Charles Frederick

This studio explores the neighborhoods in Cleveland’s eastside and investigates various types, scales, and functions of public spaces. It includes existing places and places that have an opportunity to provide a different role for the community. The design process will research and employ strategies from the Cleveland Tree Plan with a focus on the structure, function, and role of the urban forest as it relates to climate change and community resiliency with the consideration of the needs of a community stakeholder.

Shristi Bhandari

The Green Oasis

The green oasis mainly explains the pocket of spaces that are formed in the design. Each oasis carries its own significance and function. The design approach prioritizes a harmonious integration with the natural landscape, thoughtfully considering the existing topography to create a seamless fusion of built and natural environments. By building upon the site's inherent features and leveraging its unique characteristics, the design aims to craft a cohesive and sustainable urban ecosystem that not only promotes environmental stewardship but also fosters a profound sense of well-being and connection among residents. Through the intentional integration of nature, art, and community, this project seeks to create a vibrant and inclusive public space that cultivates social cohesion, inspires community engagement, and serves as a model for sustainable urban development.

Cat Marshall

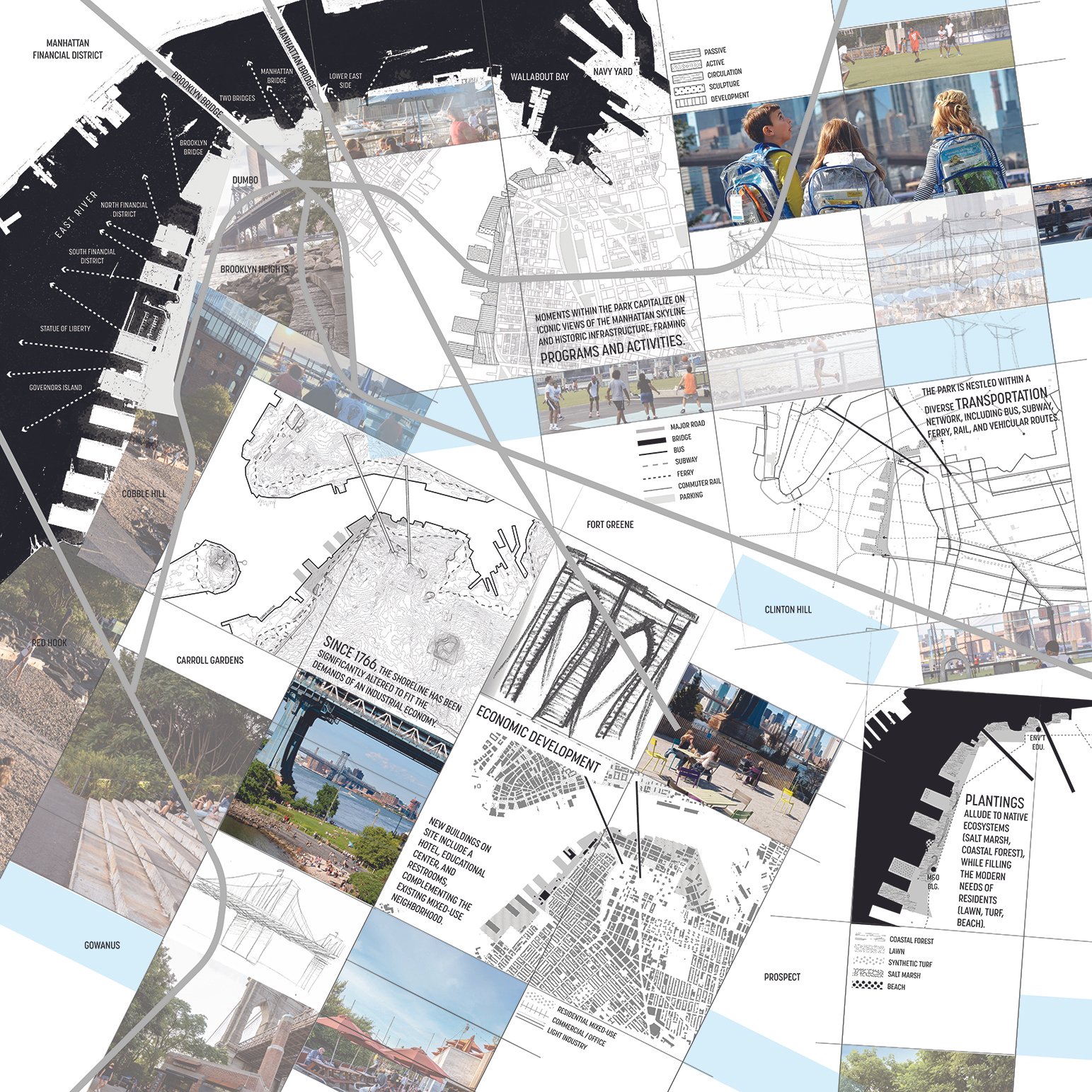

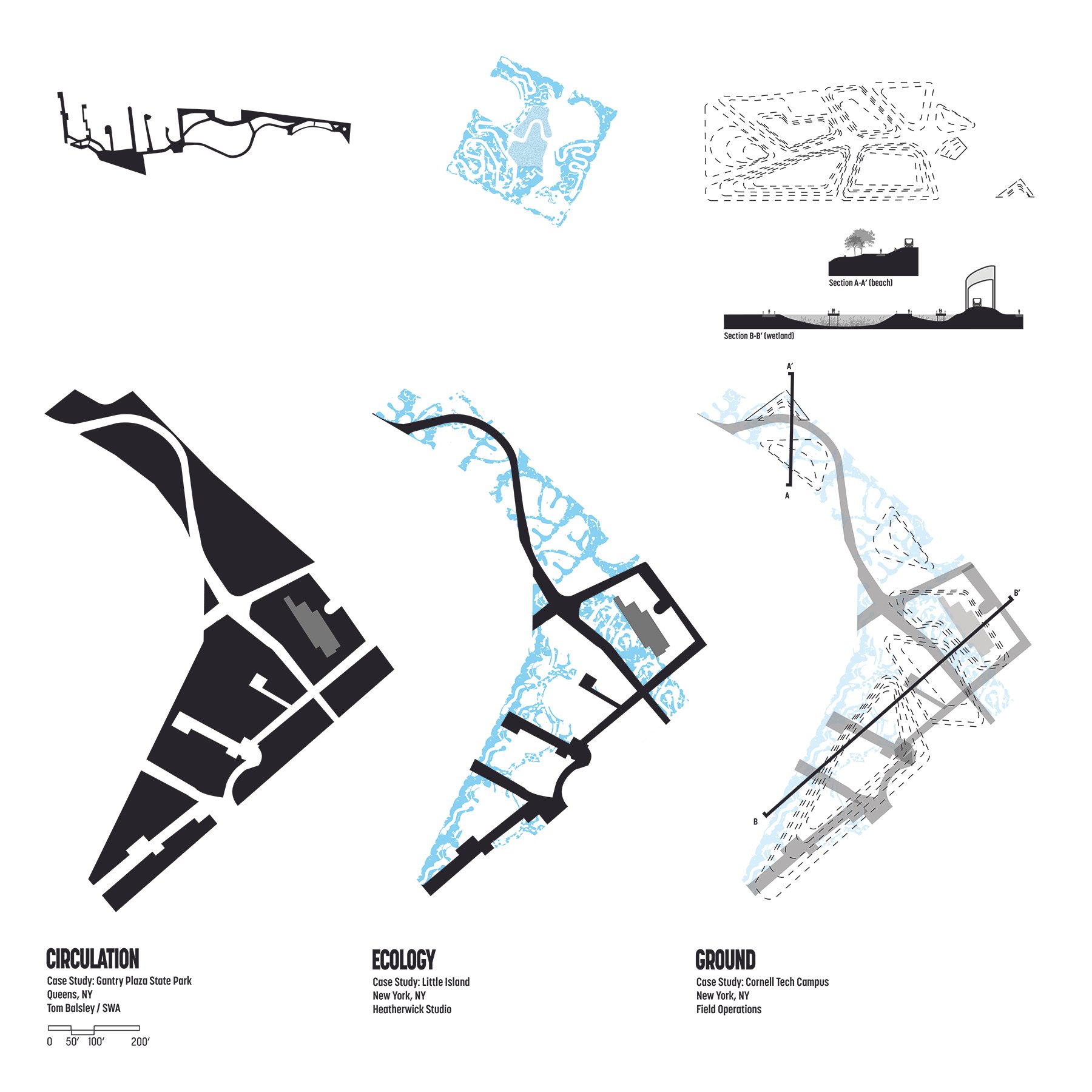

Cleveland’s long history of public spaces and current large scale waterfront infrastructure design need stronger connections back to the city urban spaces and gardens. Exploring how public space provide both ecologic activity and amusement. The studio is looking at two sites that are currently underutilized and house existing stormwater infrastructure (CSOs and pump stations) the students are asked to think of Greener solutions to the problem of abundant water.

Stormwater and flooding will continue to be an environmental concern to Cleveland if nothing changes. Over the last decade the City of Cleveland has been updating its combined water and sewer infrastructure but needs to consider green(er) infrastructure to accommodate the increase of rainfall that is predicted. Research has shown that precipitation has increased by 11% and heavy storm precipitation has increased 37% since the 1970s. The city experiences about 155 days of rainfall annually.

Settlers Landing, Cleveland, Ohio. An urbanized river bend and adjacent lands on the margins of The Flats neighborhoods in Cleveland Ohio. An existing park in the fringes of vibrant communities and redevelopment projects; is adjacent to the Canal Basin Park and to extensive transportation infrastructure that connects the flats to Cleveland with the RTA station and the Detroit Superior Bridge, west of Terminal Tower and Tower City.

Morgan Mackey

One Minute of Patience

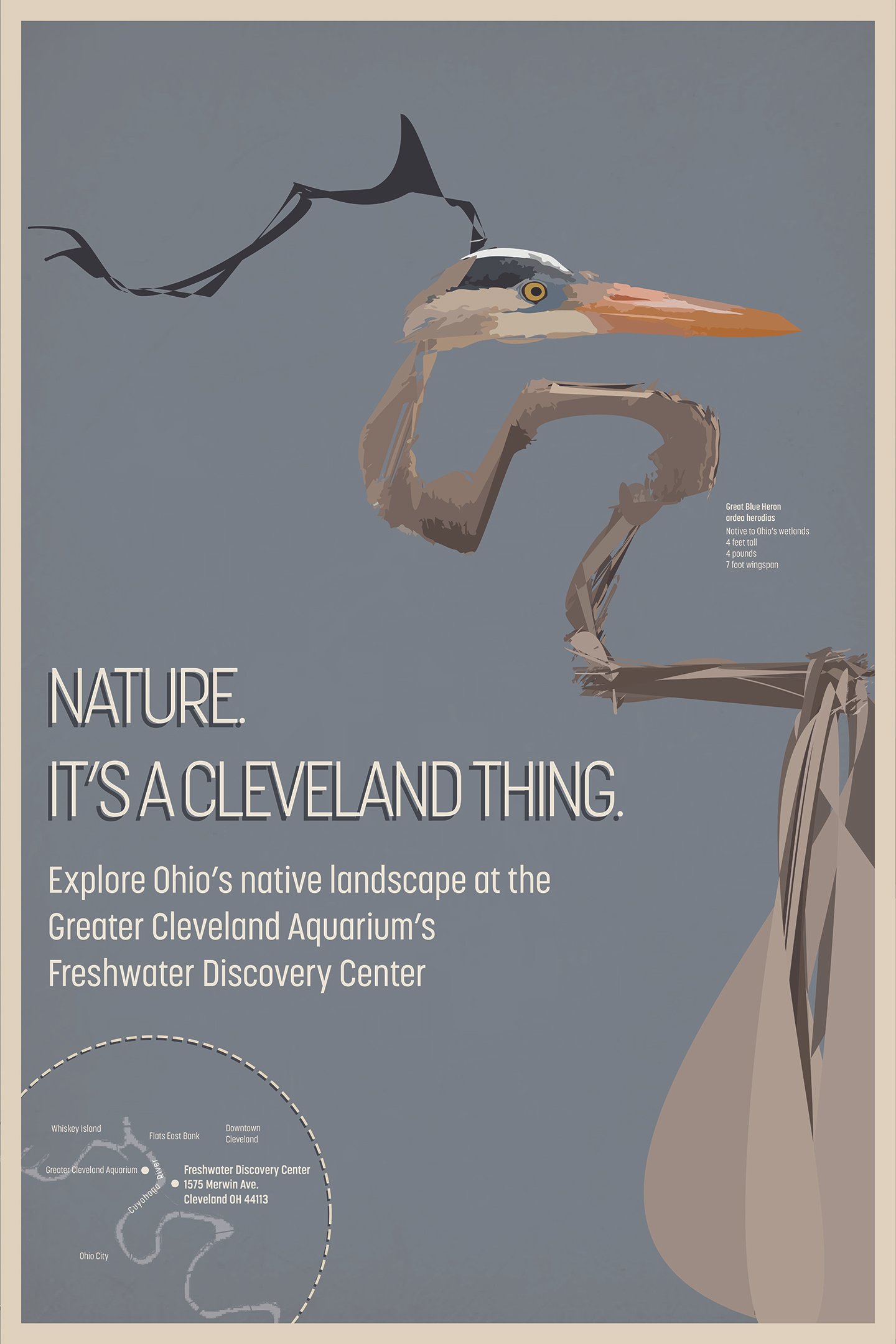

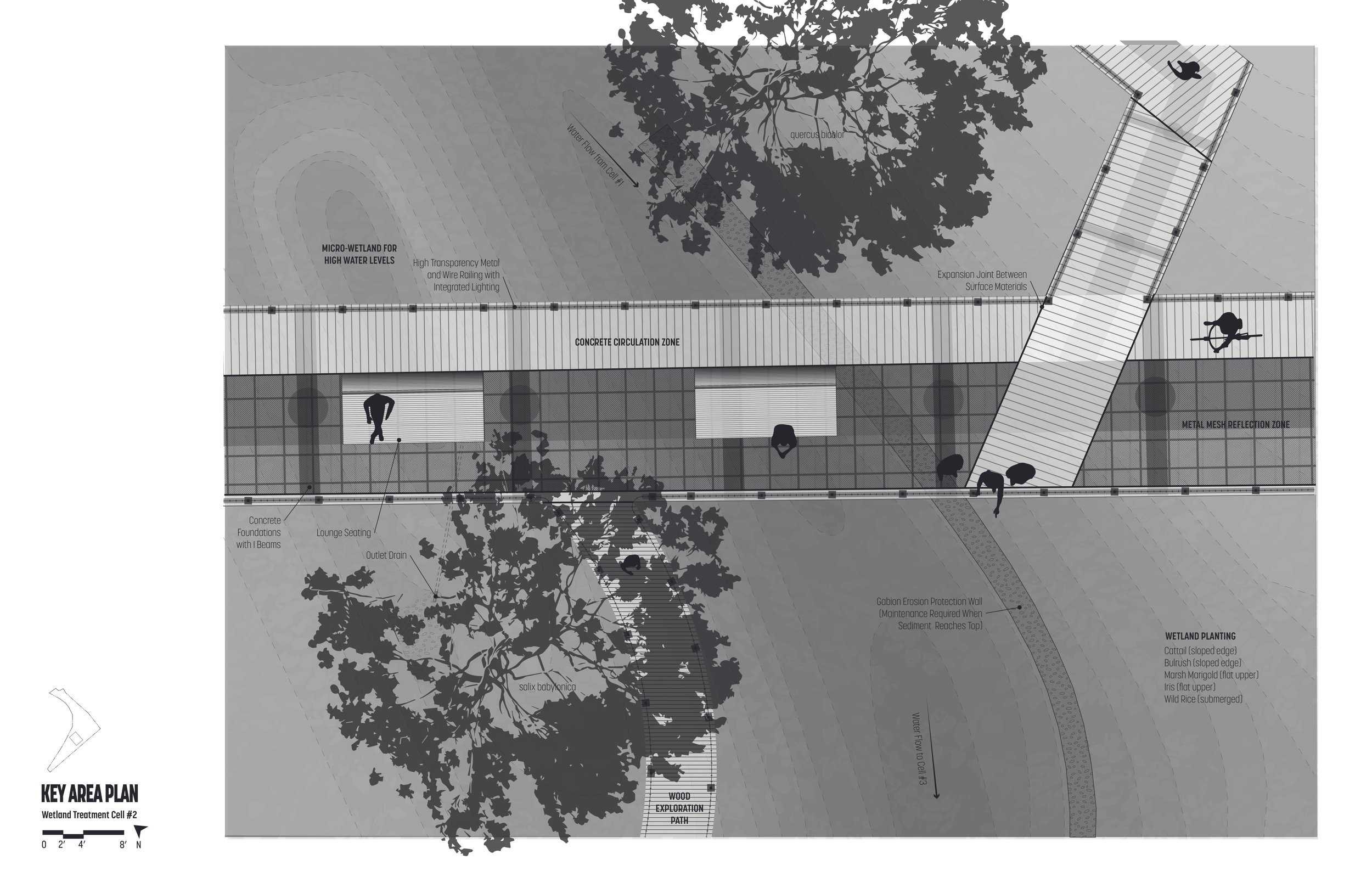

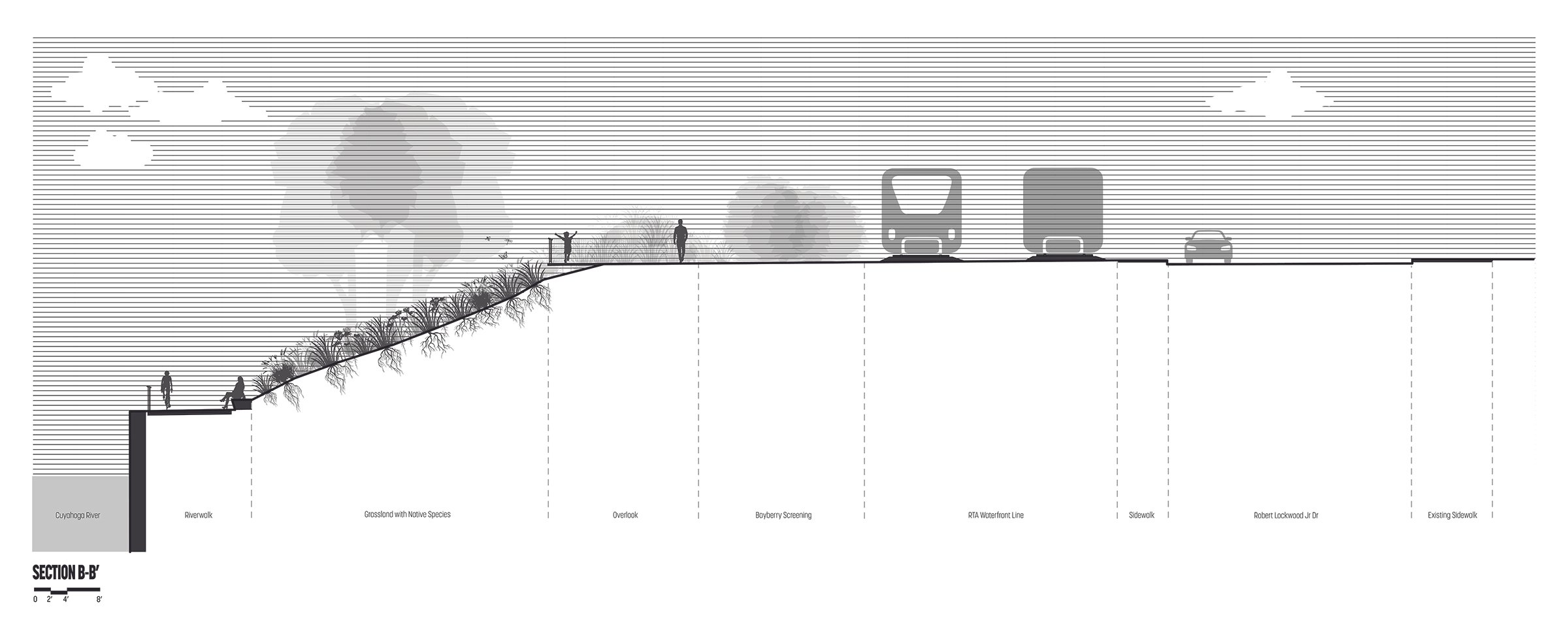

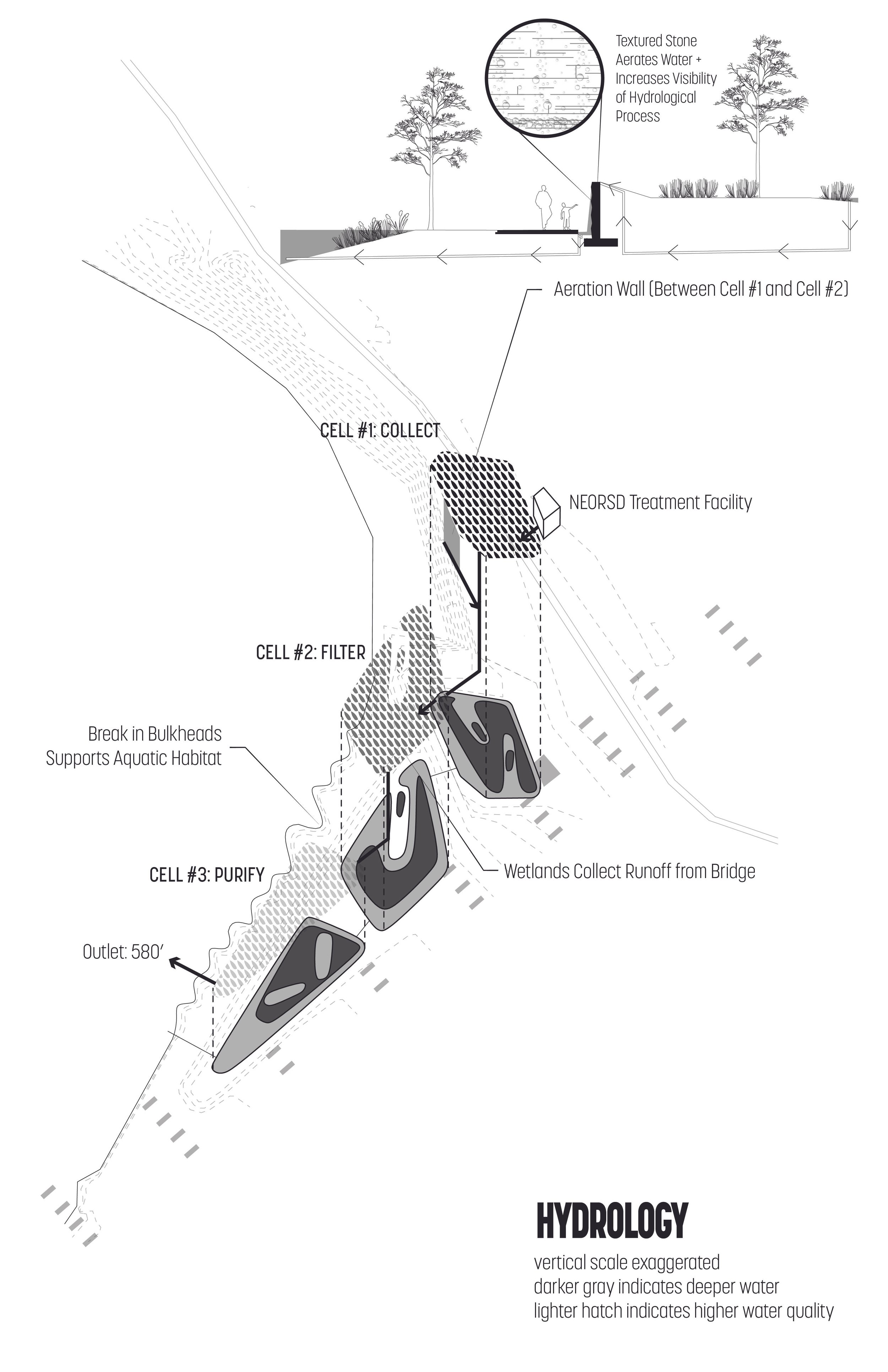

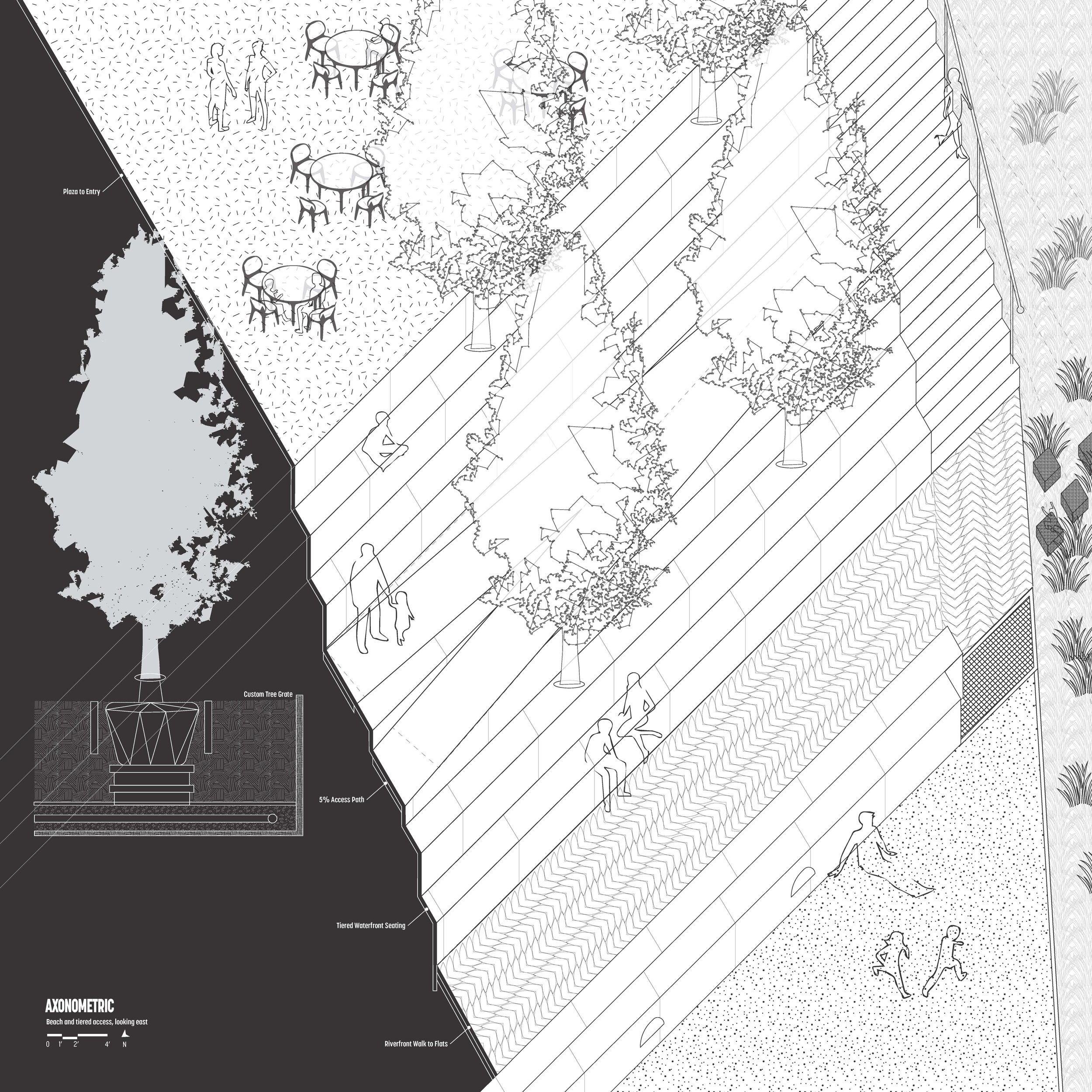

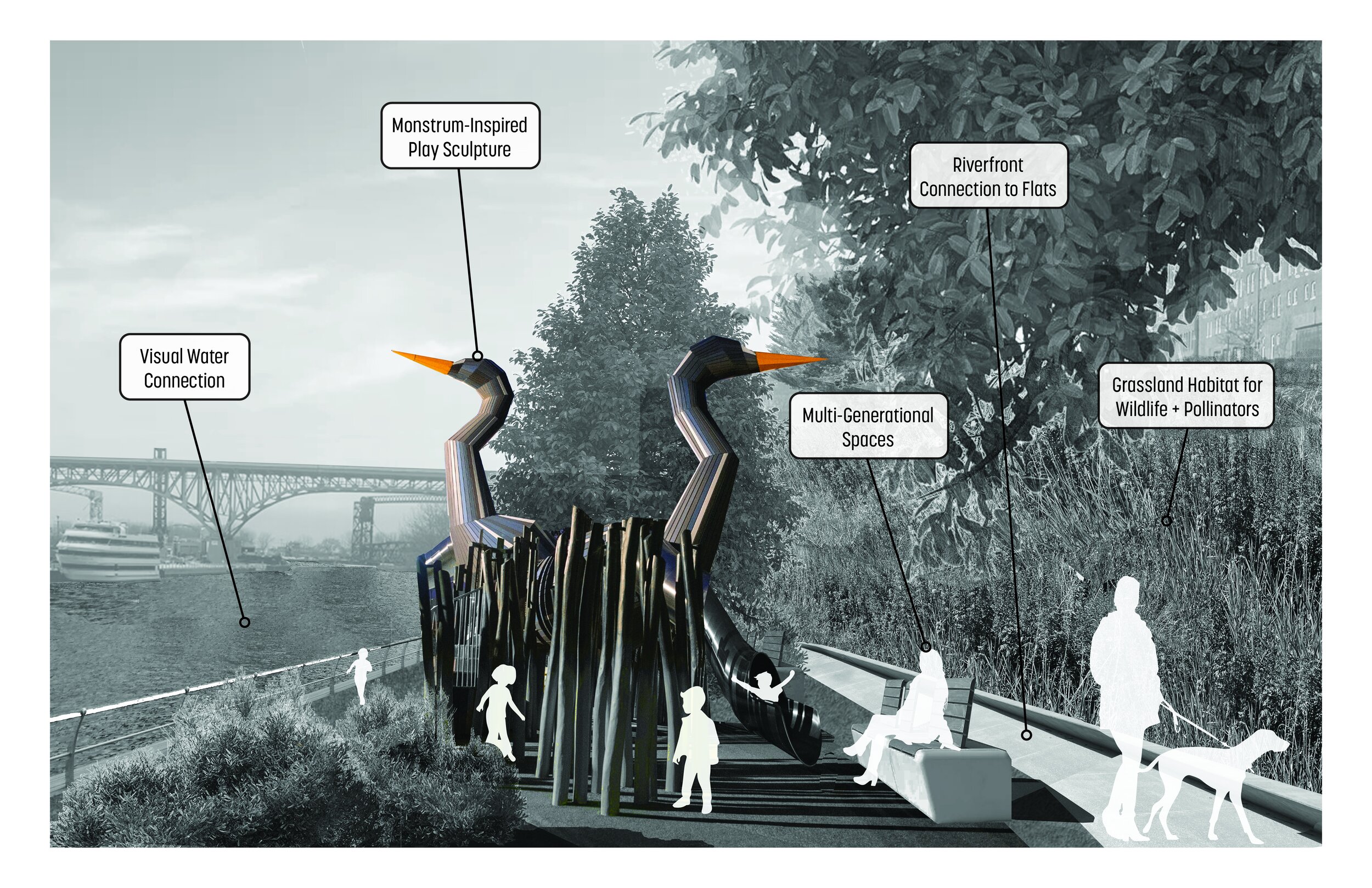

The Ancient Greek proverb states, “One minute of patience, ten years of peace”, emphasizing careful consideration over hasty action. The proposed design for Settlers Landing is an example of how thoughtful design can sustain future generations. To mitigate the effects of existing combined sewer overflow, the design proposes three wetland treatment cells that cleanse water by collecting sediment and absorbing toxins. A boardwalk features opportunities for water education with outdoor classrooms and connects to the Freshwater Discovery Center, RTA Waterfront Line Station. In front of the Center, a flexible gathering plaza supports events and casual use. Tiered steps bring visitors closer to the river, ending in a beach for fun summer activities. The adjacent playground highlights the native Great Blue Heron, a symbol of patience and resilience. A riverwalk connects the site north to the Flats, running alongside grassland that supports local pollinators and wildlife. As a secondary option, visitors can move through the grasses on the exploration path, ending at an observation deck and hill that overlooks the site and its surroundings. The design’s ecologically sensitive engineering and multigenerational spaces ensure Settlers Landing contributes to a healthy future for all.

Cole Sukys

Turning Point

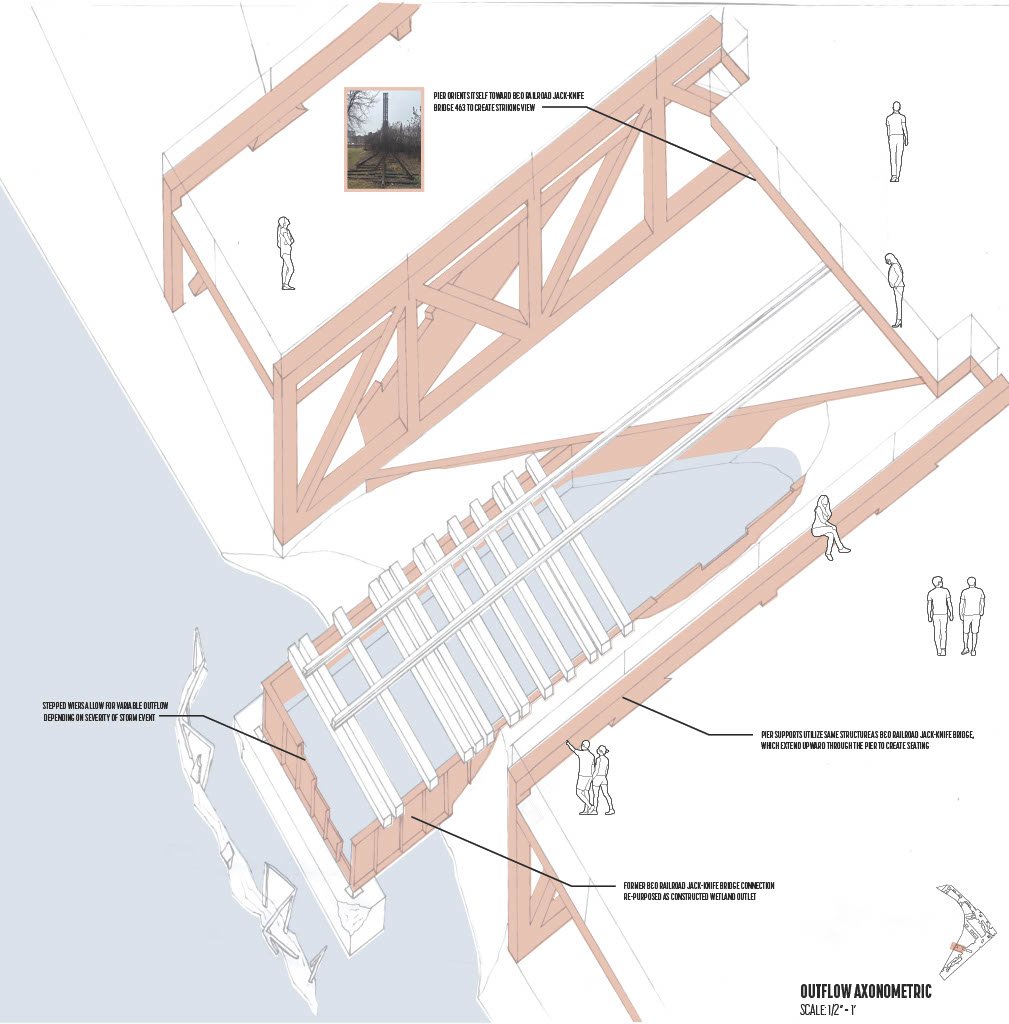

Turning Point can be boiled down to three H’s: Heritage, Habitat, and Hydrology. Park goers who visit this site will find themselves traversing massive piers, all oriented in the direction of a piece of Cleveland’s history along its river’s bends. While on these powers, views to the ecological design drivers are created directly under one’s feet through the utilization of steel grating to allow for a transparent view of nature working below. The two main pieces of ecological boon on the site are the large constructed wetland. Capable of cleaning massive quantities of stormwater runoff from downtown before it reaches the river, and freshwater mussel beach located at the northern leg of the site around the Cuyahoga’s final bend before meeting Lake Erie. This newly installed habitat not only creates a space for a species that was long ago evicted from the river due to industrialization. It also cleans the river through the mussels feeding, continuing the effort begun in 1970 to return the Cuyahoga to a healthy river that is able to be enjoyed by plants, animals, and humans alike. Gallery spaces, cafe’s, and classrooms are located around the site in a campus style, allowing for engagement and interaction to occur at all main features of the landscape.

Cat Marshall

Independent Landscape Architecture design project, completed under the direction of an individual advisor selected from the graduate faculty, extending through two semesters. A Masters project is different from a graduate studio in that it is a study that you formulate for yourself and undertake, largely, on your own. It is also the culminating project of your graduate tenure and is therefore representative of your development during your course of study. Students of landscape architecture are expected to use their design vocabulary of drawings, diagrams, sketches, and maps exhaustively during the masters process.

Aya Keskeso

Comfort For All While Climate And Homeless Populations Rise: Welcoming Unsheltered Teens Aging Out From Foster Care To The Coummunity

Current population trends project an increase in homelessness to three billion people by 2030 according to UN-HABITAT. Moreover, the planning and urban design of cities' public environments typically do not provide safe climatic conditions for current and predicted homeless populations. The author's research looks at two cities in the United States as case studies, documenting current social justice issues related to climatic challenges confronting the world. According to the UN, temperature will increase by 2.7 degrees F in 2030

Current research on social justice in landscape architecture focuses on homeless youth populations not tied to a community or public resources in climatic regions facing climatic stress. The paper examines how landscape architecture can design safer environments, public amenities and offer shelters in our urban cities. This research focuses on: New York City as it has higher predictions of temperature increase, colder winter, drastic population growth and exasperating health issues due to UHI, solar flares, UV, and water scarcity.

This research uses three methods and theoretical projective practices in landscape architecture and architecture to study the homeless youth, which are Climatology, Sociology and Psychology. Also looking through the lens of Victor Olgay, Hood design (Lafayette Square), and Wiiliam Whyte.

1. Climatology:

Designing outdoor spaces for the homeless population involves considering climate-resilient features and addressing this demographic's specific climatic needs and vulnerabilities (Olgay 1963).

2. Sociology:

How can landscape architects address the physical needs of homeless youth and consider their social conditions or the quality of urban life, dignity, and integration into the community through social interactions (Whyte 1980)

3. Psychology:

Landscape architects use principles from environmental psychology, Biophilia, sensory design, and more to create spaces that are not only aesthetically pleasing but also emotionally enriching and important for adolescent development with sense of belonging and providing safe spaces for services. (Hood 1999)

The results in the selected sites need to be identified and organized for potential programs in New York City to address youth homelessness. The mission also involves the identification of essential urban typologies and the necessary human-centered design. Further, the design approach is committed to articulate the imperative social and political changes required in the future.