a nature preserve (Green Island). With that being said, the structure designed must be adaptable to each of these speculations as these filling conditions will result in different boundary conditions with the building. The low-lying, long-span form allows for vulnerability between the filling process and the building itself. The façade of the building acts as a veil, meant to reveal and register the exterior geographical changes as well as the interior social/political changes. These changes could be the occupancy, the use of the area, or how the land enters the building.

Austin Bayer and Logan West

Displaced Ground

Our proposal to fill the Quarry on Kelleys island begins with a projection of two overlapping grids. What we get as a result of the second grid imposing on the first is a figural displacement that ultimately becomes the building project in each of our three scenarios. The building project is organized through a subdivided version of the secondary grid that is projected to the site. A similar figure is produced in the building plan that is marked by black poche. The figure in this context contains crucial elements such as mechanical systems, restrooms, and circulation. White poche marks partitions, or space that is adaptable to new conditions. Soldier pile walls coupled with cross lot struts were used to allow for the project to operate well in the buried condition as well as the non-buried condition. “Displaced Ground” is an intuitive and speculative model for designing on unstable ground.