Professor Charles Frederick

Parks, open spaces, and public areas are essential in the overall framework of a community. Early American settlement patterns were centered upon a public area – the commons – where the community could gather for important events; training for the local militia; and sharing for animal grazing. Often important buildings – churches, schools, and town halls – were located directly adjacent to these places. As many communities matured, they located important memorials so that community’s members would always remember their past. American landscape architecture traces its history back to Central Park and Frederick Law Olmstead’s first use of the title of our profession – landscape architect. The profession would get its start with the building of a great public park for a great city. It was the physical character of the park as well as the fundamental concepts of ecological services and social interactions. These are still design goals for public spaces today. A public space, park, or square should define the community – it is where the public comes together to celebrate; to articulate its values; and provides intrinsic social and ecology services. This studio explores the neighborhoods in Cleveland’s eastside and investigates various types, scales, and functions of public spaces. It includes existing places and places that have an opportunity to provide a different role for the community. The design processes researchs and employ strategies from the Cleveland Tree Plan with a focus on the structure, function, and role of the urban forest as it relates to climate change and community resiliency.

Morgan Mackey

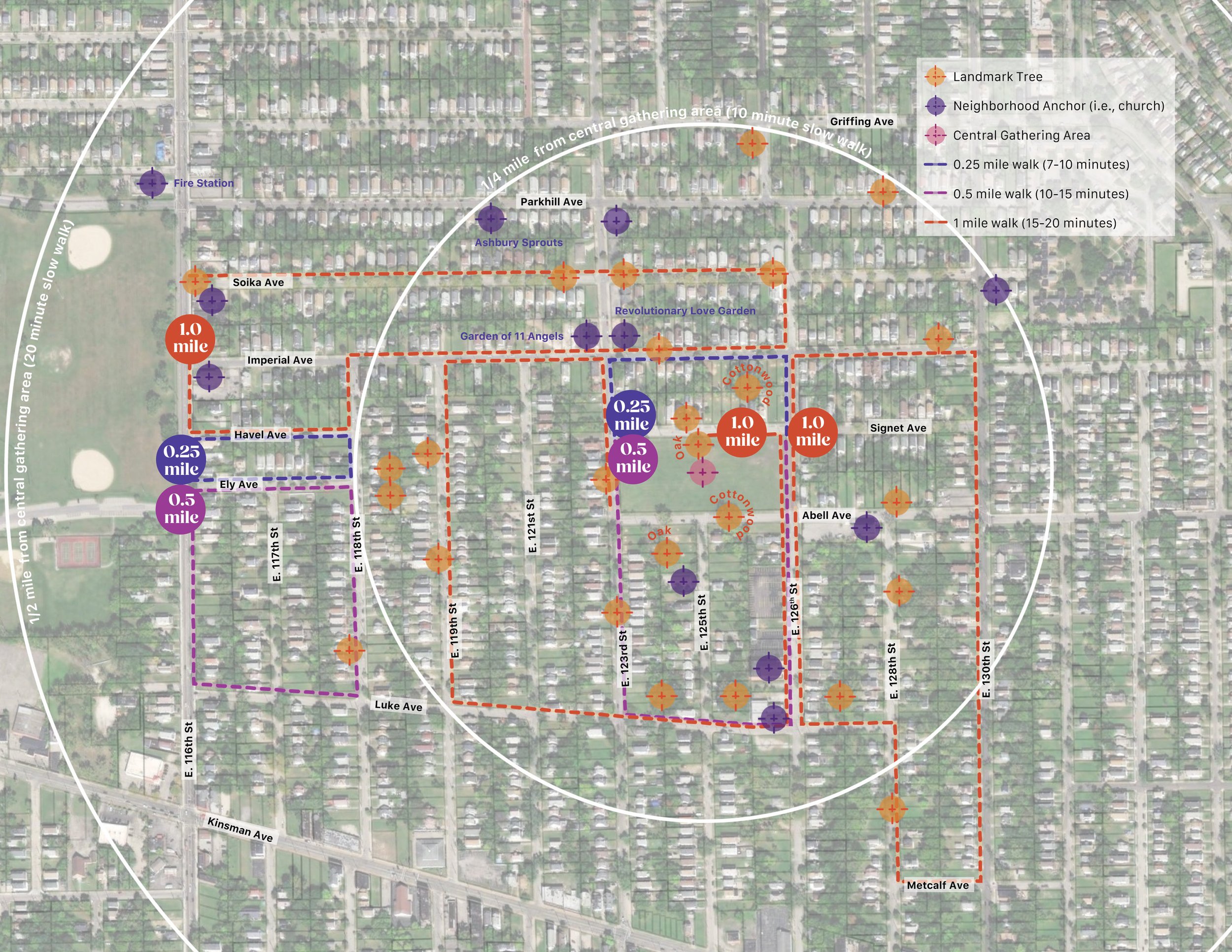

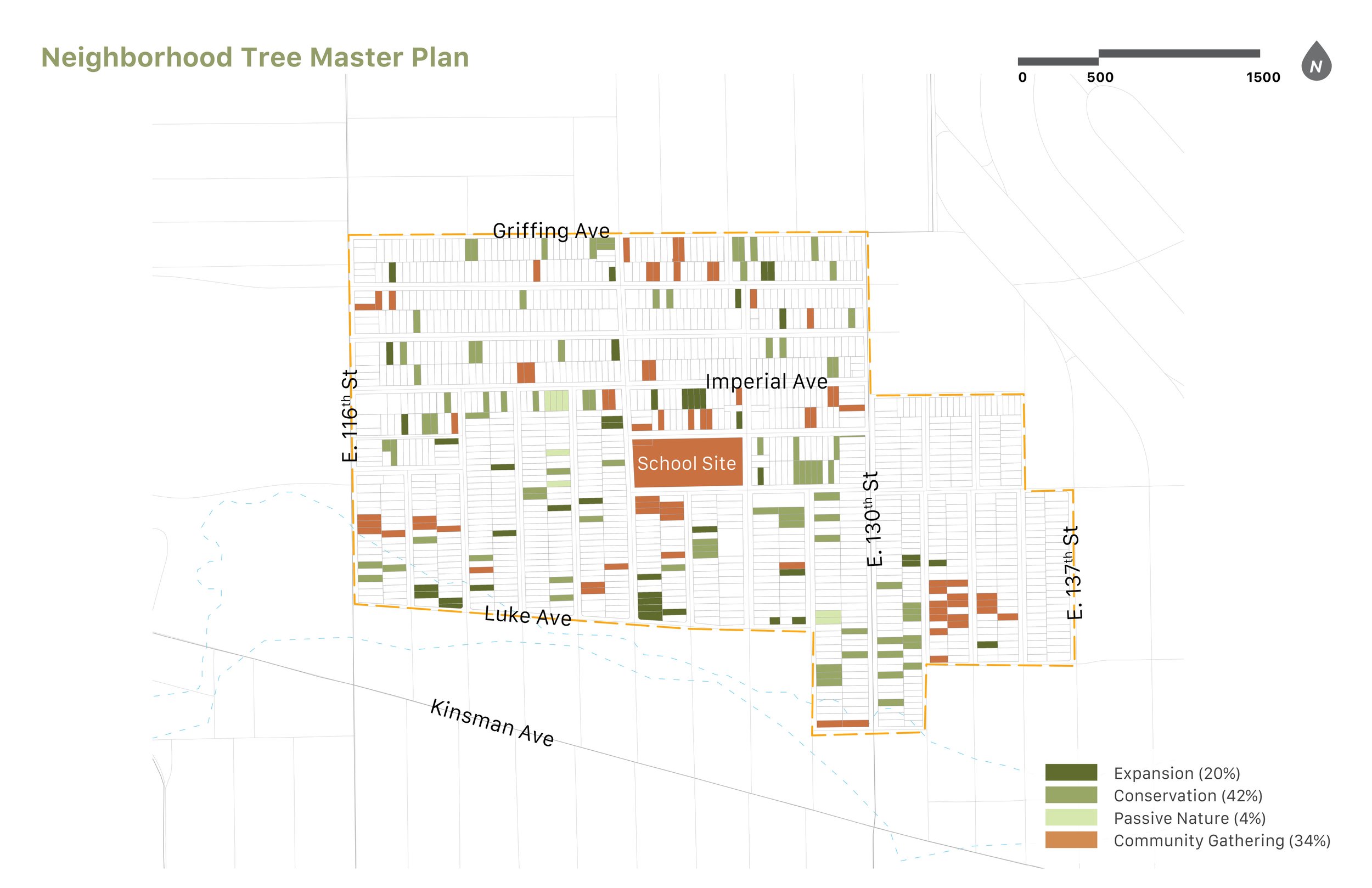

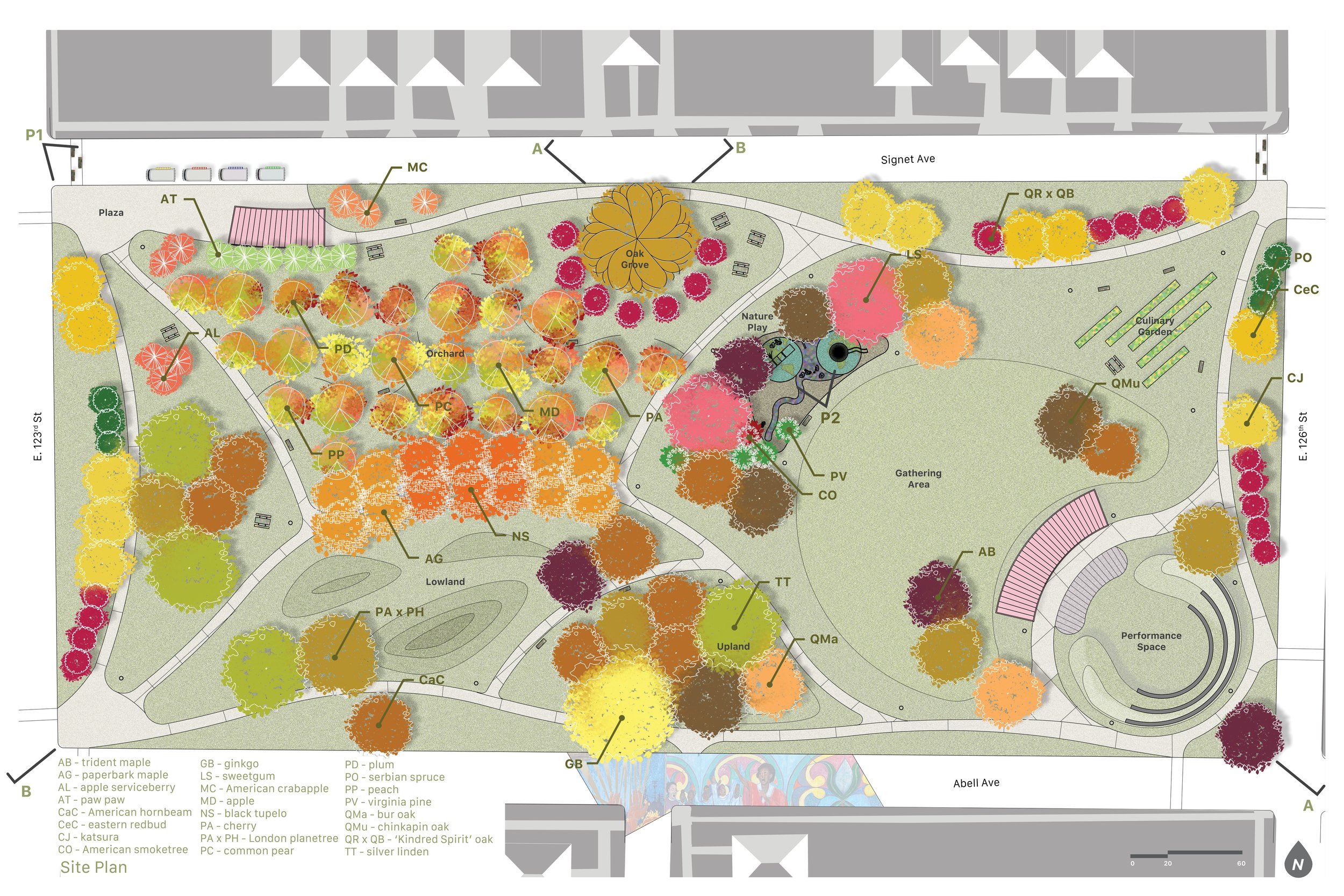

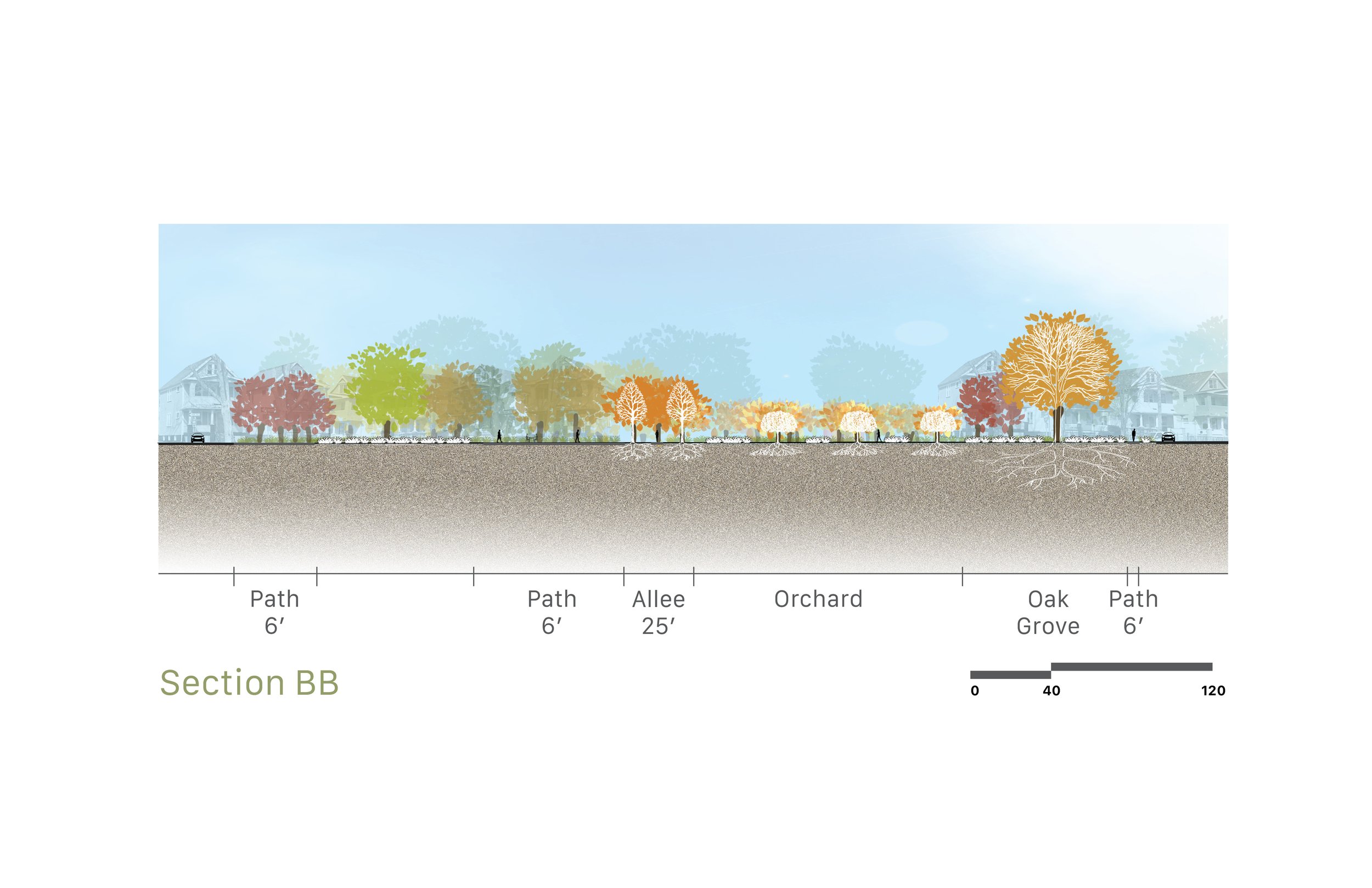

Tree Stories: Community-Driven Design to Expand Cleveland's Urban Tree Canopy

While efforts are underway to restore Cleveland to its status as “The Forest City”, including regular updates to the Cleveland Tree Plan and the revival of Cleveland’s Urban Forestry Commission, sustainable, equitable change requires a network of neighborhood forestry strategies. Trees contribute to a high quality of life for residents by encouraging healthy outdoor lifestyles, decreasing the urban heat island, reducing the likelihood of crime, and increasing nearby property values. The Buckeye-Kinsman neighborhood is an important link in Cleveland’s urban forest and can expand its tree benefits through the utilization of vacant lots. Historically, the neighborhood was anchored by churches and schools that served the area’s high population density, which has since declined by over half. The site of Lafayette School, once an important central gathering area and now a grassy lot, presents the opportunity to create a new community space and expand the urban tree canopy. The site can also anchor a network of active, passive, and natural lots that protect the existing tree canopy and better serve community members. A “Neighborhood Tree Walk” encourages pedestrians to explore the area along pre-determined routes, starting at either the school site or Luke Easter Park and learning about important trees. The central gathering area can host food truck events and performances as well as daily activities with an orchard, gardens, and playground. Developed based on findings from community members, the concept builds on the neighborhood’s history, increases the benefits of urban trees, and brings life back to a historic community space.

Professor Cat Marshall

THE CITY THE BLOCK THE GARDEN this Index Studio asks, can Cleveland and Querétaro catalyze the transformative momentum of its peri-urban landscapes to achieve hydrological autonomy? How can landscape, architecture, and urban design enhance the metabolic cycle of resources? How can design address closed, independent systems of water management that eliminates waste? This studio approaches water circularity by envisioning new hydrologically autonomous models for urban redevelopment in the urban periphery of Querétaro and Cleveland. The students identified vulnerable areas of water in Cleveland Ohio or on a comparable site in Querétaro Mexico. Proposals identify spatial and infrastructural strategies for achieving feasible, autonomous, and equitable water cycles of their respective city with resilient design propositions that builds capacity for water equity across many layers of society. Using a strong concept, design proposals are manifested at the city, block and the garden scale. The concept is derived or responds to the landscapes existing conditions, the sites cultural significance, meaning and experiential qualities. Each student designed a series of distinct schemes that demonstrate an understanding of the environmental and aesthetic importance of water for your city and why the proposal is a viable solution. Building in flexibility of open, inclusive and varied experiences. The first half of the studio translated sites in risk through a detailed summation catalog of the use of water and the cities development. Followed by classifying existing typologies of water in the landscape to define scope of each student’s project. The second half of the studio defined a narrative of water logic in site transformation and provided water autonomy through comprehensive set of deliverables.

Jody Lathwell

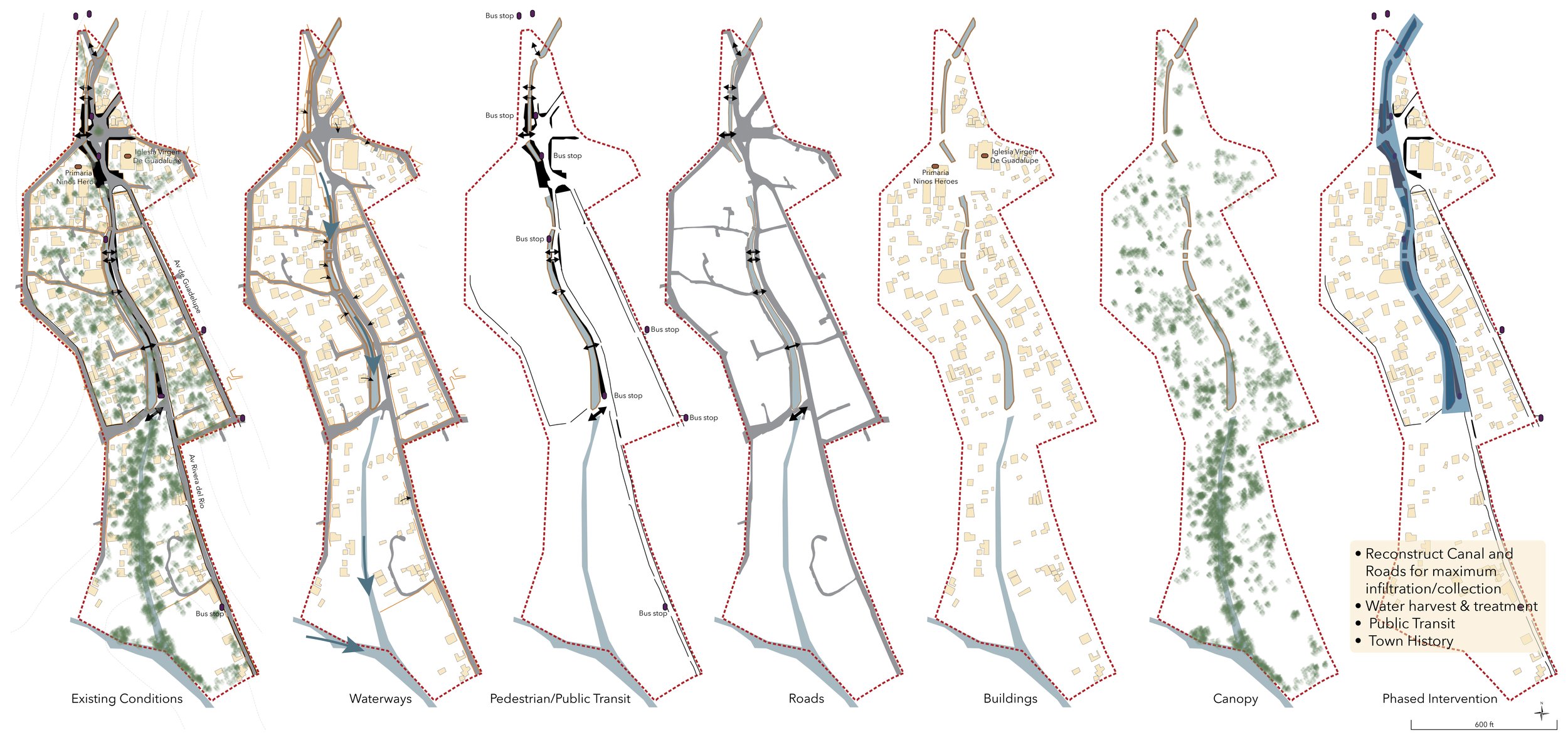

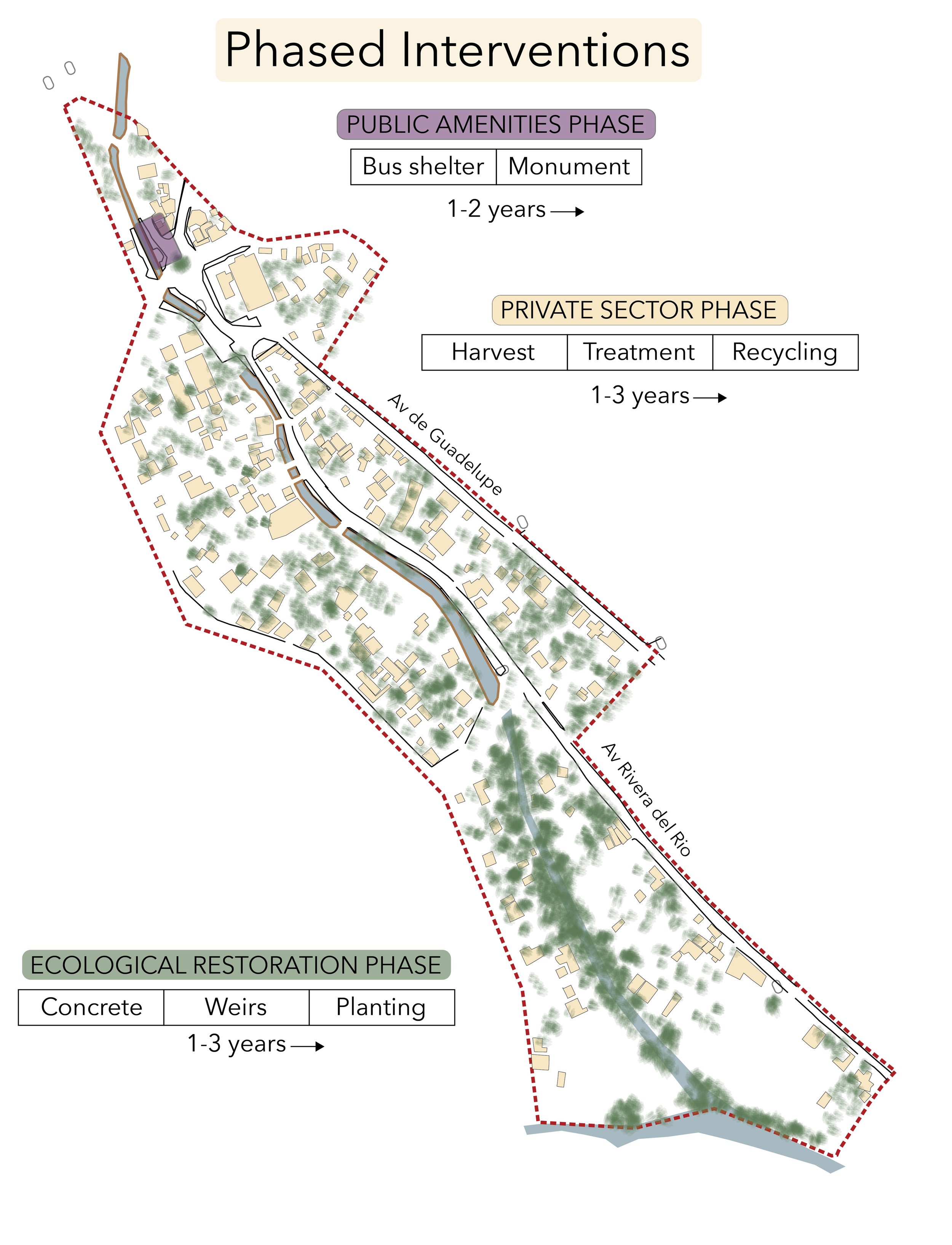

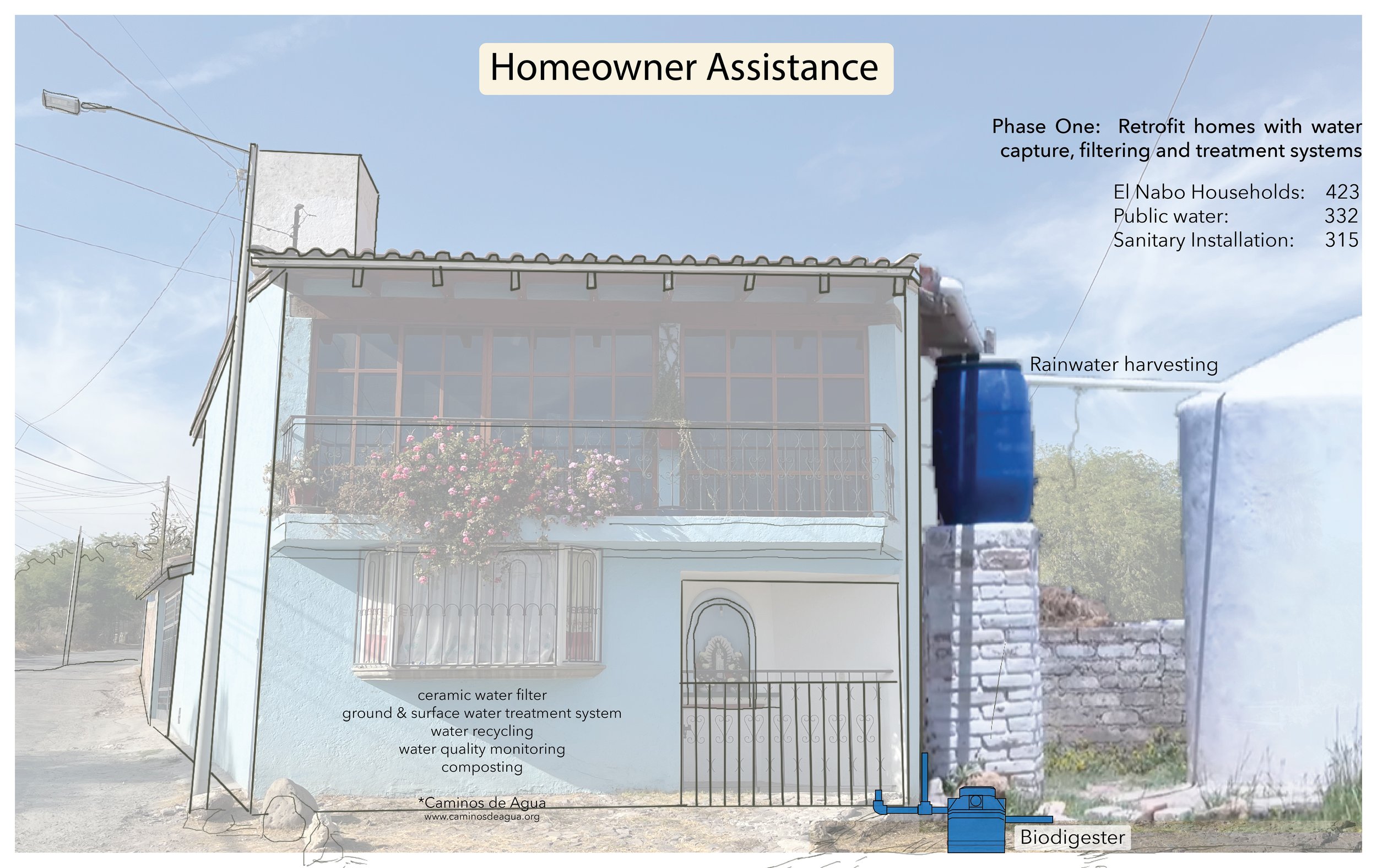

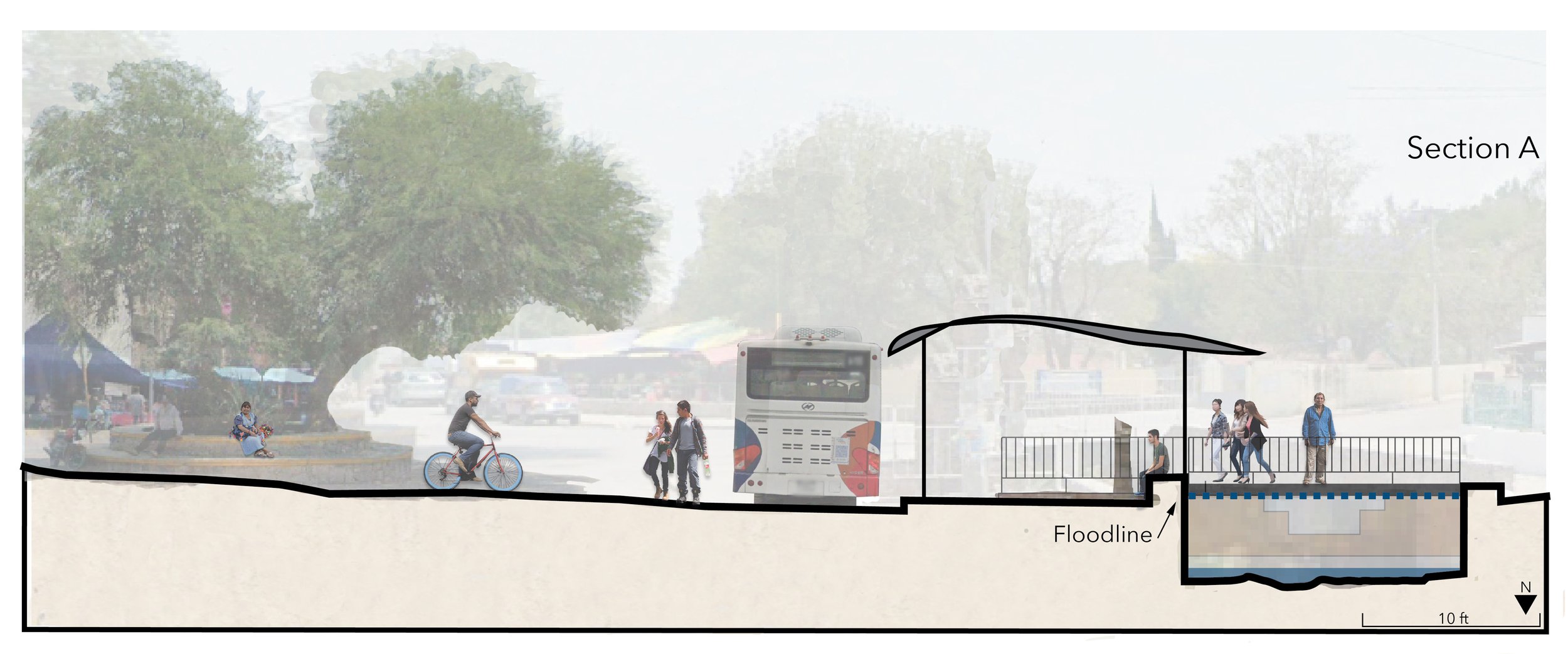

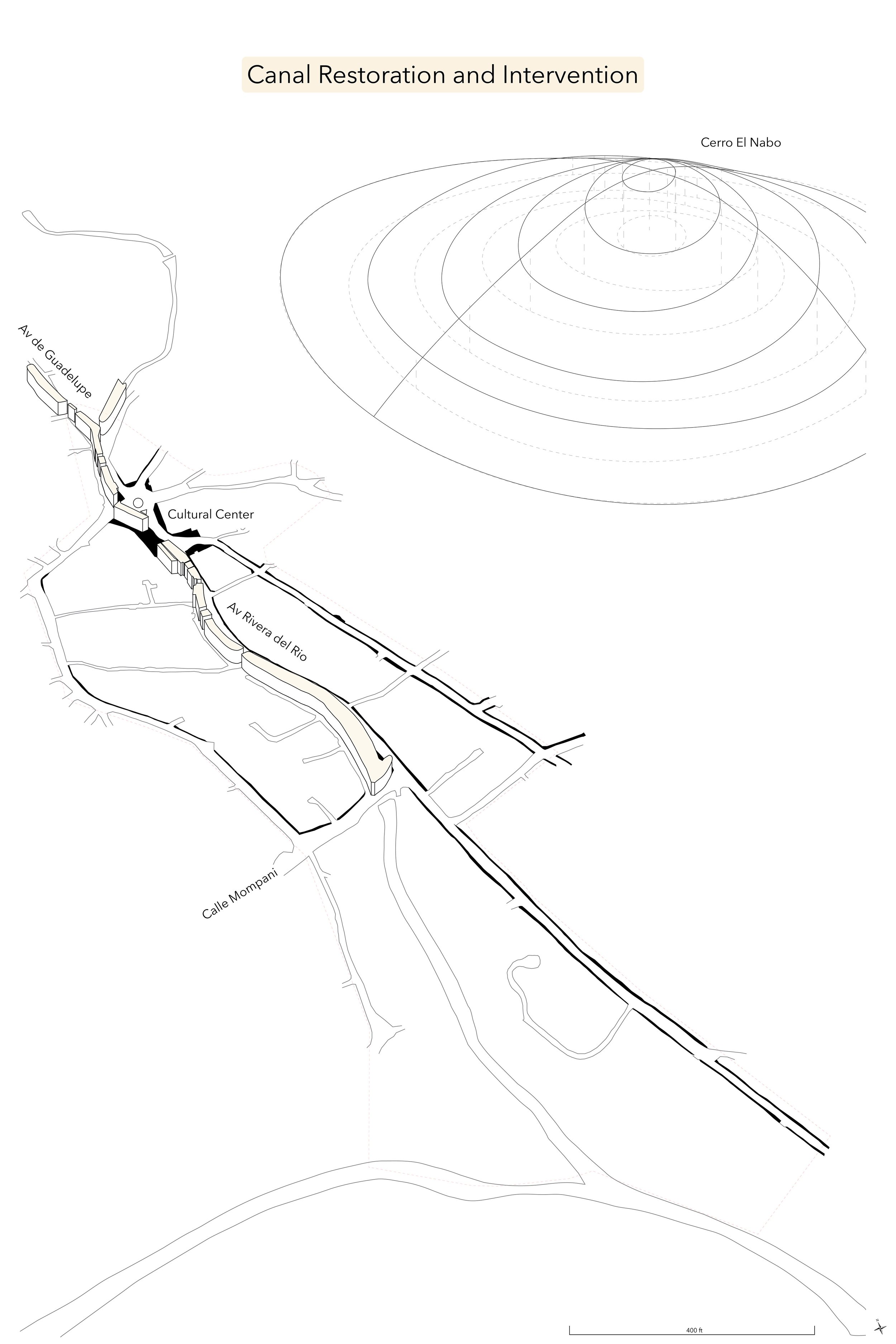

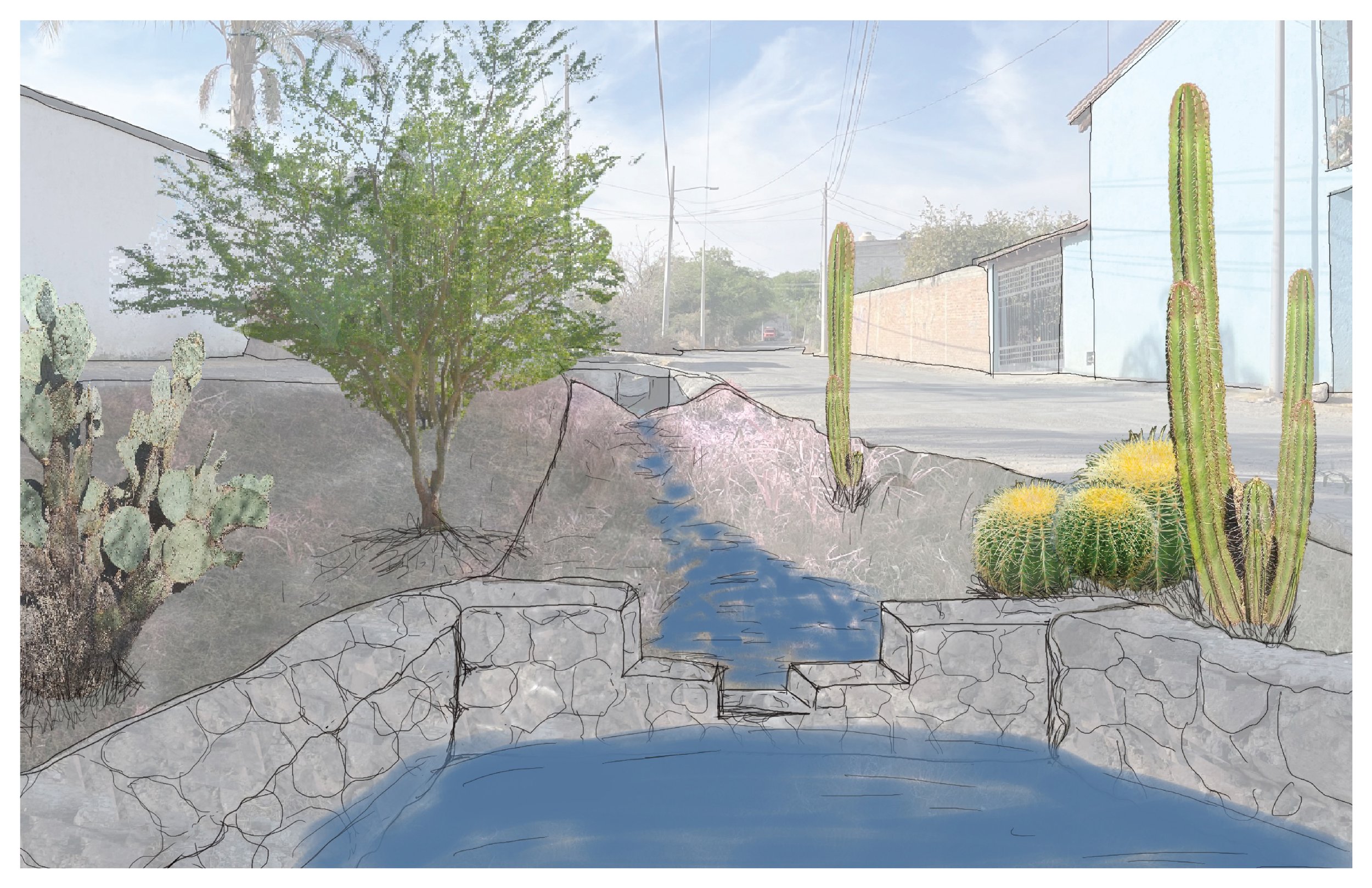

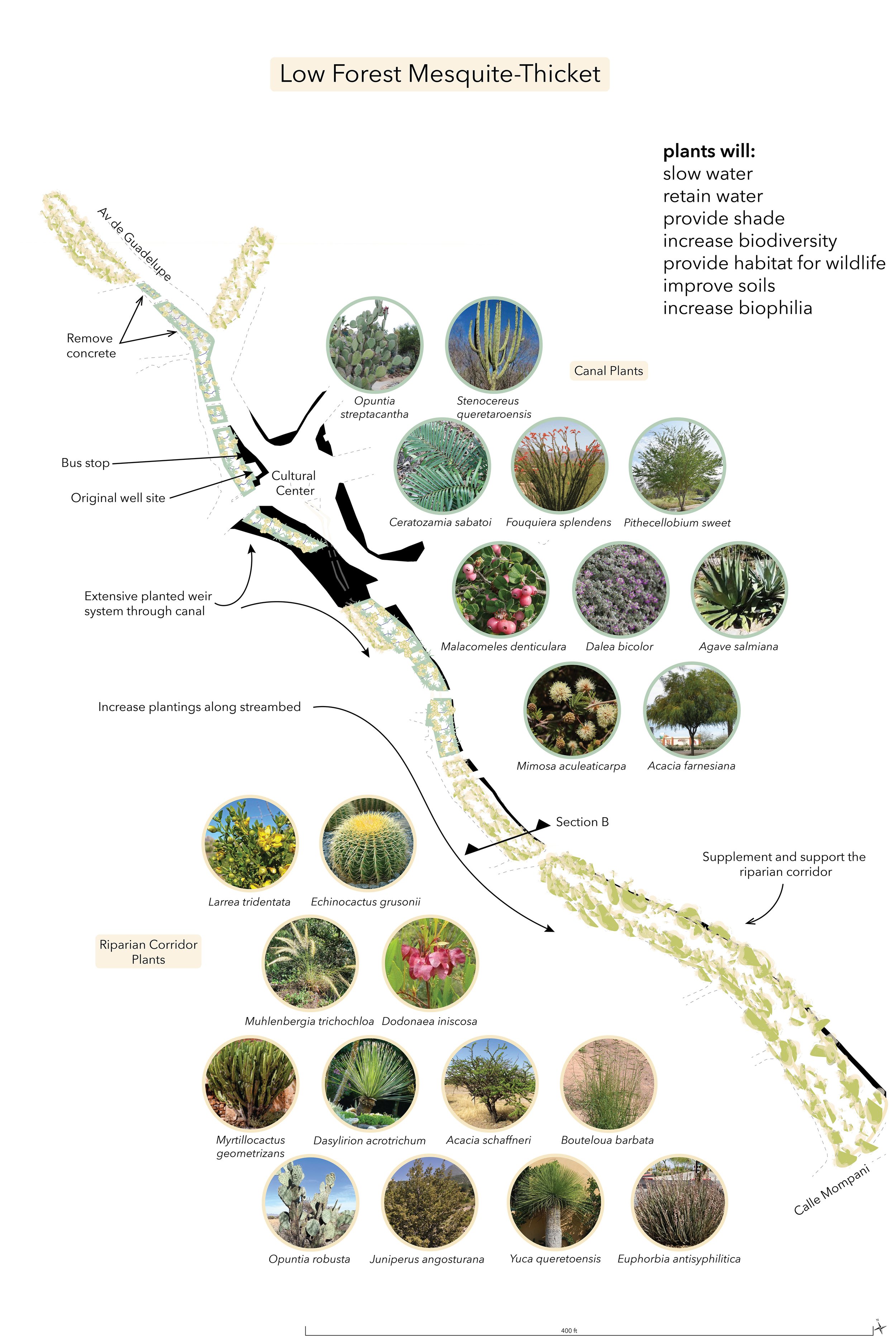

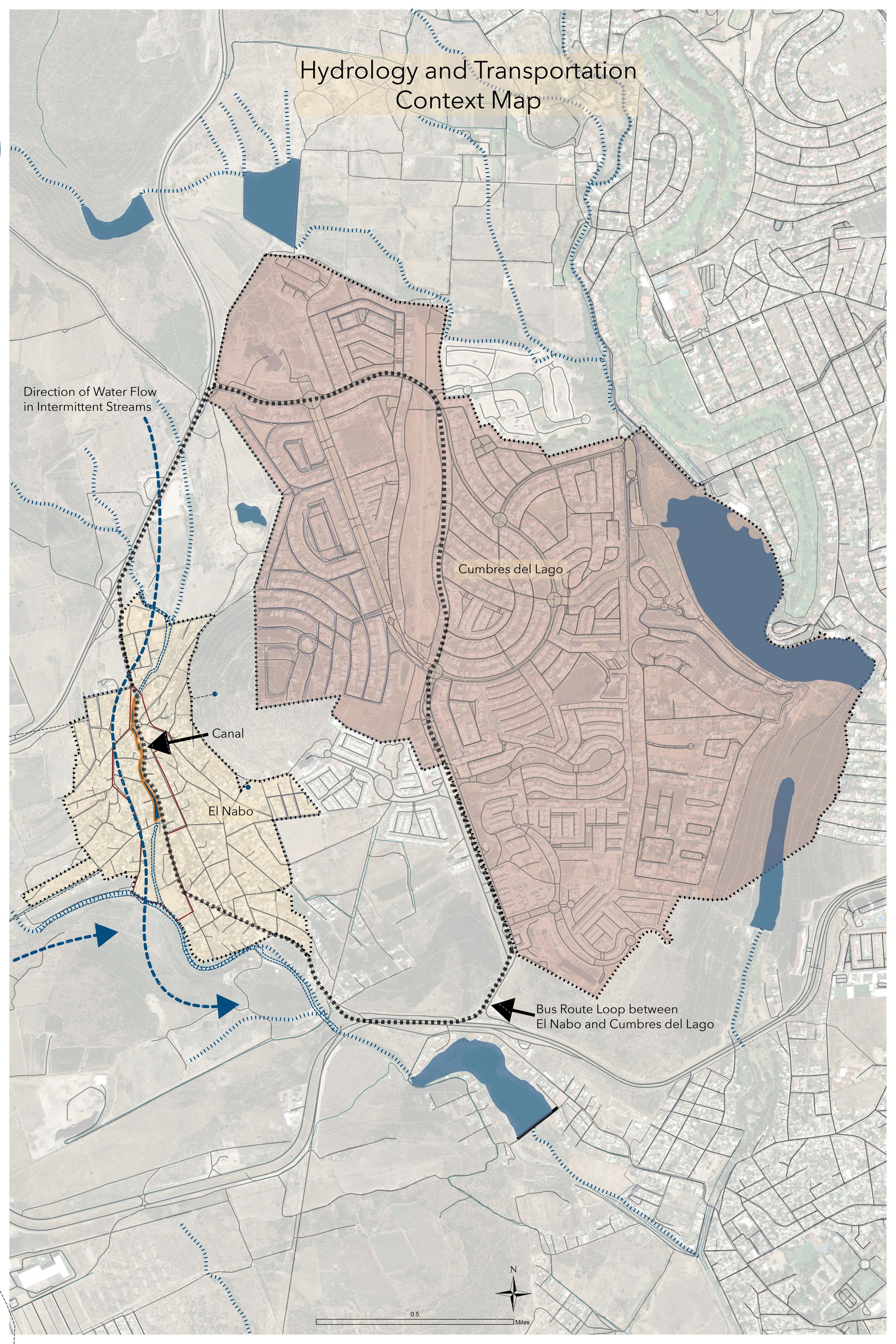

El Nabo: Designing Water Infrastructure and Implementing Natured-Based Solutions

Located in Central Mexico, El Nabo is a traditional neighborhood in the northern part of the municipality of Querétaro. Water issues in the Global South have become increasingly severe and many people do not have access to a clean and reliable water source. As the population in Querétaro increases at a rapid rate, private development, industry and agriculture have increased demand on the water supply. This growth has come at the expense of towns like El Nabo, which was settled along a stream that can no longer supply the town with water. In addition, the entire region, which is in El Bajio, the lowland, has been experiencing increasingly severe flooding because of rapid urbanization and climate change. Working at a local level, this intervention works in multiple ways. This project suggests retrofitting all households and buildings within El Nabo with water harvesting, purification and treatment equipment. Treated water would then be recycled and used in home gardens. In addition, a complete overhaul of the canal system that runs through the center of town will work to slow and capture water during flood events. Adding weirs along with extensive planting of native plants along the canal and stream will also slow, filter and increase water infiltration into the soils. The plantings will also enhance life for residents, increase wildlife habitat and reduce the negative impacts of the urban environment. Using nature-based solutions works to build up green infrastructure that directly impacts water access and quality.

Asmita Dahal

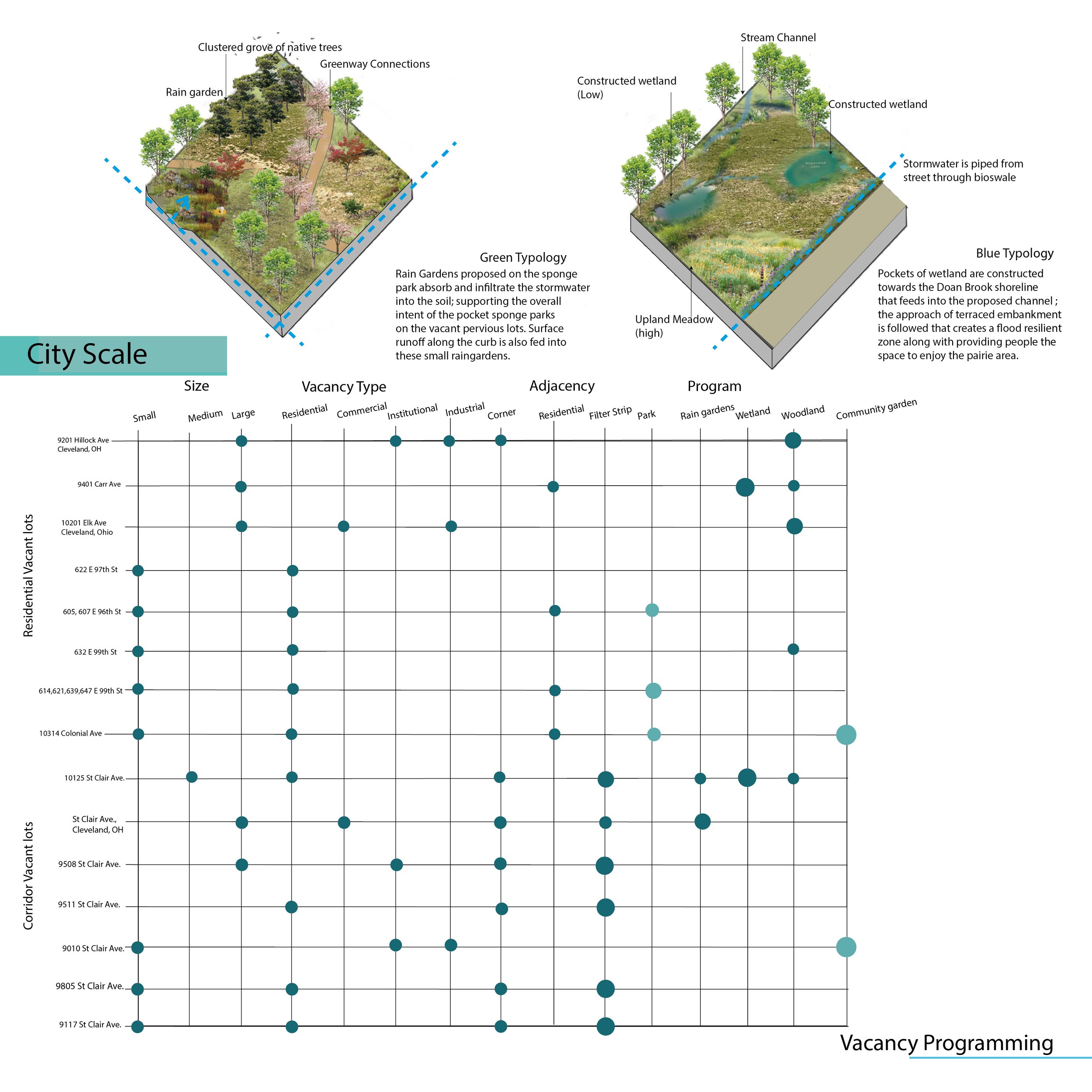

Urban Voids as Stormwater Assets in Glenville

Cleveland receives an average of 38” of rain annually, and much of this volume arrives in the form of downpours and rainstorms that run into the city's combined sewer. On heavy rainstorm events, it overwhelms the drainage system and hence drains into the Combined sewer overflows around the city that eventually goes into Lake Erie. Glenville, lying on the Doan brook watershed on the eastern side of Cleveland, has been recognized as a socially and environmentally vulnerable neighborhood with the population declining over decades and lack of community spaces, the cultural identity of the neighborhood is also at stake. The project aims to address these challenges by introducing green infrastructure solutions that focus on capturing and retaining stormwater on the landscape, while also creating community spaces and enhancing biodiversity. The project includes several components, each designed to achieve one or more of the project goals: Vacant lots: The project identifies multi-pilot sites in the community voids, including filter strips, parks, rain gardens, wetland and woodland areas. The variations in these lots result in variation of the amount of the water they hold. Road corridors: The project includes grass filter strips that are targeted on undeveloped/unpaved areas that will be seeded with native wildflowers. Water from the roads and sidewalk flows into these filter strips. After absorption, the remaining water sieves into the native meadow ground stabilizing the water table below and reducing subsidence. Wetland treatment park: This 1.8-acre empty tract of land in the neighborhood is re-engineered as a catchment for stormwater and a public green space. Stormwater from nearby streets and neighborhoods is conveyed into the wetland basin, which removes the water, at least temporarily, from the city’s drainage system and adds capacity to the system during heavy rainfall events. The wetland design and vegetation create habitat for birds and butterflies, while vegetated plantings help filter the captured water. The outflow is sized for 100-year storm retention for 12 hours. Linear Park/greenway trail: A mile-long linear park/greenway trail is connected to the wetland treatment park through the proposed central park of the neighborhood. Wetland edges with the neighborhood are defined with evergreen hedges and an interactive walkway with an unobstructed view of wetland is created within, which eventually links into Rockefeller Park.