Caleb O'Bryon

which we can study the essential qualities, properties, behaviors and symbolic value of structural elements, as well as the impact of these on the design of the built environment. It also allows us to classify structural elements according to type, and to compose these elements in syntactical relationships that communicate ideas effectively and create places that support human habitation. Typology also affords a deeper probing of the logic of form and fosters new relationships between structure and aesthetic theory. By engaging students in hands-on lab exercises, explorations in morphology and discussions on theoretical texts on typology, structure and aesthetics, this course teaches students to infuse logic into the design process through direct observation, investigation and experiment. It also emphasizes the mutually defining roles of intuition and scientific method in the design process.

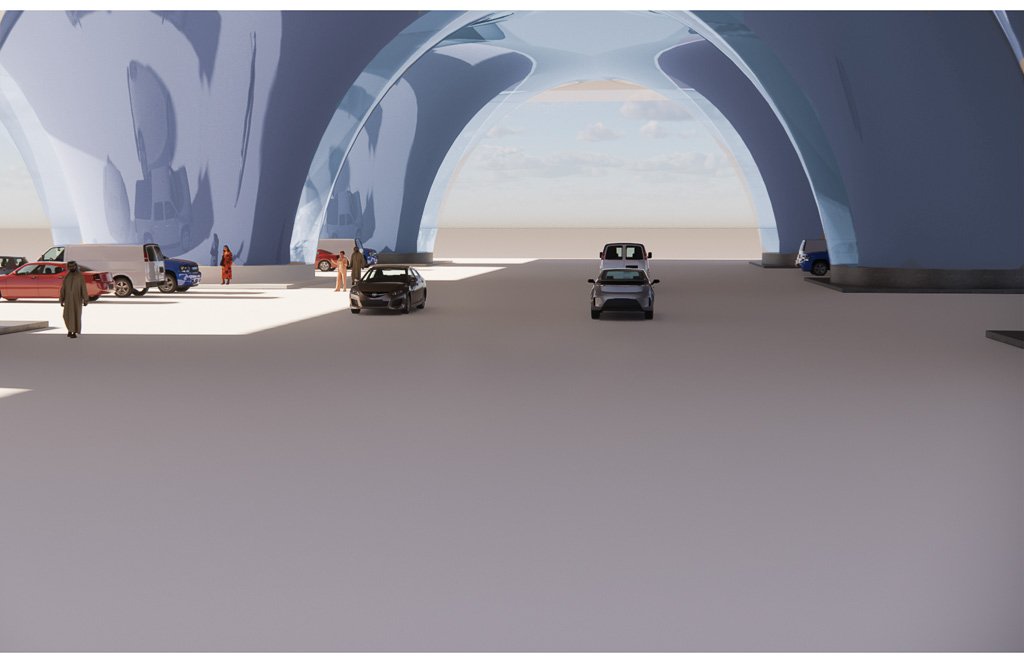

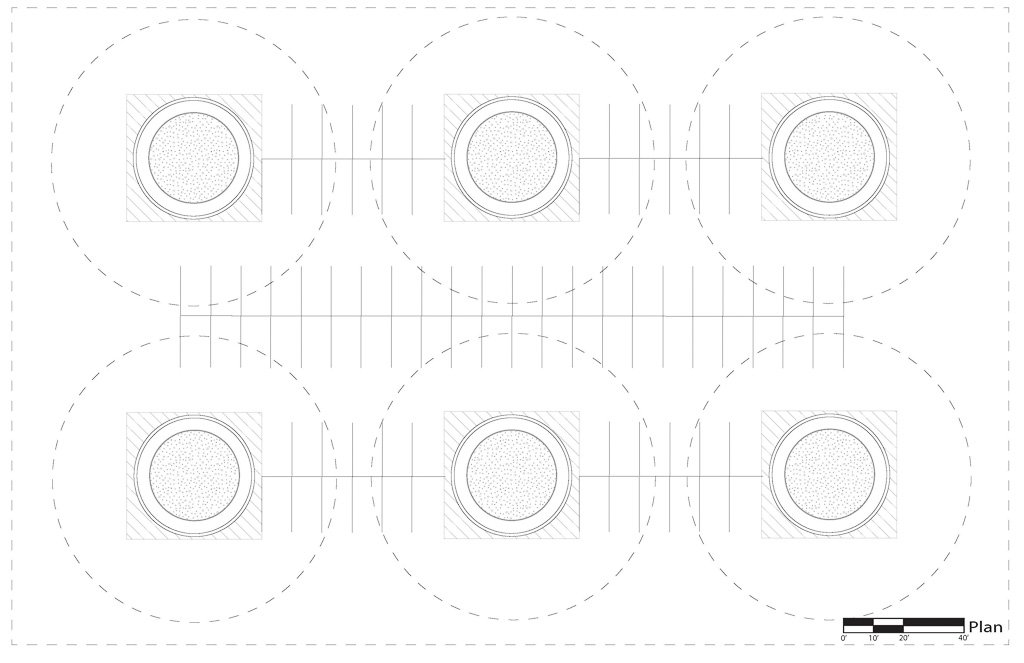

David Wellman & Nicholas Alexander

Parking with the Fishes

Much like the form finding process of weighted strings to create inverted funiculars, the forms generated through the process of melting acrylic with a layer of sand on top of it. These forms are the path of least resistance when supporting the material above it, thus rendering the structure completely efficient. The purpose of these forms would be to create an interior support of a reinforced concrete column and arch, with an exterior shell of plexiglass, creating an aquarium tank full of beautiful schools of fish that swim up and around cars as you park. Due to the wide arch bases and gradual curves as the material slopes upward generated through our form-finding process, the material will be strong enough to hold massive amounts of water. Those parking in the parking deck below the aquarium will get a wondrous experience of life under the sea.

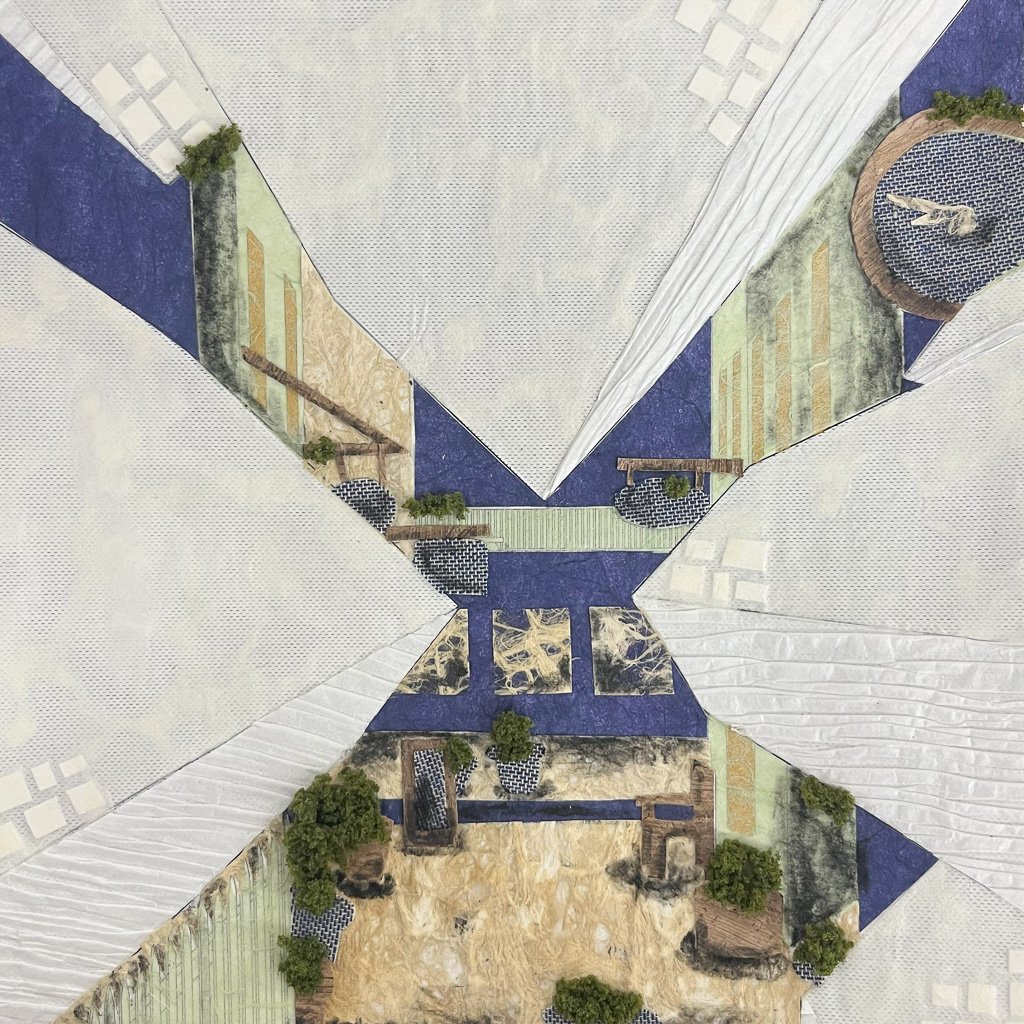

Ellen Ethridge & Claire Palopoli

Up in the Air!

At the beginning of the form-finding process, we knew we wanted to do an inflatable structure. Before diving into any physical processes, we looked into more playful precedents like the INFLATOCOOKBOOK by Ant Farm which was a book consisting of all the different ways that anyone could construct an inflatable structure. From there, we tested different iterations of slime formations. One way was to inflate slime into cages which didn’t end up working due to the slime consistency and limitations of the cage. Ultimately we chose a draped form due to its interesting way of warping around itself. First pillars made of beads are randomized systematically through a grid system placed at intervals.The pillars are easily situated and can be set up in any fashion along the grid lines. Then, slime created by mixing glue, contact solution, and shaving cream is draped over these pillars. Lastly, the slime is inflated with a straw, creating a unique form with every iteration and vast open spaces are created. Our structure is intended to be a temporary and moving art exhibit. It can be easily constructed and taken around the country, most frequently placed in big cities within their natural parks. Although the construction process is the same in each city, a new, slightly different form will be created through the new pillar arrangements and the slime's unique properties. This adds to the wonder of the art exhibit and attracts visitors to each installation. It also challenges each artist who uses the space to adapt their art exhibits to the differing forms of the structure. The structure's impermanence allows cities to attract tourism without worrying about a permanent new structure in their park. The inflated structure is a sight to behold, but only for a short while before it is moved to a new location and reimagined.

Carly Preattle

Through a series of related design exercises, this course explores human scale and the ways human beings perceive three-dimensional objects and spaces. Engages students in reading, writing, research and reflection about scale and perception in architecture.

Claire Palopoli

Dream[E]scape

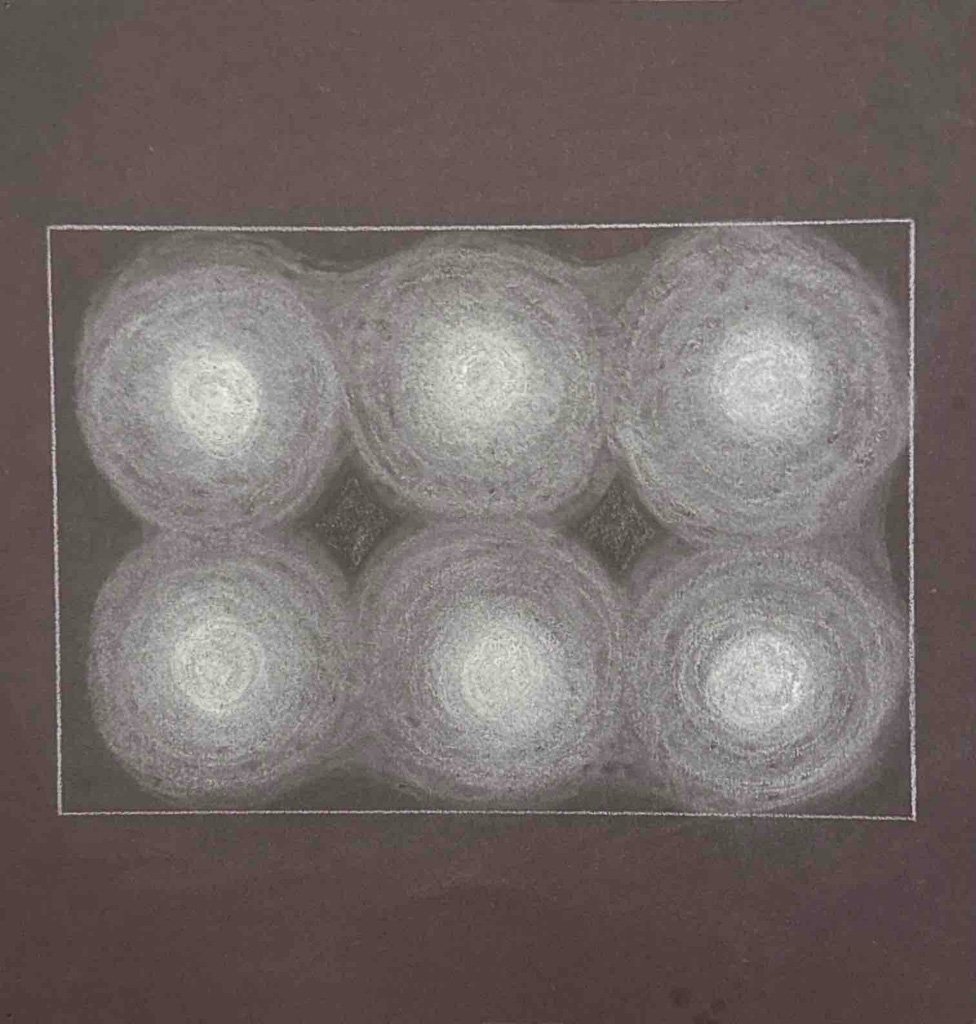

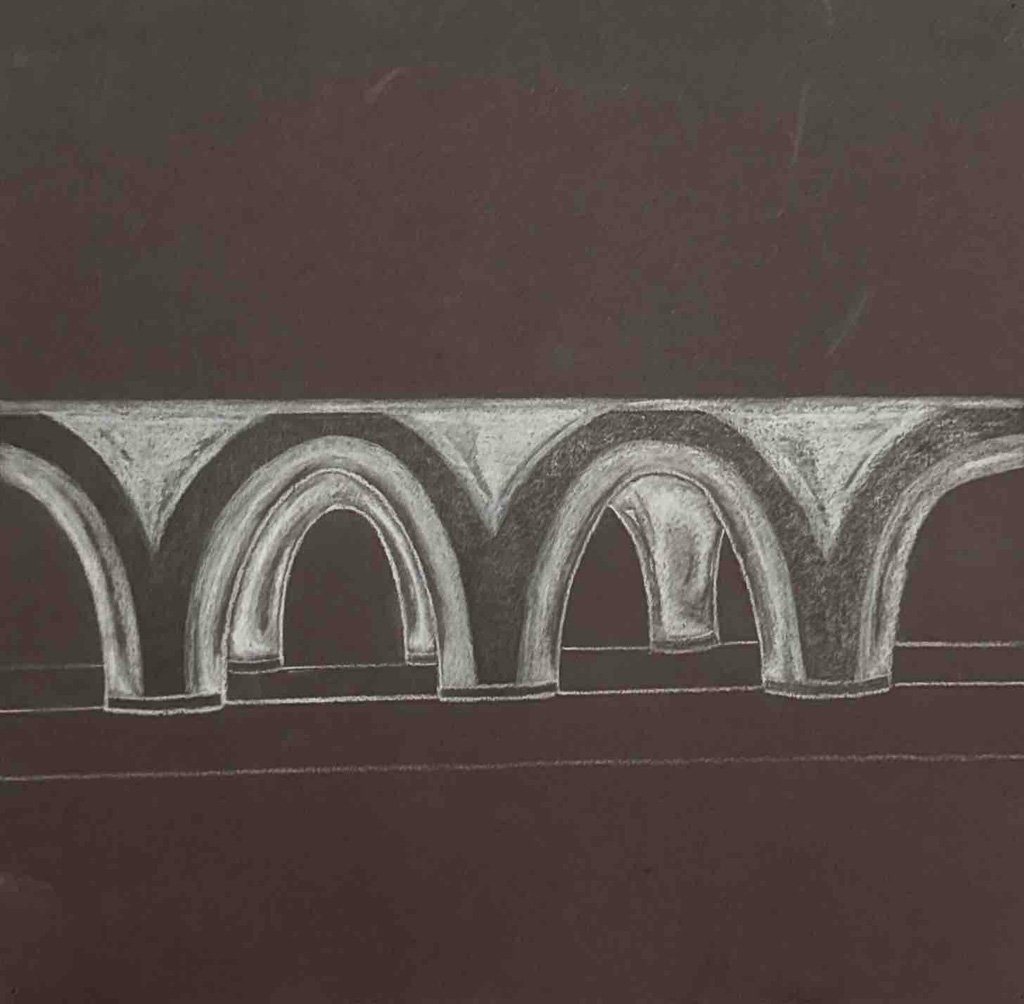

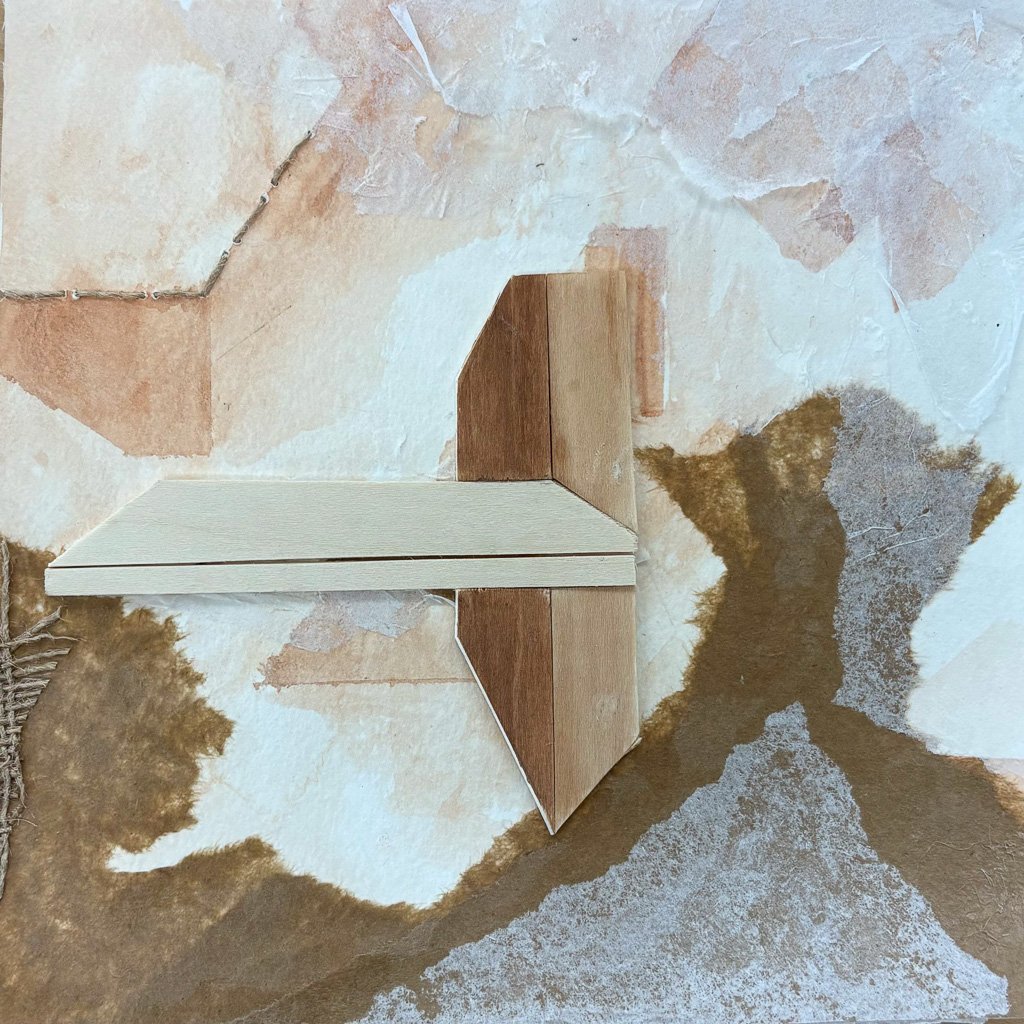

Throughout the semester I wanted to investigate how our memories and dreams can alter throughout time. By analyzing spatial qualities of known and familiar spaces, I curated a dreamscape not yet affected by time or emotion. Here the spaces blend into one another creating a cohesive memory, yet still somewhat clouded by blank spaces due to not fully recalling that exact details of the location. This leads to my first model which portrays a modulating perception of the first perspective drawing. The viewer is able to manipulate the pieces into whichever orientation they may conceptualize. Having an almost playful and nostalgic quality, the model represents how basic pieces of our memories tend to stand out. Later on, the dreamscape becomes more confusing and disjointed. These initial spaces are altered to create a sense of surrealism that is often associated with dreaming. While the drawings are darker, they still contain a minimal sense of comfort that the original perspective showed. My second model of the semester reflects this changing dynamic in the dreamworld with its harsher material and form. Rigid edges of the concrete in contrast with warmer wood textures create a dichotomy between the comfort of memory and the frustration of misinterpretation. In the final iteration of the dreamscape, I wanted to portray the peak of the mind’s imagination. The final visualization takes on the darkest and most complex form of the mind. A matrix of lines and planes interconnect with each other emulating possible neural networks. Tucked away in this environment lies the dreamscape that we thought we knew, yet crowded by the long term effects of human emotion.

Ellen Ethridge

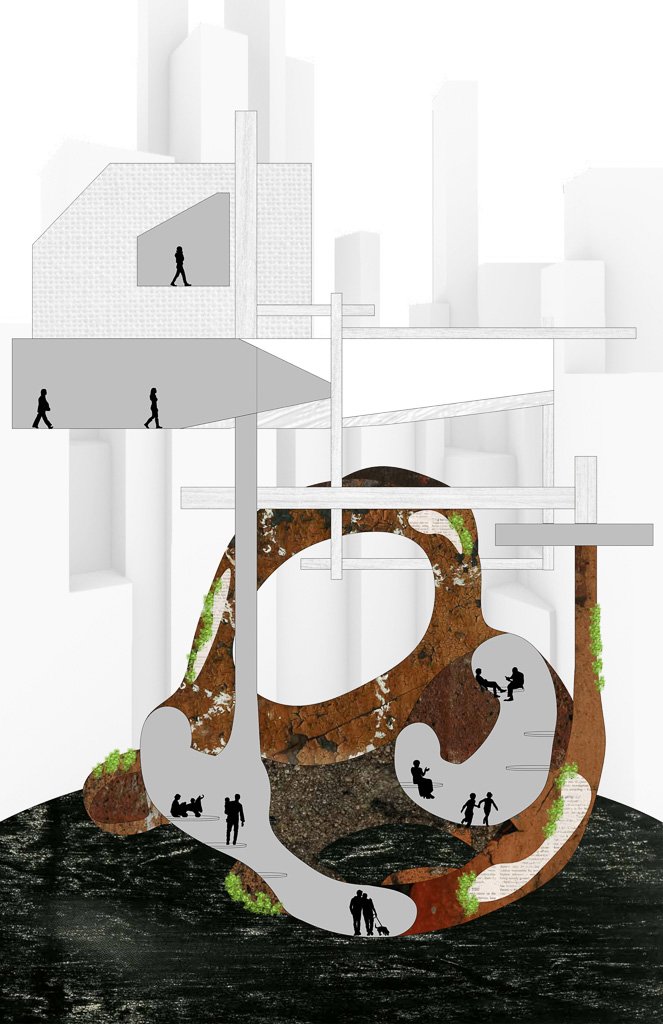

The Battle of Progress and the Past

This project presents a critique of modern architecture through the exploration of dualities of aged lived-in spaces with the clean new construction in modern cities. Connecting modernist architecture to the displacement of people, culture, and history.

The project begins with examining how deteriorating architecture is perceived and interacted with. The typical course of action is the removal and "cleaning" of these spaces which ultimately breaks its unity and takes away its life and vibrancy. I carefully chose materials that represent human presence in these spaces, asphalt, denim, greenery, leather, wood, concrete, and other textiles. Utilizing materiality to depict the two battling perspectives allows the viewer to see the contrast visually and also feel immersed in it. Able to touch and understand the spaces, it feels familiar to them.

The balance of this duality of spaces is also looked at to further the understanding of their perception. The new construction is shown as a looming threat to the old architecture, slowly encroaching upon these spaces. Sometimes the spaces become entangled and other times the new architecture is built straight on top of what was previously there. The modernist buildings in my project are forcing your perspective to the sky, upwards, to progress. However, when you shift your perspective forward on the surface that is where real progress and life occur. The project plays on these two perspectives diving into what progress should look like.

Architecture needs to exist in harmony with the history that it inhabits, considering environments, people, and culture. Knowing how people fit into these spaces, how it affects them, and how they live within it. Considering avenues such as restoration and reuse before breaking ground for construction. Understanding the perception of these spaces is key to providing balance in design while furthering progress in innovation and community.