Gregory Stroh

This studio investigates the relationship between architecture’s various modes of performance. These include material assemblies, structural design, environmental systems, and less technical issues such as compositional systems and aesthetics. Particular focus will be given to the physical integration of components and systems, visual integration of materials into the composition of the built work, and performance integration of shared functions. Students will develop a more holistic approach to building design by integrating technical systems with aesthetics and ecological performance.

Integrated design is a comprehensive, holistic approach to design that combines specialist knowledge to consider all the factors necessary for a decision-making process. Designing buildings in an integrated fashion considers architecture, structural engineering, MEP, passive environmental strategies, and various sociopolitical stakeholders. The aim of creating a collaborative relationship between disparate disciplinary knowledge in the design of buildings is often to produce sustainable architecture. This approach eschews specialists working in isolation in favor of solutions greater than the sum of their parts. (1) Throughout this semester, experts in building design outside of the architecture discipline will be brought to the classroom to collaborate on your studio project’s design, simulating an integrated professional practice relationship.

Marzieh Jafari Doost Khaledi and Nathan Carpenter

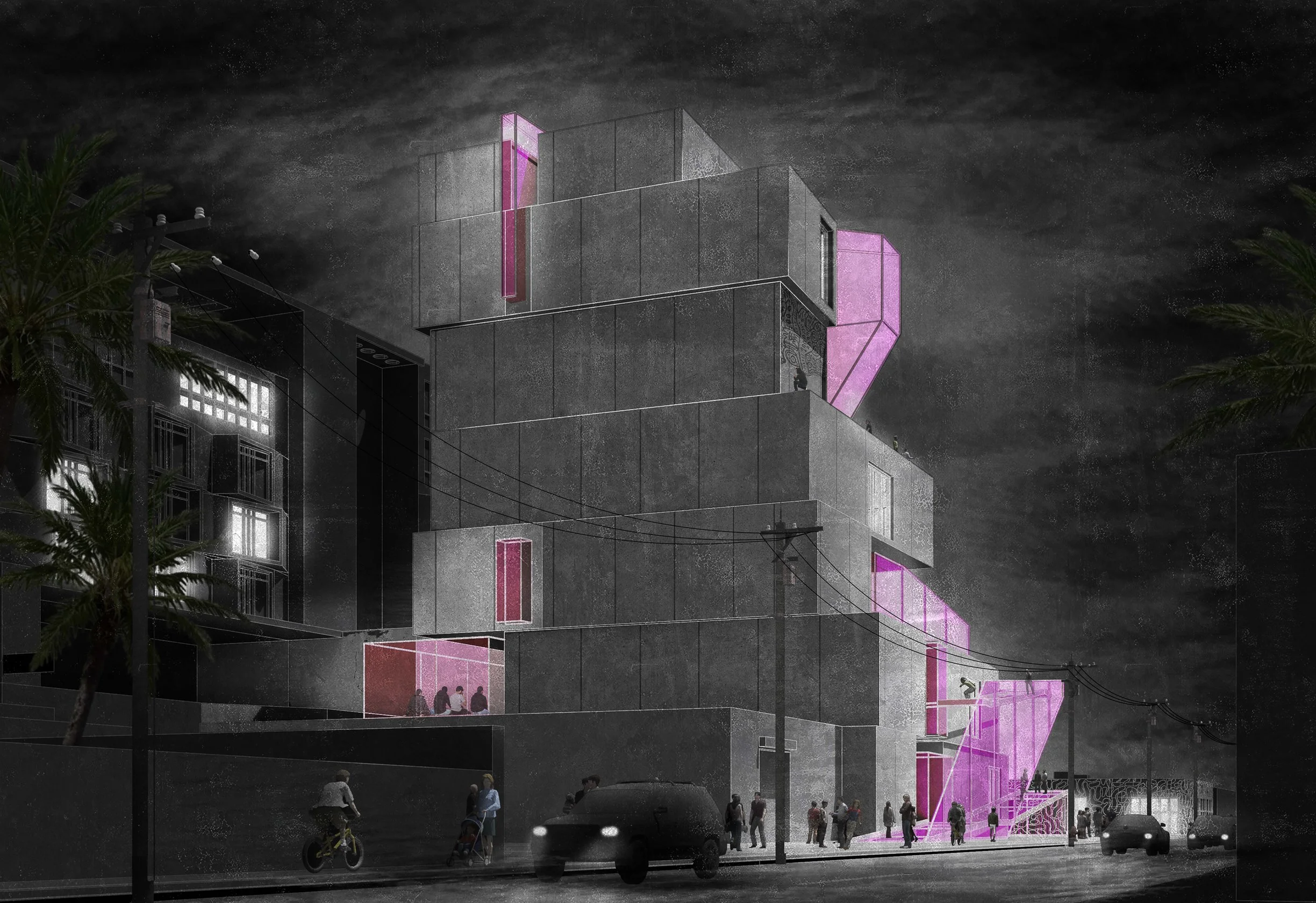

Vertical Street

Given the richness of Miami’s diverse population and the many challenges of urban inequality, our project performs as a democratic asset for Wynwood. It does this through re-thinking the idea of bazaar, infusing it with mobility and making art for people to share. The vertical boulevard augments the experience of moving through and around the building as you encounter art, social engagement, and events throughout the space.

The project is conceived as a continuation of the street, bringing people during all hours of the day into the space. The vertical bazaar idea carries the promenade from the street into the building while it traverses indoor and outdoor spaces. From street level, the ramps take you through the program of the building, starting in the galleries and going through amphitheatres that bring another form of art into the space, and finally culminating in a balcony space that gives you views of Wynwood, serving as a muse for your art through our art workshop spaces.

The street in Wynwood acts as a social and artistic experience, and that is something that we value and want to enhance in our project. We plan to make this building a 24-hour experience by allowing pedestrians to gather and democratize our space. Using the vertical street to make their own booths, art, social events, protests, or any other activities.

The building itself acts as a blank canvas for art to happen. Using concrete walls, similar to what is seen now in Wynwood, we can create space for art to be created and implemented into the building, inspiring people on the outside as much as the galleries do on the inside. The greenery and the perforated metal panels are also an artistic decision that help foster a sense of creativity in people and bring life into the building to make it look more inviting.

We imagine this space as a place where people will take their morning run, meet up before an event, gather to see what artists we’re displaying and more. A place that admires and appreciates the nightlife of Miami and gives people a place to sell and display their art to get notoriety for the work they’re doing, both on the inside and the outside of the building.

Rachel Bendel and Serene Montgomery

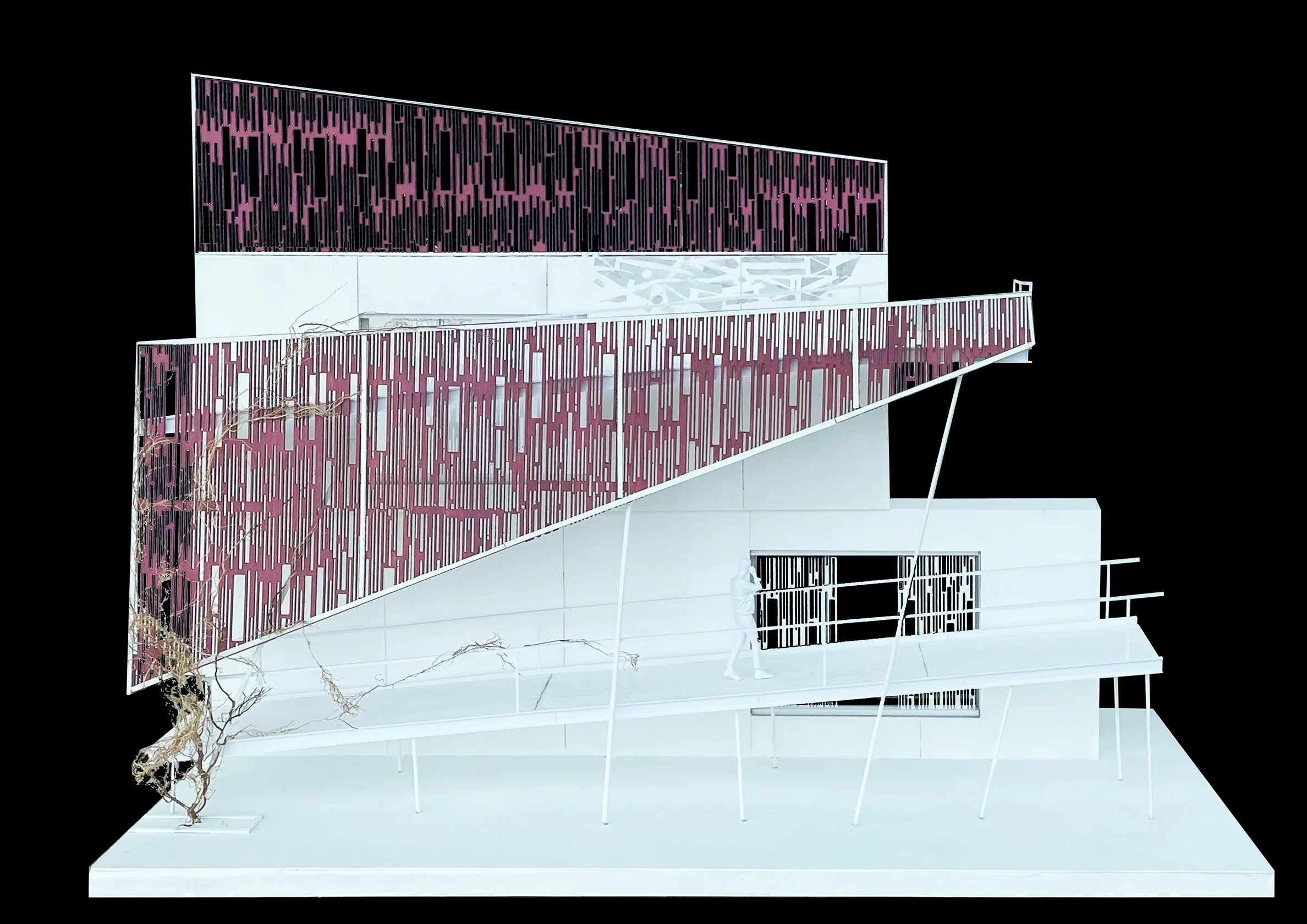

The Veil [MIA 2025]

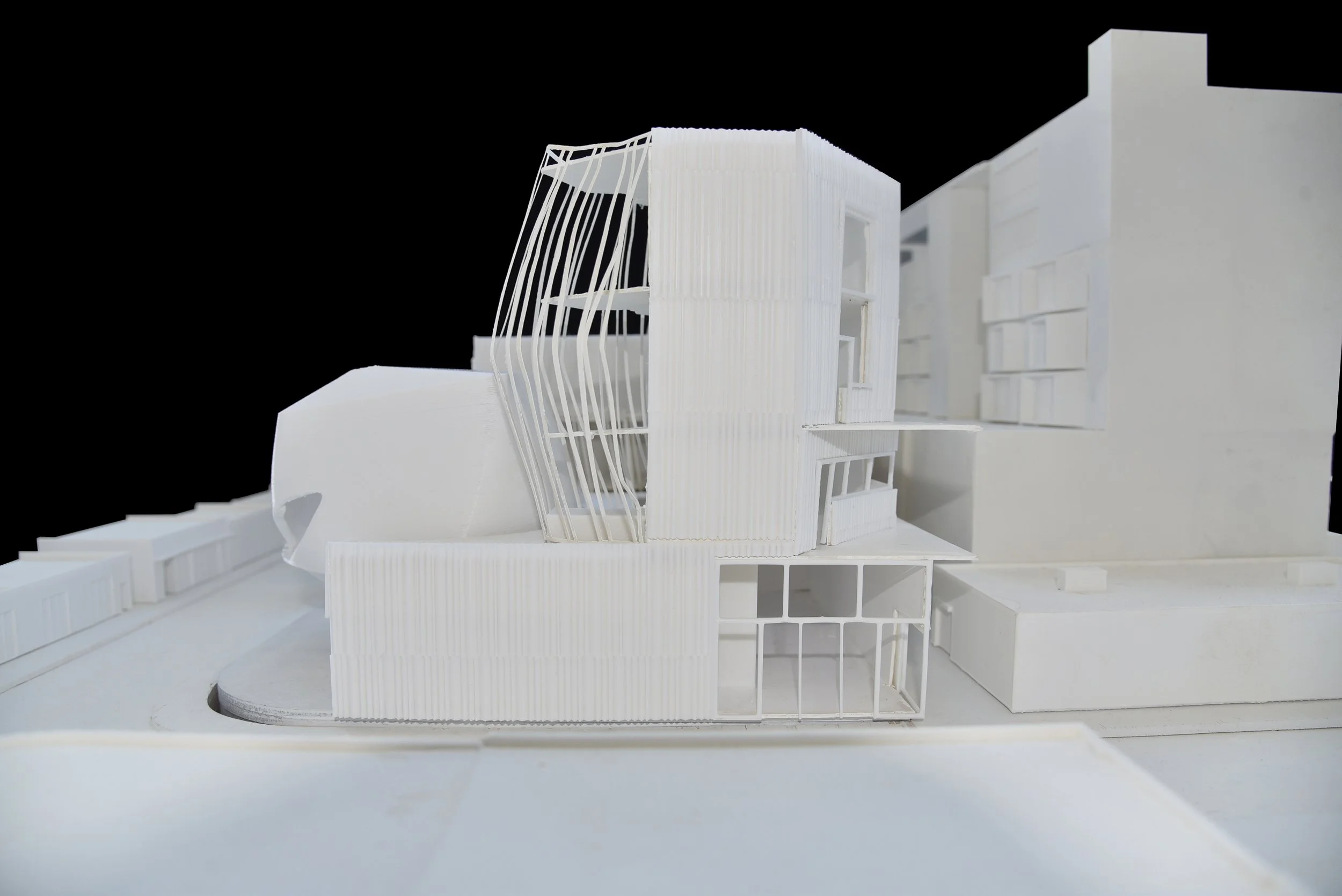

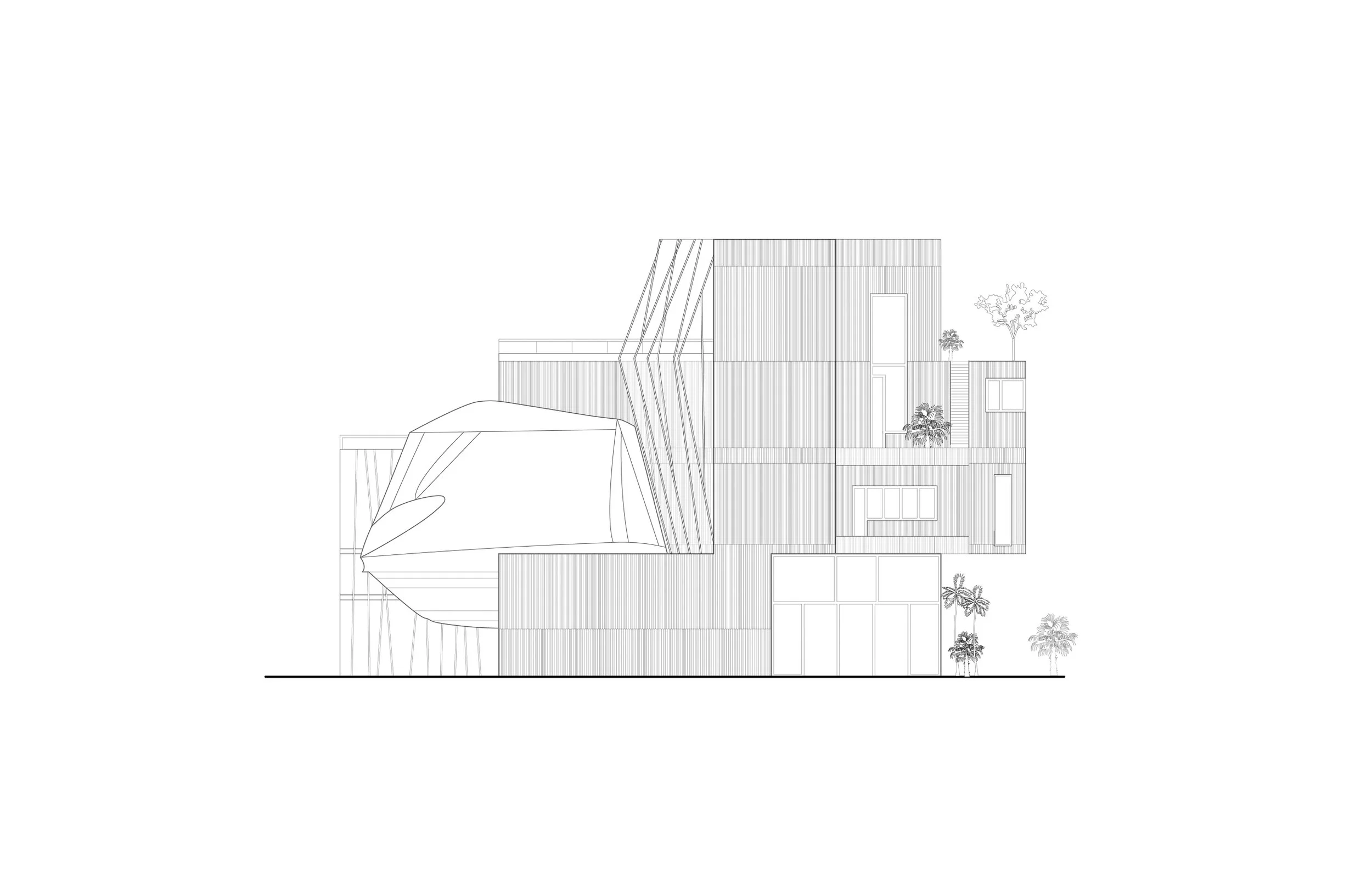

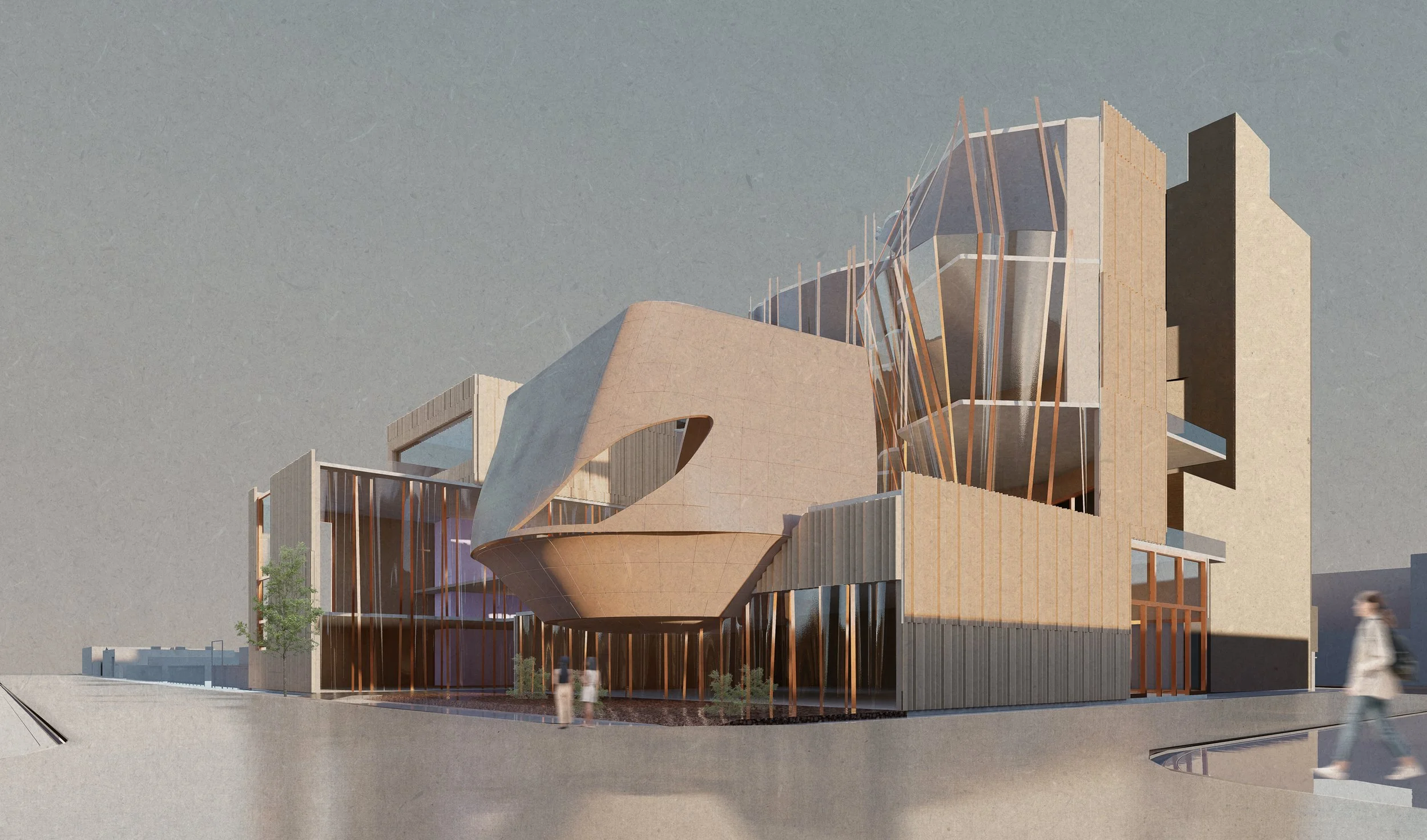

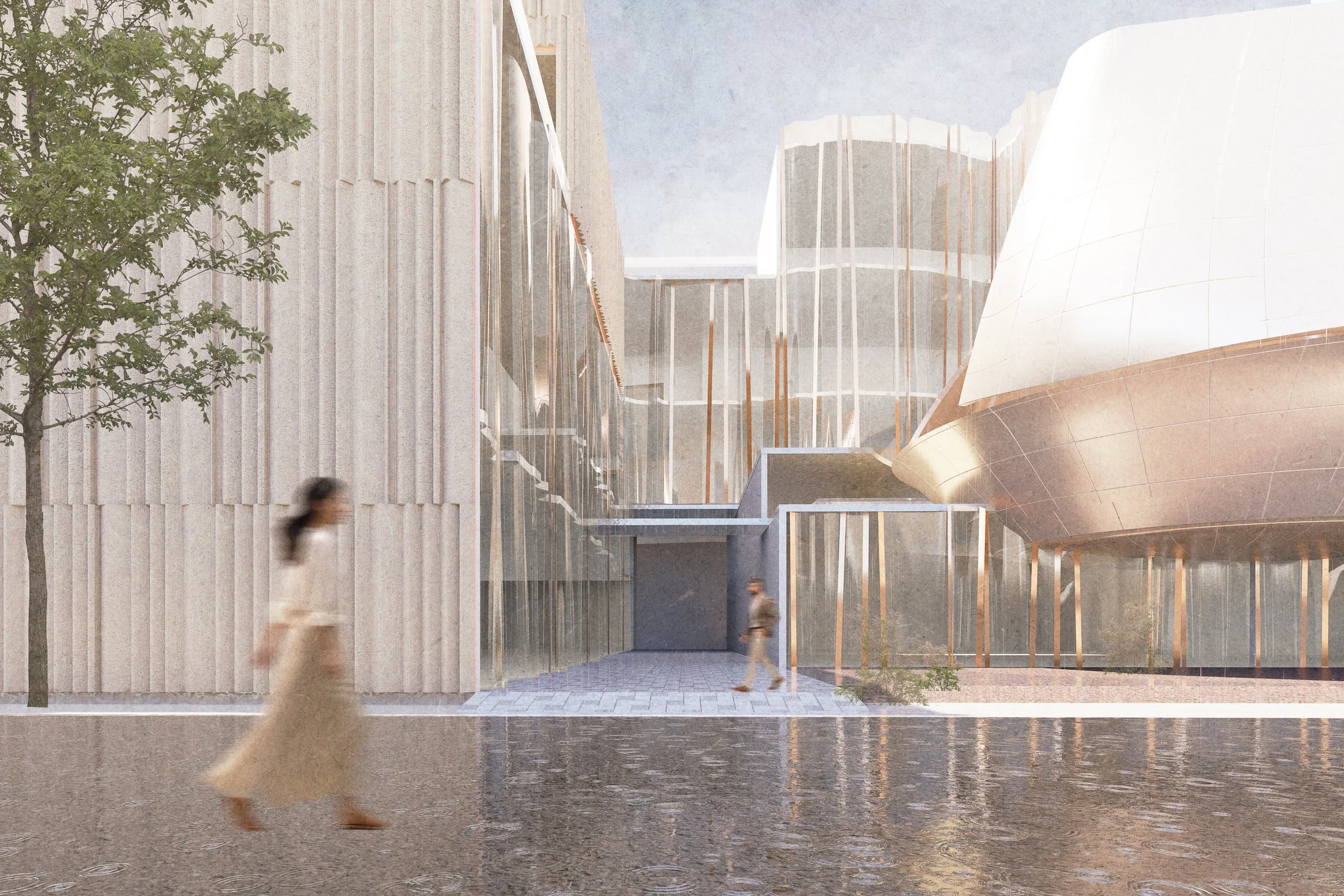

This project imagines a cultural heart for Miami’s Wynwood district—one that celebrates both the everyday and the extraordinary. Two buildings, connected by a slender bridge, bring together art, music, wellness, and community. The design blurs boundaries between performance and audience, interior and exterior, spectacle and daily life. A central path invites the city in, while layered spaces unfold above, offering places to gather, heal, and create. With materials that shift between solid and delicate, the architecture echoes the rhythms of Miami itself.

Eva Brinkman-Sull and Madalyn Capps

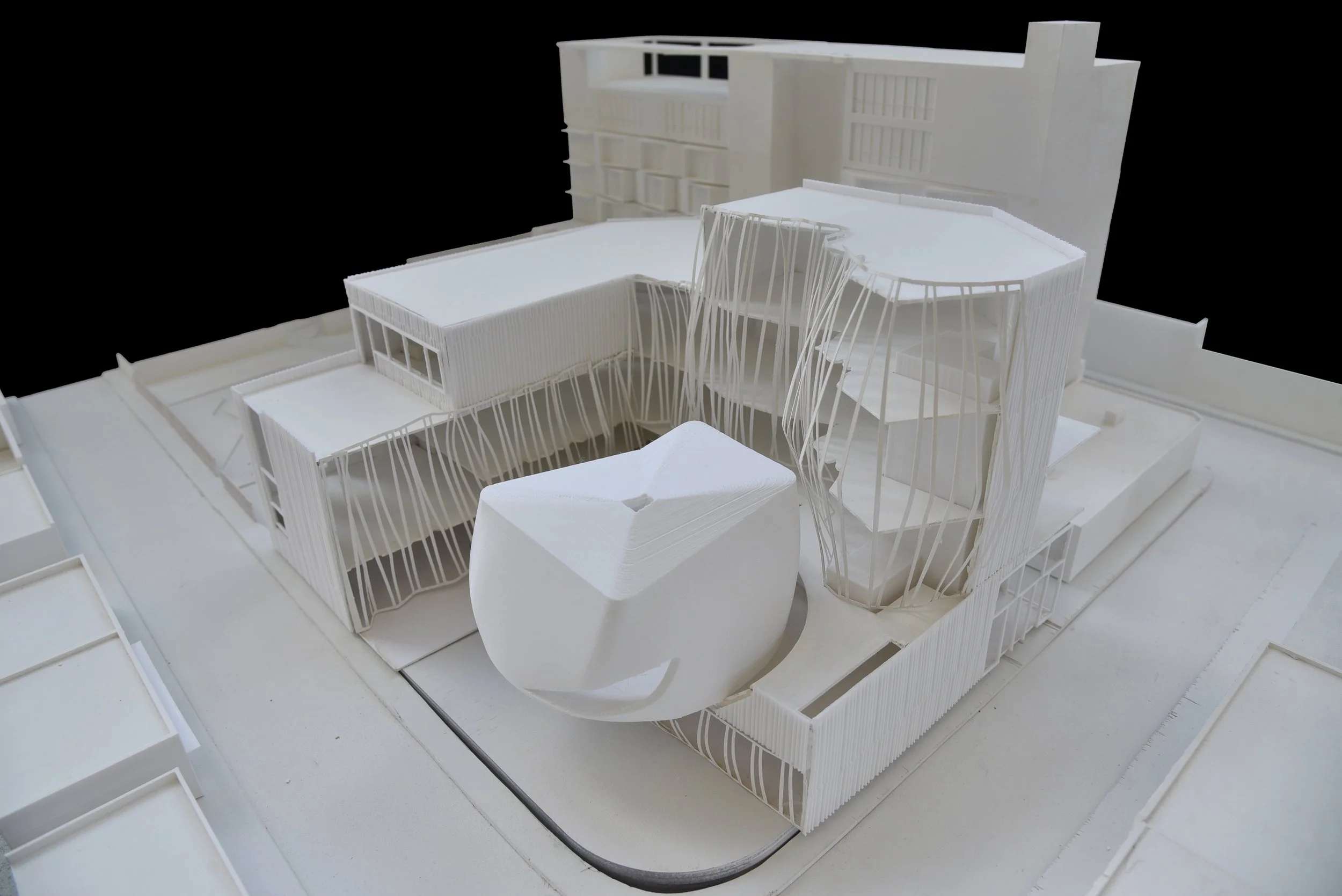

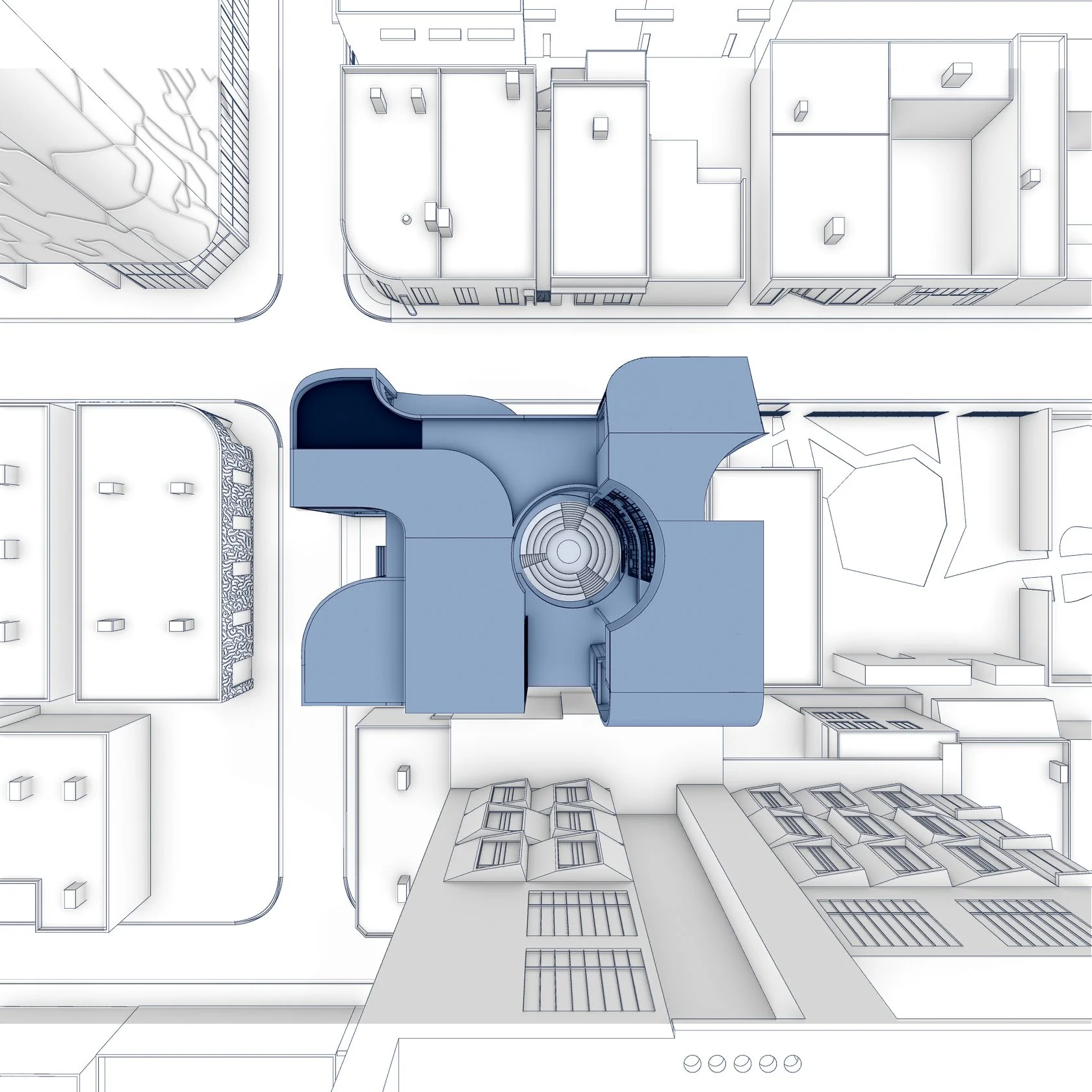

wyn MONOLITH

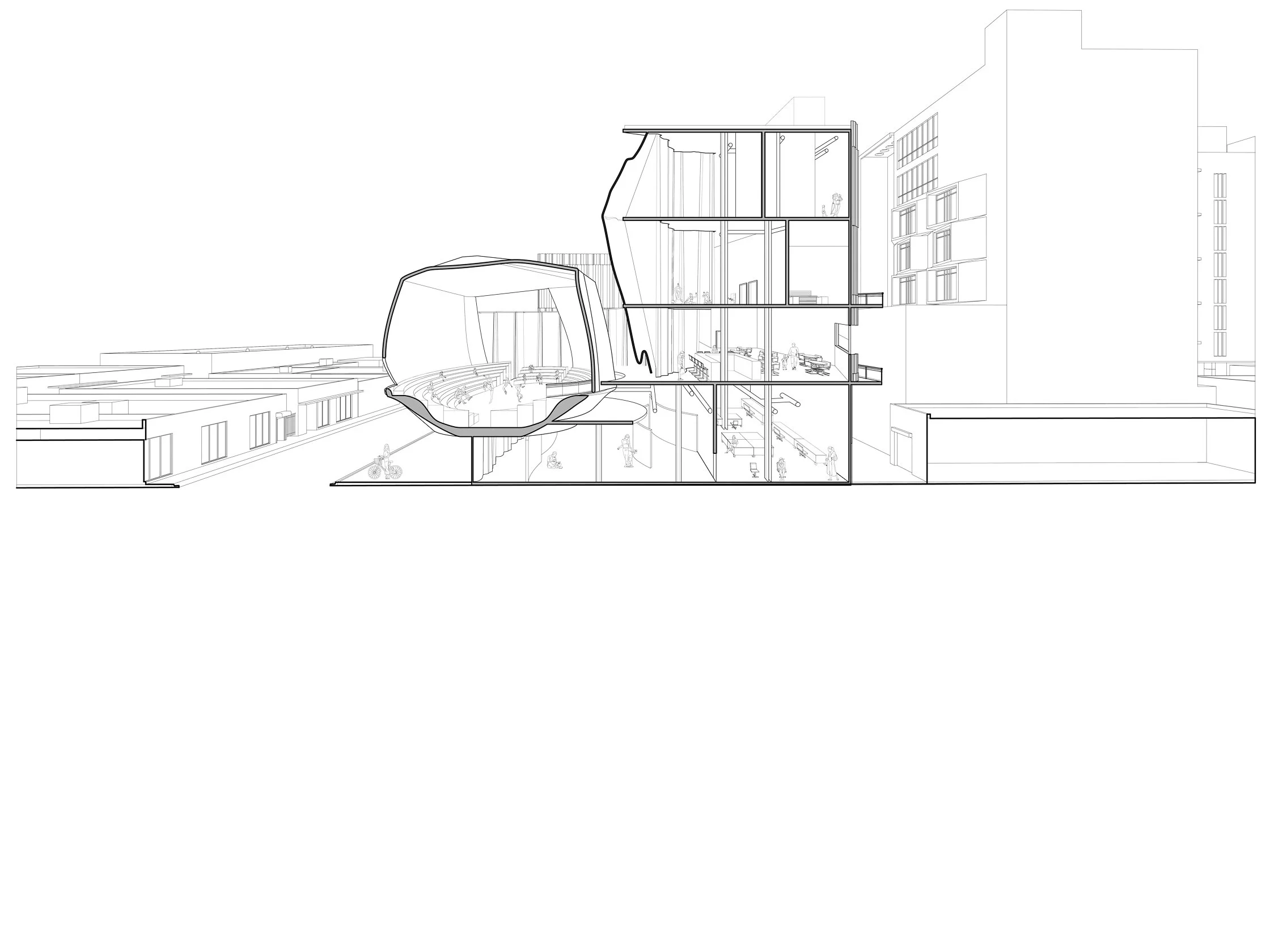

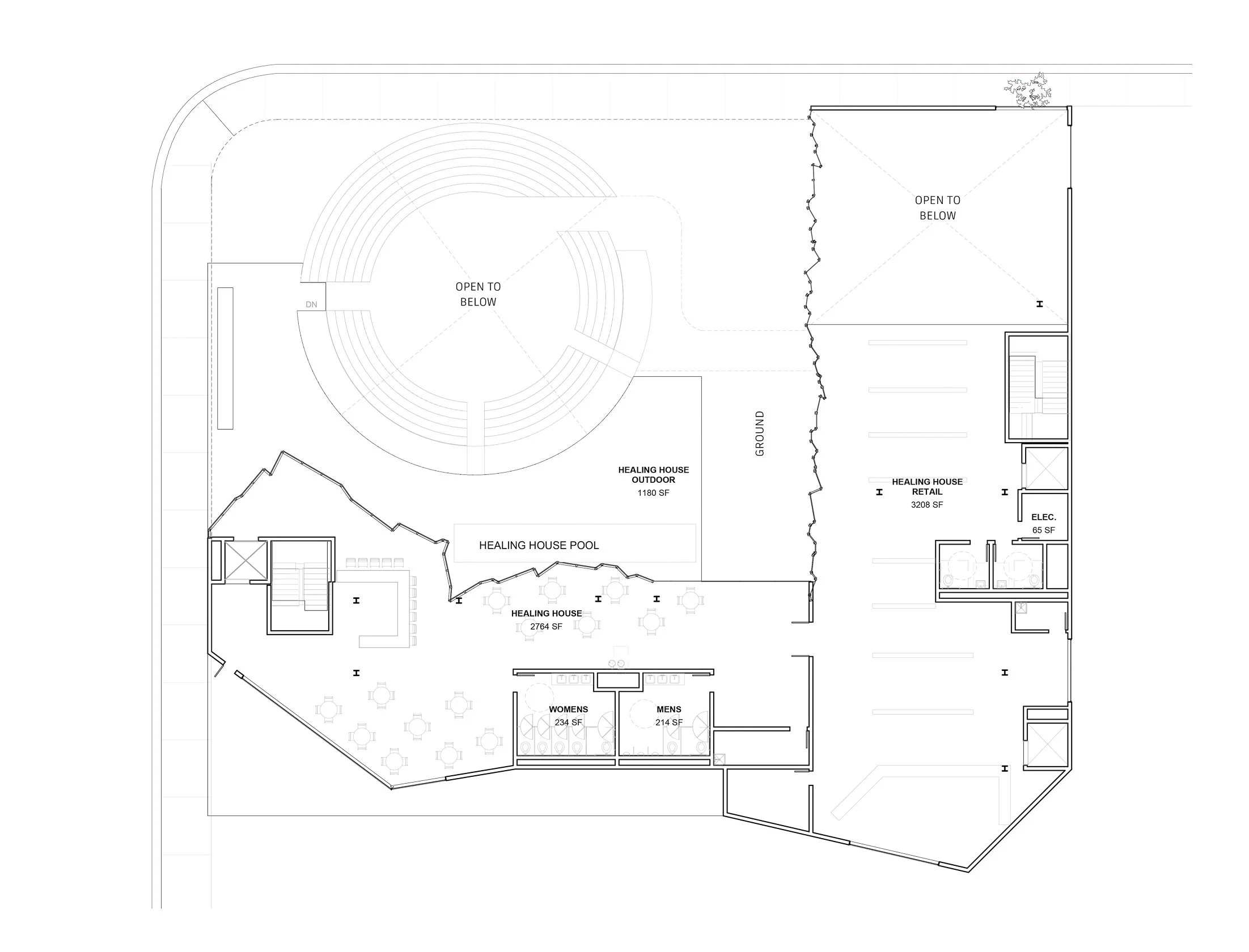

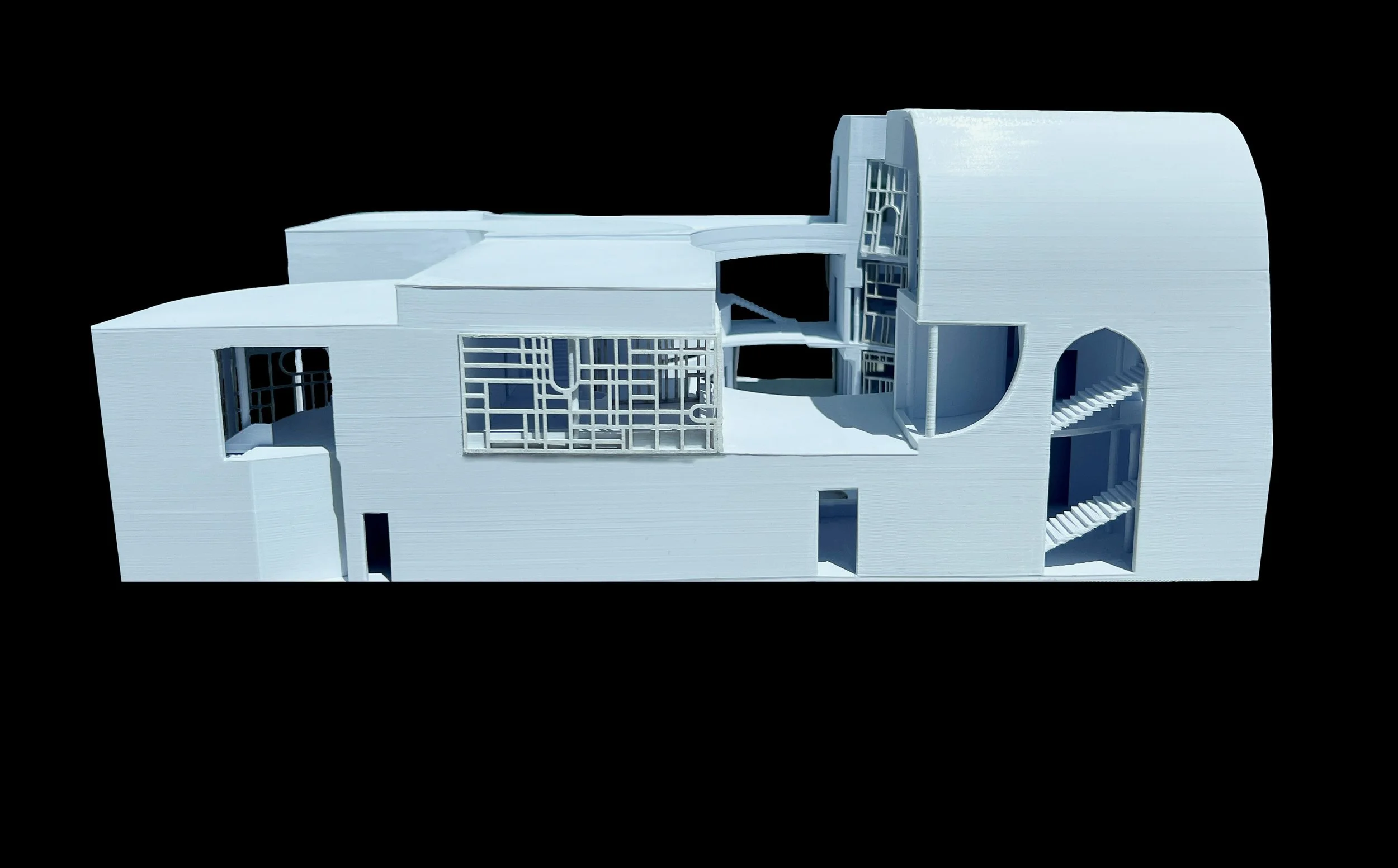

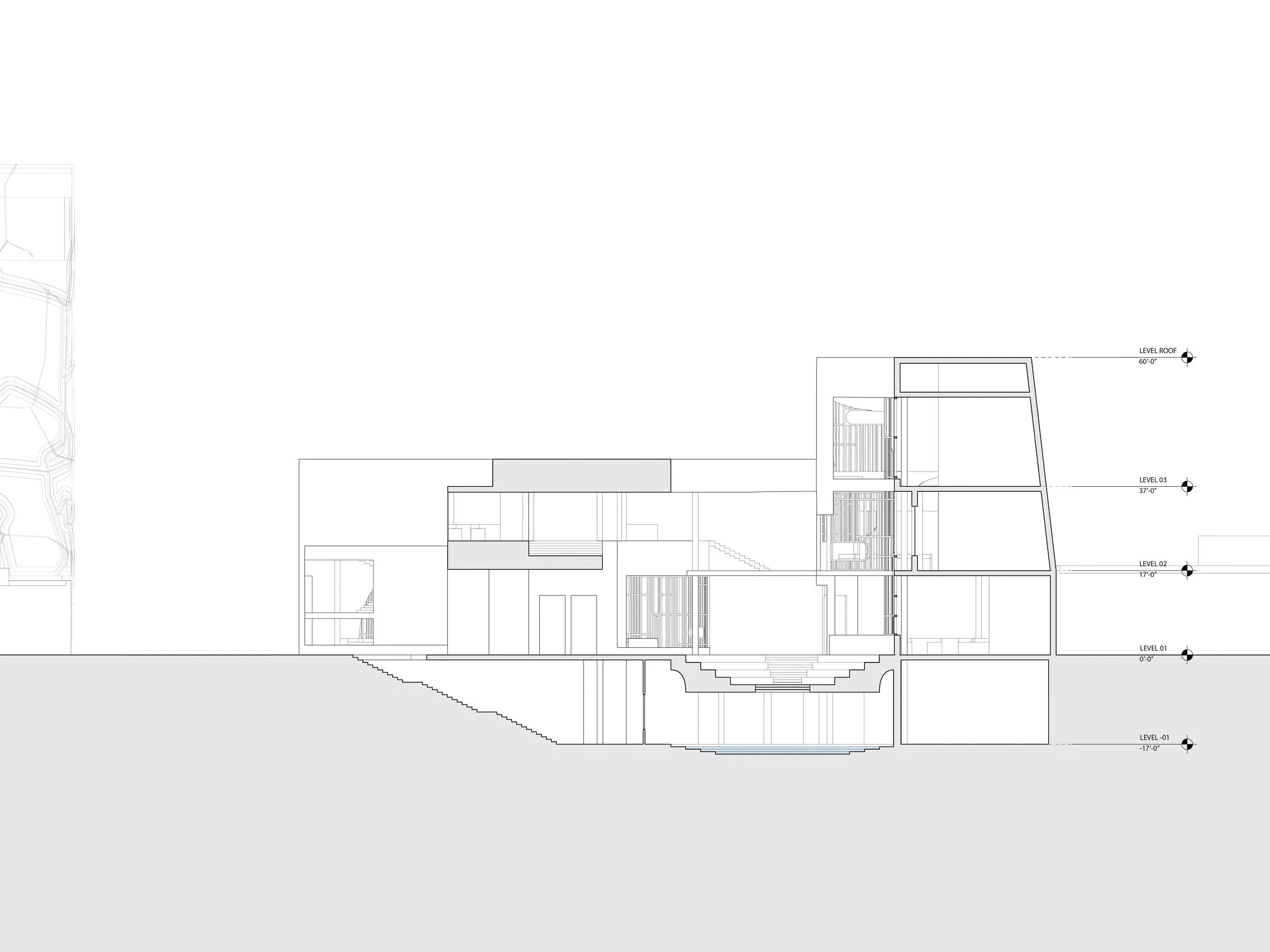

Our project embraces “layered urbanism,” a mixed-use strategy promoting sharing, making, and playing within the community. Unlike the single-use buildings nearby, such as hotels and apartments, our design stacks diverse programs vertically, treating the urban surface as a key mediator. Visual and spatial connections between levels create a sense of continuity, while outdoor spaces like the amphitheater and rooftop plaza encourage community interaction.

Located on a corner lot, the three-story, pigmented blue concrete structure blends open public areas with enclosed environments. Drawing inspiration from Miami’s curves and the geometry of amphitheaters, the design orients itself around a central form that anchors the experience.

The project reconfigures Wynwood’s extroverted energy by juxtaposing density with moments of calm. Below ground, the Healing House features open pools, therapeutic rooms, and meditation areas that offer refuge from the neighborhood’s fast pace. At grade, a produce market and partial gallery extend into the street, activating the block and supporting local vendors. Above, the amphitheater, embedded into the ground, serves as a performance space and social hub.

Upper floors contain galleries, artist studios, and a maker's market, with an outdoor graffiti gallery that maintains a visual link to the iconic Wynwood Walls. A restaurant anchors the corner of the site, connected to the market and gallery below. A sculptural staircase functions both as circulation and centerpiece, leading to indoor and outdoor seating areas with elevated views.

Through its programmatic layering, spatial flow, and material expression, the building redefines how architecture can support culture and community within Wynwood’s evolving urban context.

Ivan Bernal

Escaping sameness while embracing plurality and strangeness, the studio draws inspiration from the literary style of magical realism. It aims to generate a melting pot of cultures and architectures inspired by Latin America and the Caribbean to address Miami's intertwined crises of housing affordability and climate change. These challenges disproportionately affect those migrating in search of safety and stability, often fleeing wars, oppressive regimes, violence, or climate disasters.

Miami has evolved into a vibrant cultural tapestry shaped by its diverse communities. Yet, real estate development often prioritizes financial returns over affordability and cultural representation, leading to standardized and uniform architectural styles that fail to reflect the city’s rich diversity, geographical location, and climate. In contrast, Miami’s population—and its unique ecology of plants and animals—represents a dynamic mix of cultures, styles, and traditions, creating an energetic melting pot filled with spectacles to experience.

Greater Miami and Miami Beach, for example, is over 70% Hispanic, with residents originating from Latin America and Caribbean nations. This diversity underscores the need for architecture that celebrates the richness of the community rather than conforming to uniformity. The studio will explore tropical cultures and vernacular architectures, delving into their methodologies, materials, and sensibilities. Students will investigate South Florida’s environmental and climate challenges, documenting initiatives addressing sea-level rise, hurricanes, flooding, and Miami's severe housing affordability crisis.

The objective is to uncover connections between space, culture, and spectacle; challenge traditional notions of family structures and public spaces; and reconsider conventional building systems. Emphasis will be placed on working with wood and natural fibers to envision linear, mid-rise collective housing structures that embrace Miami’s climate and celebrate its cultural identity.

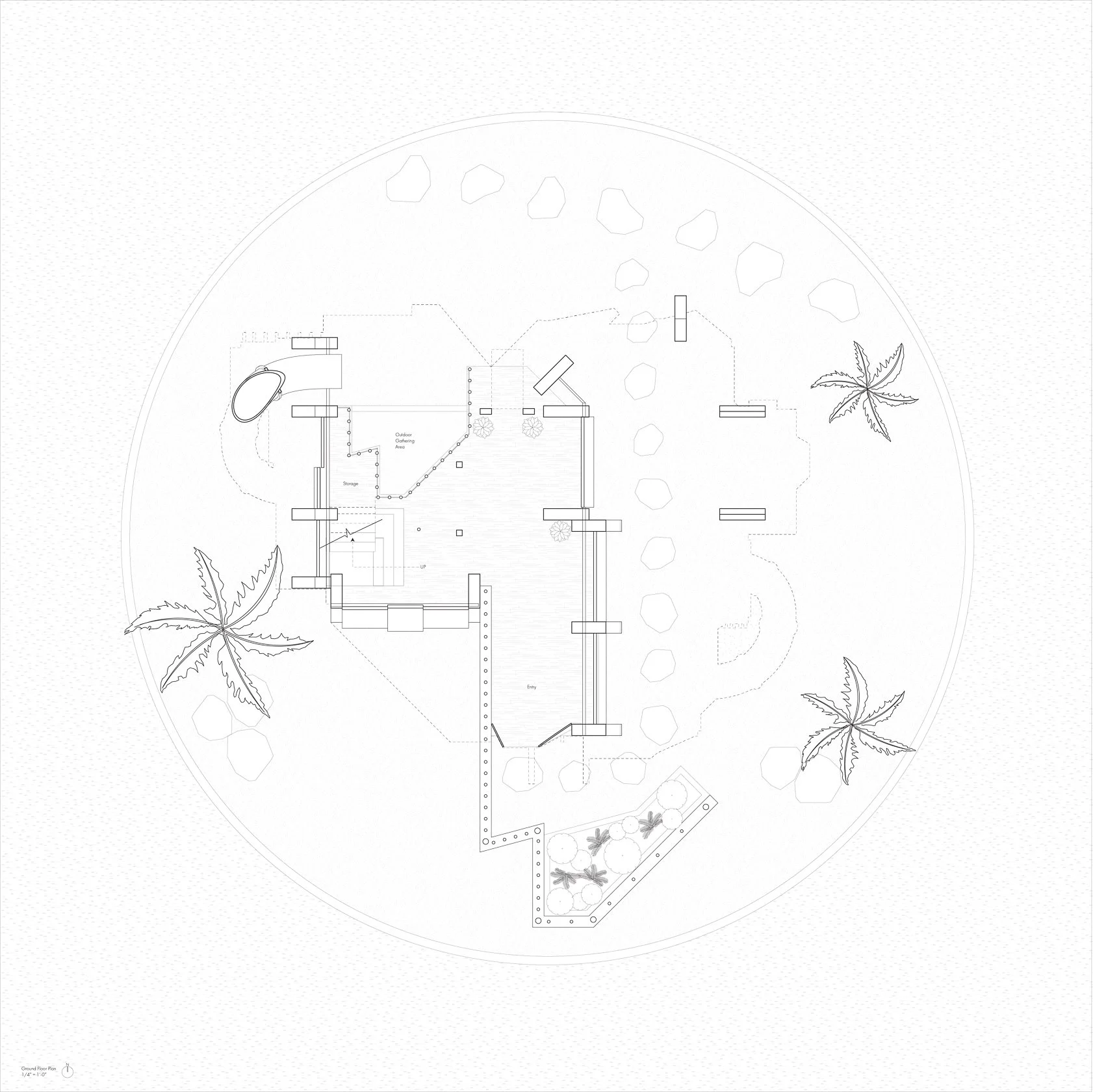

Olivia Carpenter

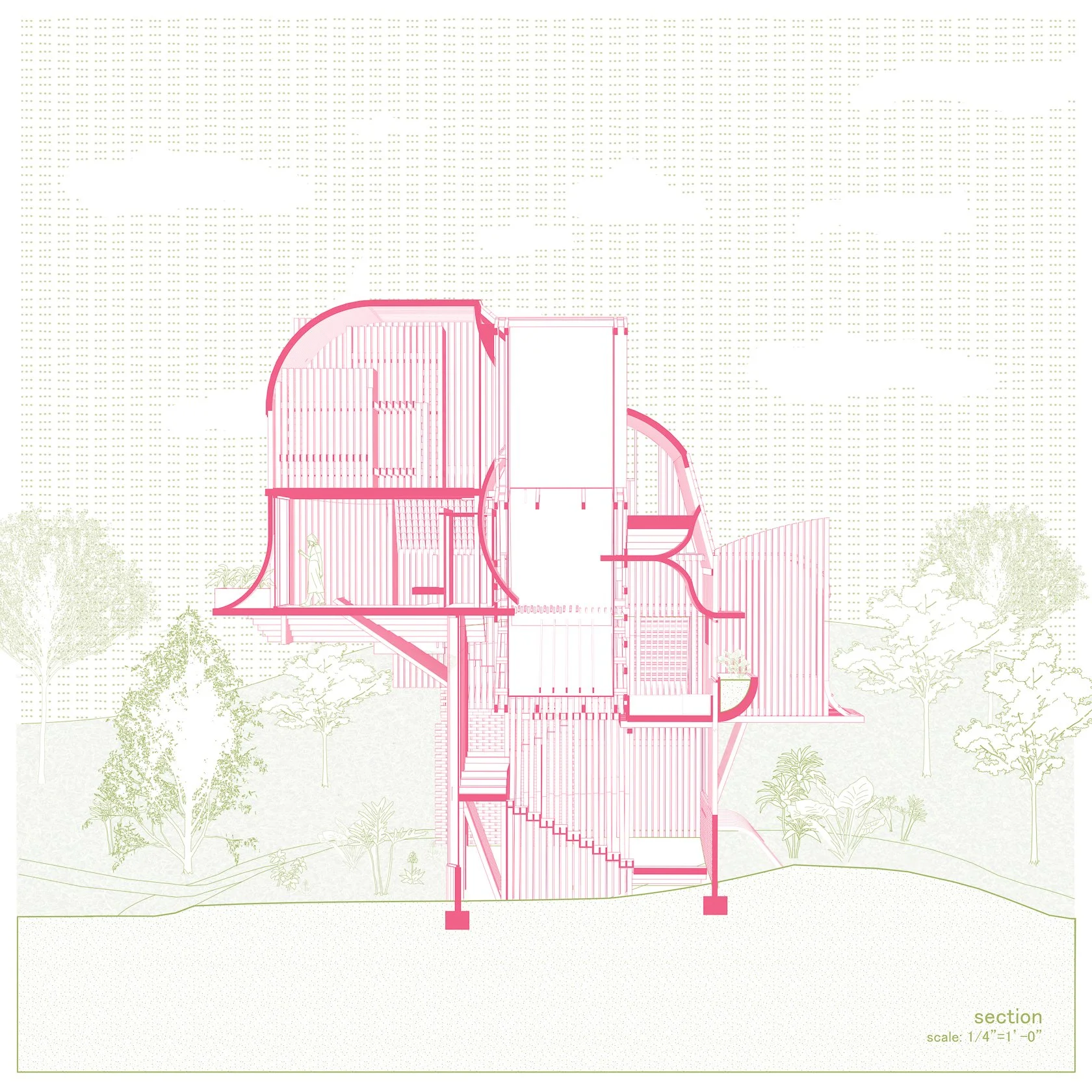

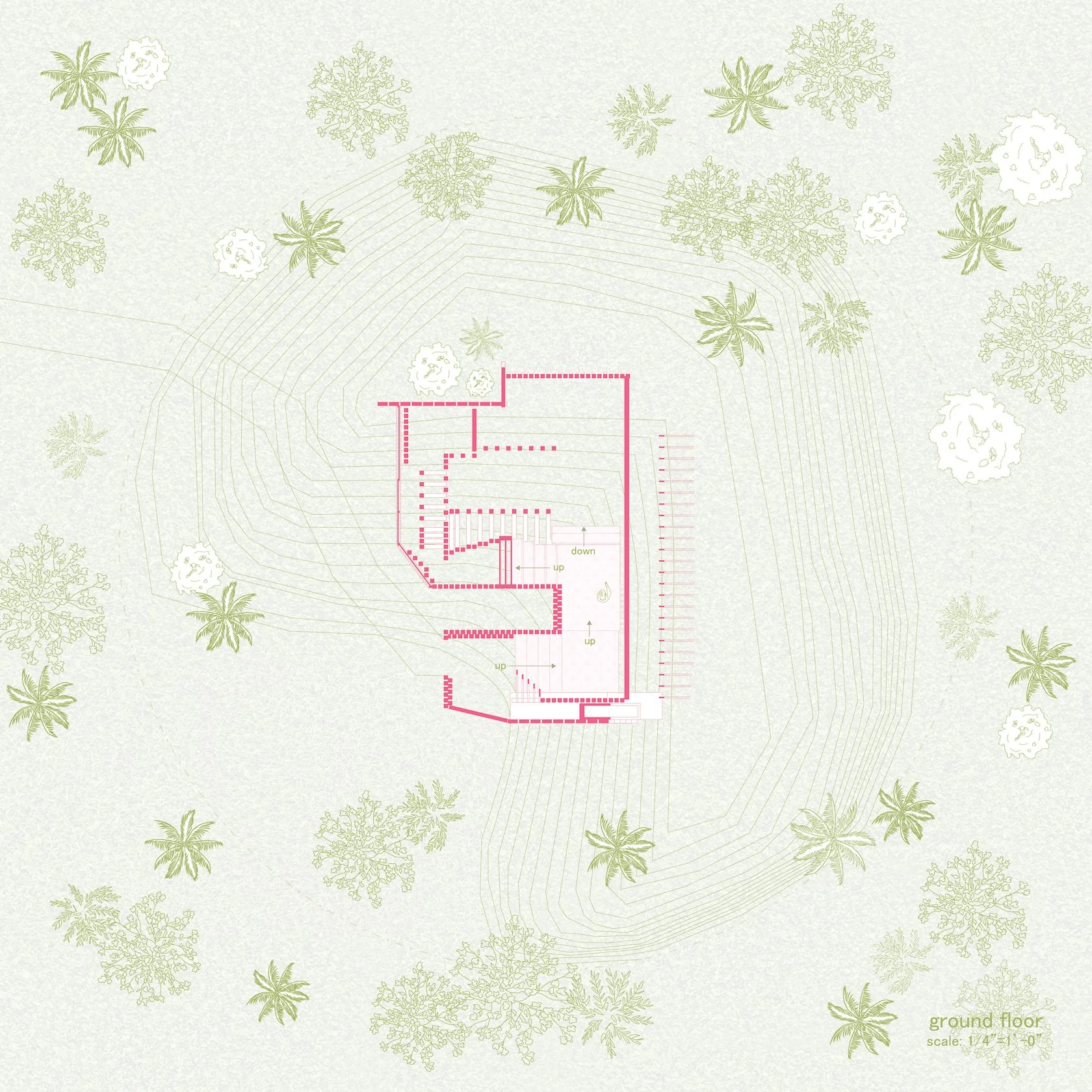

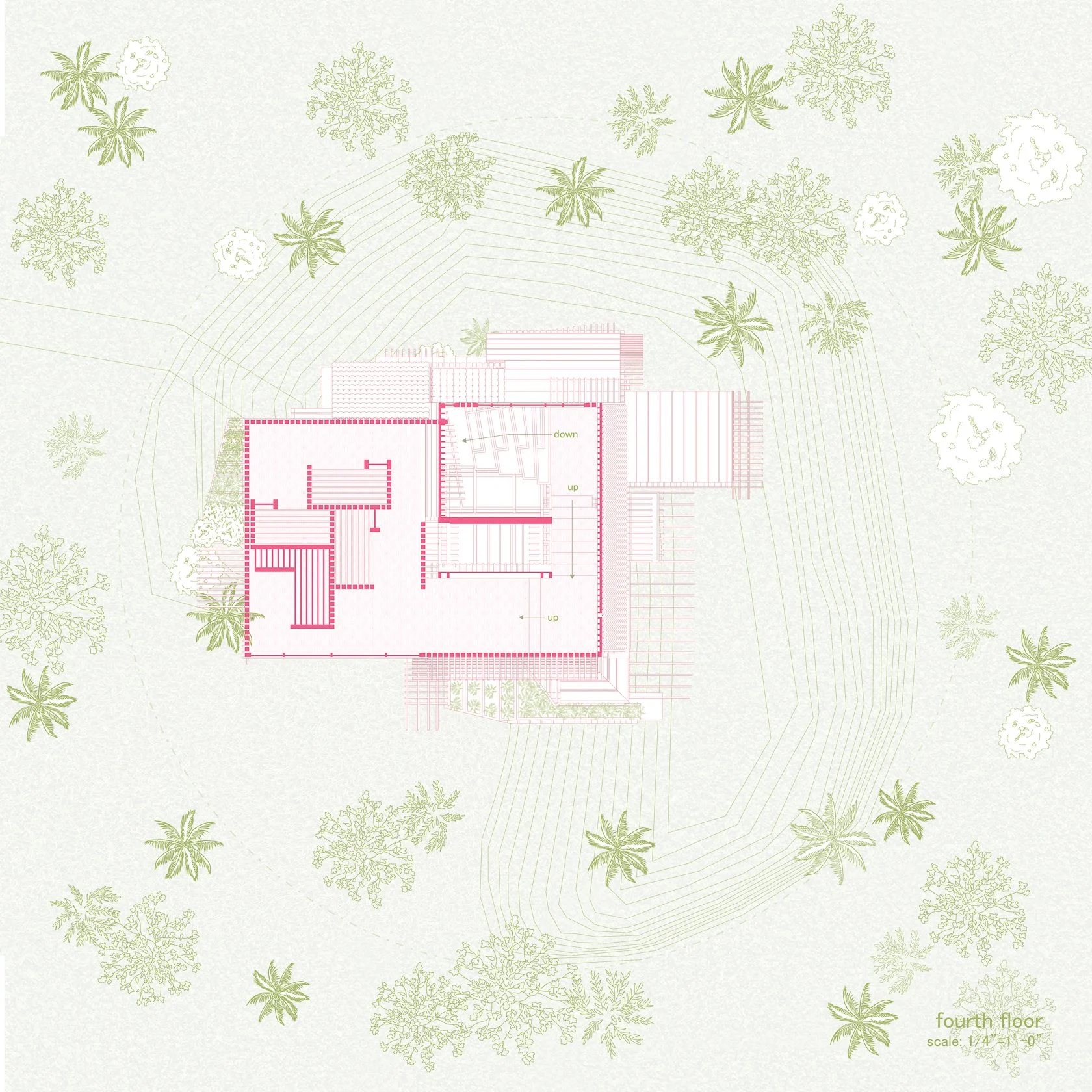

The Vernacular Sound

This project works to blend vernacular building techniques with magical realism. The building was designed by using different techniques of enclosure and overlapping multiple systems. Water and sound were the driving factors of design and ultimately influenced the overall form.

Antonio Sanmartin Gabas

The studio is dedicated to the design of NEW URBAN-CIVIC SPACES able to prompt and generate the NEW ARCHITECTURES of BARCELONETA, a privileged BARCELONA sea front neighburhood between the Medieval city and the water front with a dense and intense visitor’s enjoyment and pressure. The studio operates, investigates, and finds architecture practicing TRANSCRIPTIONS from ways of life, cultural specificities, and universals, from the already known to the still unknown, from the visible to the non-visible. Students will learn to find, describe, and build architectures found where “phase changes” between dimensions occur. Namely: IMPRESSION, PROJECTION, MEMORY and EXPERIENCE, INTELEGIBILITY, TRANSFINITE and METAPHOR. These TRANSCRIPTIONS will make the NEW URBAN-CIVIC SPACES and the resulting NEW ARCHITECTURES able to host HOUSING or co-HOUSING programs, CONVENTION SPACES, WORKSHOPS, RESTAURANTS, COMERCIAL areas and UNASSIGNED spaces. Architectures will be grafted ON, UNDER and OVER today´s “BARCELONETA”.

Carrying from one TRANSCRIPTION to the next the information found, elaborated or almost lost requires a position of suspending both the “belief” and the “disbelief” by students. Precision and literal description rather than personal interpretation is how meaning is built in architecture. We as architects (or as students) ARE NOT AT THE CENTER of IT. We all are necessary agents, but we are not the only units or parameters to measure it.

A CHRONICLE from the most recent to the oldest done in Studio; written in present tense is the last TRANSCRIPTION “drawn”. As if all is happening and being built during the time it takes to read it. One TRANSCRIPTION per week approx. All discontinuous tasks to research and explore a comprehensive set of explorations to be traced and slowly build the possible “meaning” the project may show and maybe share the joy for the unexpected. The studio embraces design as an ongoing process of interpretation and mistranslation advanced through the intensity of making and the rigor of iterative design with the lens of "uncanny" translations to discover new ways to investigate, imagine, and engage architecture with a contemporary sensibility.

Delan Lara

REGROWTH

This project began by investigating and then illustrating the “soul” of a previous studio project. What was identified as the “soul” of the project was “regrowth”—the idea that something once in decay can return healthy and strong. Transcription 3 and 4 were an exploration into the culture and essence of Barceloneta through the lens of a speech given by the famous violinist Yehudi Menuhin in 1997. Menuhin stresses the necessity to recover a sense of the “sacredness” of our lives. In his own words: “I think that the limit we have left to cross is not simply to reconcile religions. transcription 4 illustrates the essence of Menuhin’s message through several de pieces: the Periodic Table, a convergence of religiously significant architecture, context, place, symbols, atoms, molecules, limits, balance, and alternatives. Finally, a re ned project iteration was selected, and development of the nal design commenced. The drawing of the periodic table from Transcriptions 3 and 4 informed the private formal development of the project in section. Additional formal elements from those transcriptions—such as the integrated sections of religious architecture—were used as a structural “base” lightly touching the site, supporting the structure of the private program elements, The facade’s design was inspired by a sound frequency map generated from each element of the periodic table. These frequencies were translated into linework on a grid-like diagram, which informed both the aesthetic and construction of the façade. This pattern was later realized as kinetic, perforated aluminum ns that acted as shading devices for each apartment balcony. Through thoughtful formal development, material experimentation, and cultural sensitivity, the naliteration serves as a dynamic response to both place and purpose. It re ects a commitment to bridging social and environmental divides while honoring the sacred, communal, and regenerative aspects of human experience.

Aaron Muth

Sandbox

My architectural strategy originates from early investigations into vernacular Jamaican structures—thatching, wooden joinery, and elevated open spaces. These elements informed both material choices and a spatial approach rooted in phased construction. The final design utilizes over-engineered laminated 2x4s, joined with tongue-and-groove connections and timber dowels. This system enables modular attachments and makes staged building practical.

Modern elements like oculi for daylighting and framing views contrast intentionally with natural materials. The design evolved into a children’s residence, aiming to soften the institutional feel typical of such typologies. Inspired by playground forms and language, the architecture merges play and shelter, transforming an initial pavilion into a vibrant, engaging home. The color palette draws from Miami’s Art Deco pastels, while exposed dowels support adjustable louvers. These louvers animate the façade and respond to climate—opening by day for light and ventilation, and closing at night to protect the children.

The residence is structured as a vertical sequence of “mini floors,” scaled for children and increasing in privacy upward. Louvers double as railings, and outdoor decks serve as elevated zones for safe exploration.

Circulation is playful—swings and slides are integrated into the architecture, turning movement into joyful experience, and the overall site model draws from the idea of a sandbox—malleable and exploratory.

Ultimately, the project bridges Jamaican vernacular principles with pavilion-based methodology to create a child-oriented design that combats typical institutionalized spaces.

Jon Yoder

This advanced graduate design studio explored the scopic potentials of architecture. Through the iterative development of speculative landscapes and new vision machines that frame them, we learned that scopic pulsions—or irresistible urges to look—can be, and frequently are, designed by architects. Landscape observatories by Snøhetta, BIG and James Turrell, and camera houses by Le Corbusier, John Lautner and Diller Scofidio + Renfro, were only the beginning. As architectural image culture expands through virtual reality and social media, and drones and generative A.I. seem to achieve the longstanding anti-gravitational teleology of Modernism (with its floating eye-in-the-sky projections and impossible transparencies), there is no better time to question the contemporary status of images and propose provocative alternatives.

The projective, ocular-centric agenda of this studio was intimately bound up with the histories and possible futures enabled by visual media. If photography inspired radical experiments in 19th-century painting, and television triggered dramatic transformations in 20th-century cinema, how can generative A.I. platforms prompt compelling paradigm shifts in 21st-century architecture? In this ambitious studio, we used innovative approaches to modeling, rendering, animating, and fabricating to 1) investigate the historical vision apparata that created Modernist modes of human viewing; and 2) invent new vision apparata and speculative landscapes that create compelling new modes of posthuman viewing. Producing images of architecture in the landscape were no longer enough. “Scopic Pulsions / Architecture After Images” used architecture itself to produce profoundly seductive images of previously impossible landscapes.

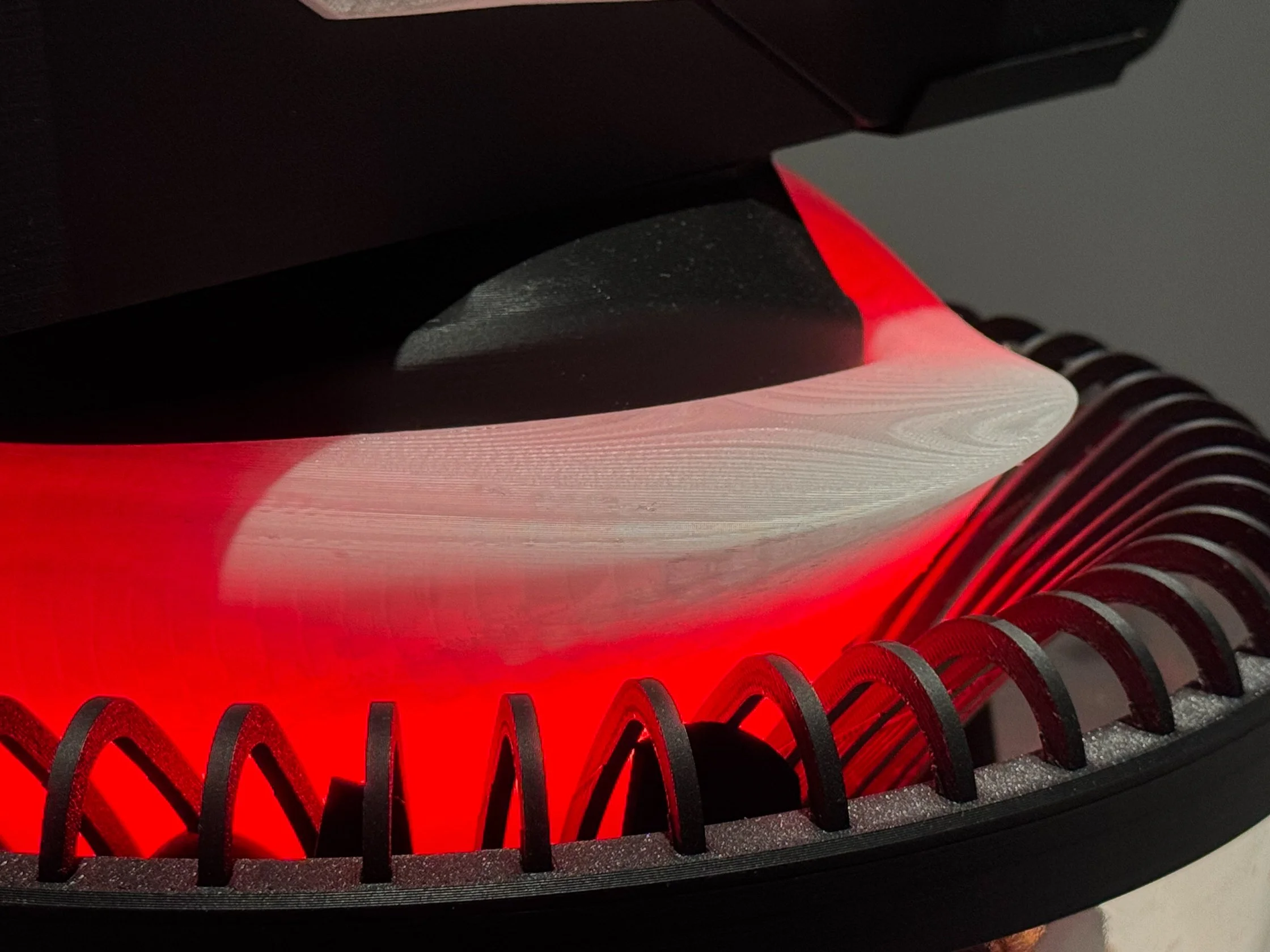

Aaron Rombach

Terrascope

This project is an experimental exploration focused on constructing an apparatus specifically designed to generate and contain a speculative landscape. This imaginative landscape exists exclusively within the confines of the apparatus, observable only through direct engagement with the machine. The distinctive form and structural characteristics of the apparatus play a critical role in shaping, influencing, and containing the internal landscape. While direct viewing necessitates interaction with the device itself, the landscape subtly emanates a luminous glow in low-light settings, intriguing observers and encouraging closer interaction. By adjusting the apparatus’s color palette and illumination intensity, users can continually alter and reshape the landscape, thus sustaining ongoing viewer interest and engagement. This dynamic flexibility ensures the speculative landscape remains responsive and captivating, providing a continuously evolving visual experience that explores the intersection between structure, perception, and spatial imagination.

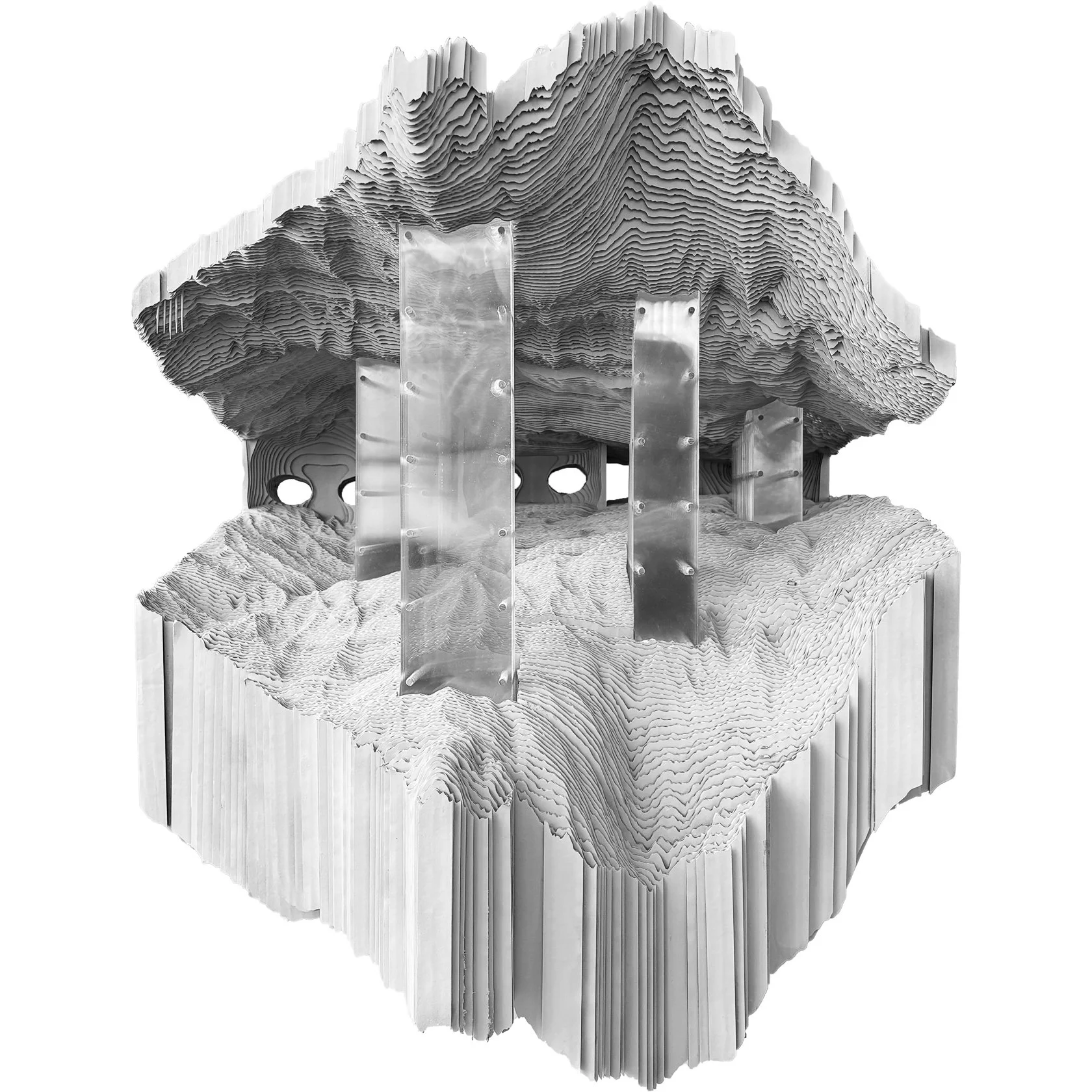

Ashley Aurand

Retinal Archaeology

Retinal Archeology investigates the scopic potentials of architecture by crafting a speculative landscape that reframes how vision, perception, and architectural experience intertwine. In this terrain, the project engages with the retinal surface as a limit condition of viewing, where vision is reduced to an interaction with images that flicker across the eye’s membrane, stripped of tactile, auditory, or spatial resonance. It proposes an architecture that does not merely represent the landscape but produces it through vision, making the terrain visible only through tightly orchestrated channels of light and shadow.

The project begins by carving optical channels through a vast, cavernous landscape, forcing the observer into designated scopic positions, allowing them to view what is above and what is below the line of sight. The terrain itself, composed of volumetric voids and vertical vegetation, functions like a vision apparatus: a device that both produces and frames seeing. These vegetal columns act as data lines, registering topographic variation and creating a scalar relationship between sight and landscape.

Ultimately, Retinal Archeology invites us to question what is seen and what is obscured. It does not reveal the world—it constructs it, layer by retinal layer, through an apparatus of pure scopic desire.

Tyler Cramblett

The Voracious Vision Dispenser

The Voracious Vision Machine is a playful, capsule-shaped robotic object. At first glance, it feels approachable. Its smooth white chassis and glowing interior suggest curiosity, interaction, and even amusement. Sized for the body, it seems built for human engagement. Visitors lean in, peer through the shifting pink and blue lenses, and begin to explore the unworldly landscape inside. The lenses zoom, tint, and distort, but they never clarify.

While it invites touch and attention, the apparatus quickly reveals a deeper ambiguity. It is not just an innocent device. It carries the presence of a device built for something more urgent. The longer one spends with it, the more it feels like a tool for navigating an unstable world. Its inspiration comes from Living Pod by David Greene, a compact survival capsule, and Walking City by Archigram, a vision of mobile architecture. Similarly, The Voracious Vision Dispenser is not just shelter but a system for life support within this landscape.

This duality between play and necessity, comfort and threat, is central to the project. The lenses do not reveal truth. They fragment, distort, and demand effort. Seeing becomes physical and uncertain, echoing Merleau-Ponty’s idea of voracious vision. The apparatus tempts the viewer but never lets them forget that in some future, vision itself might be a means of survival.

Parker Zaras

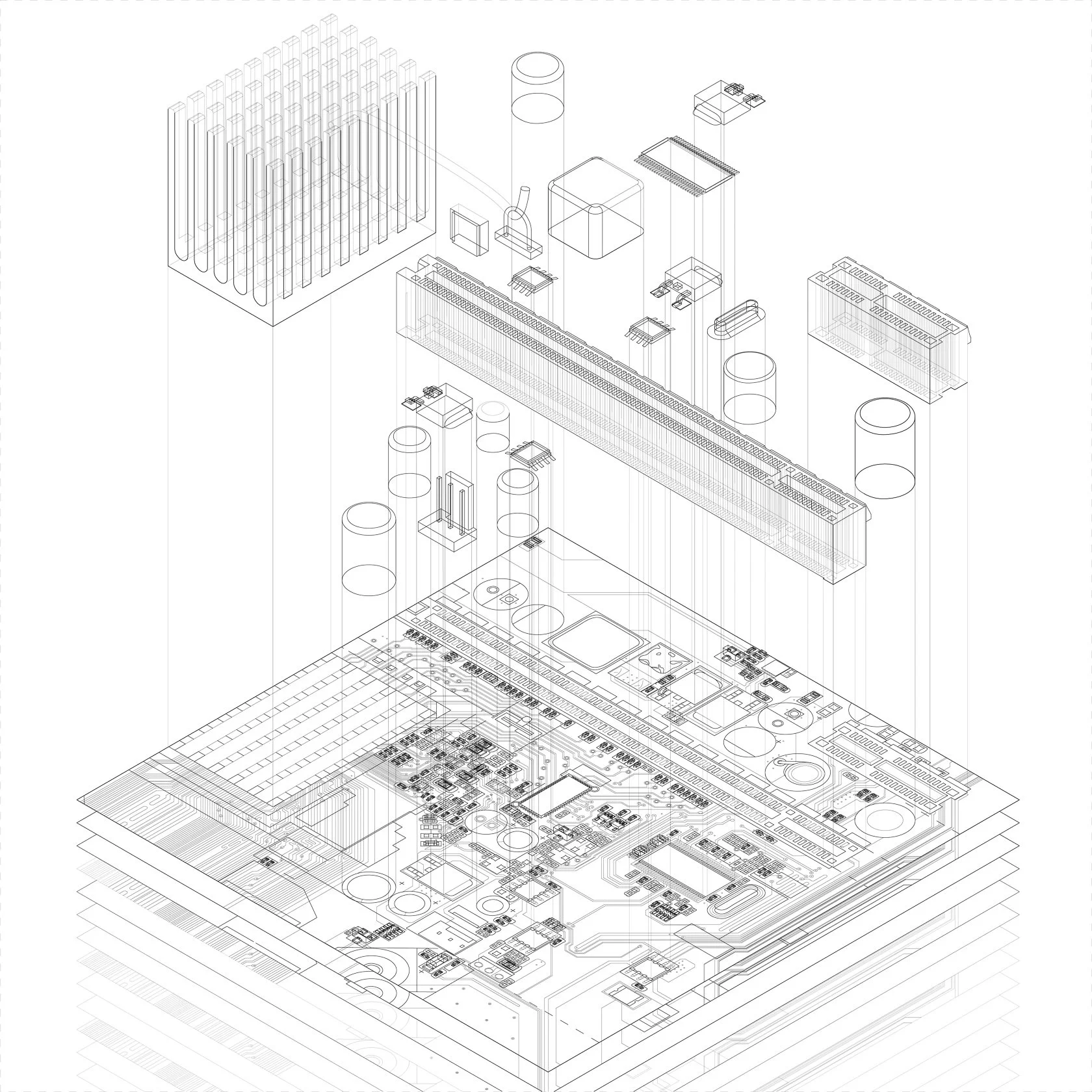

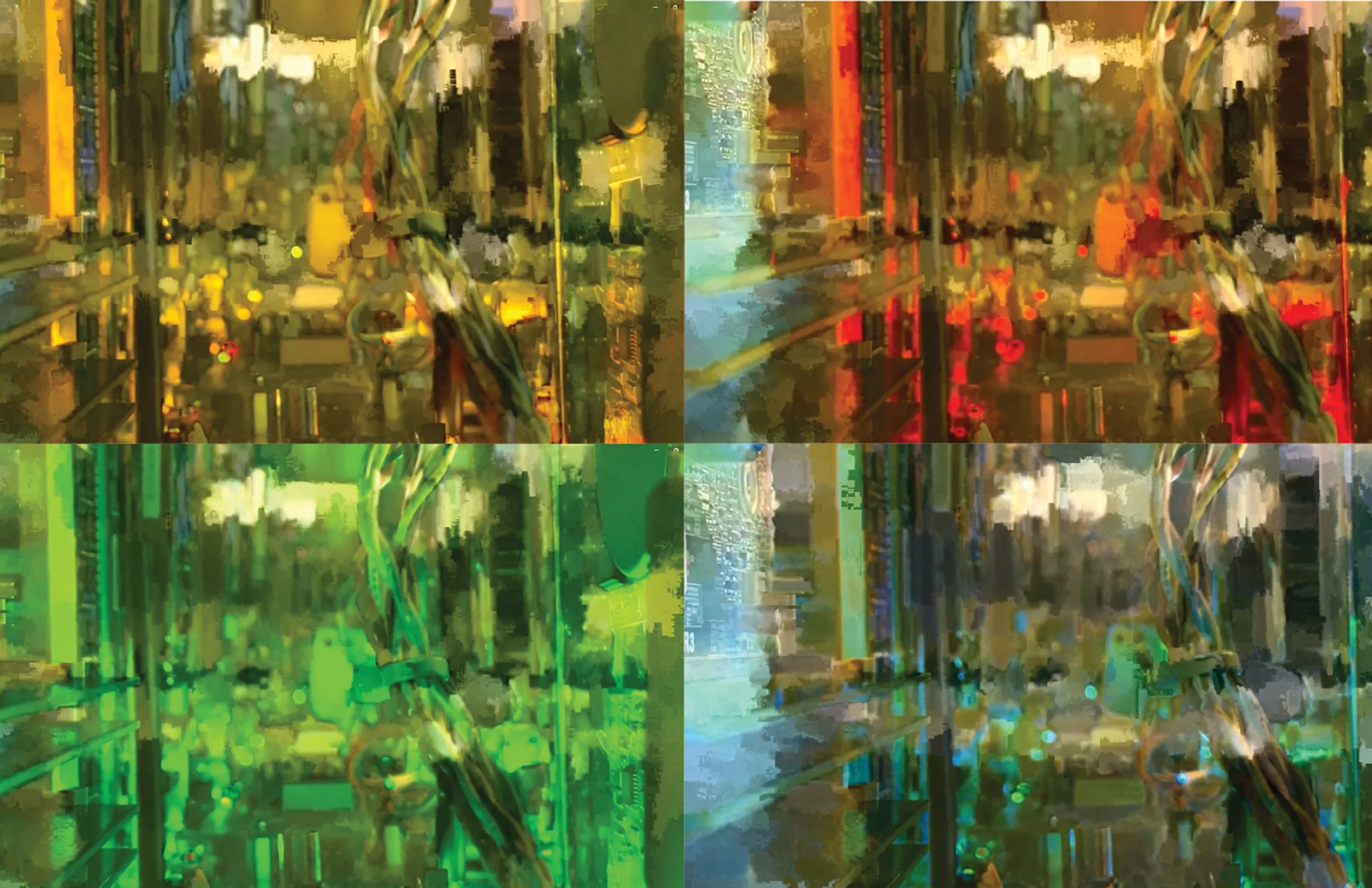

[RECURSIVE CITY]

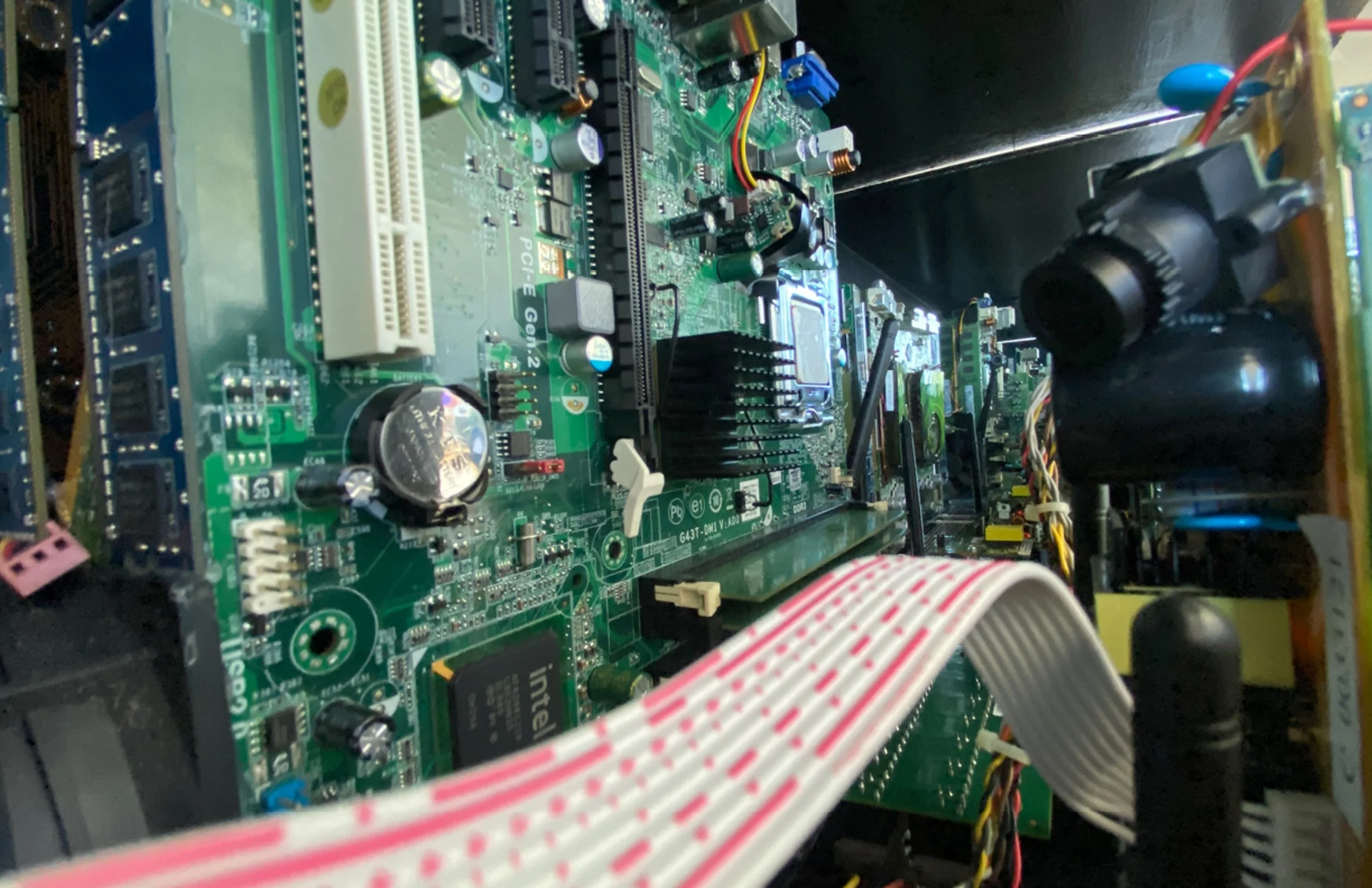

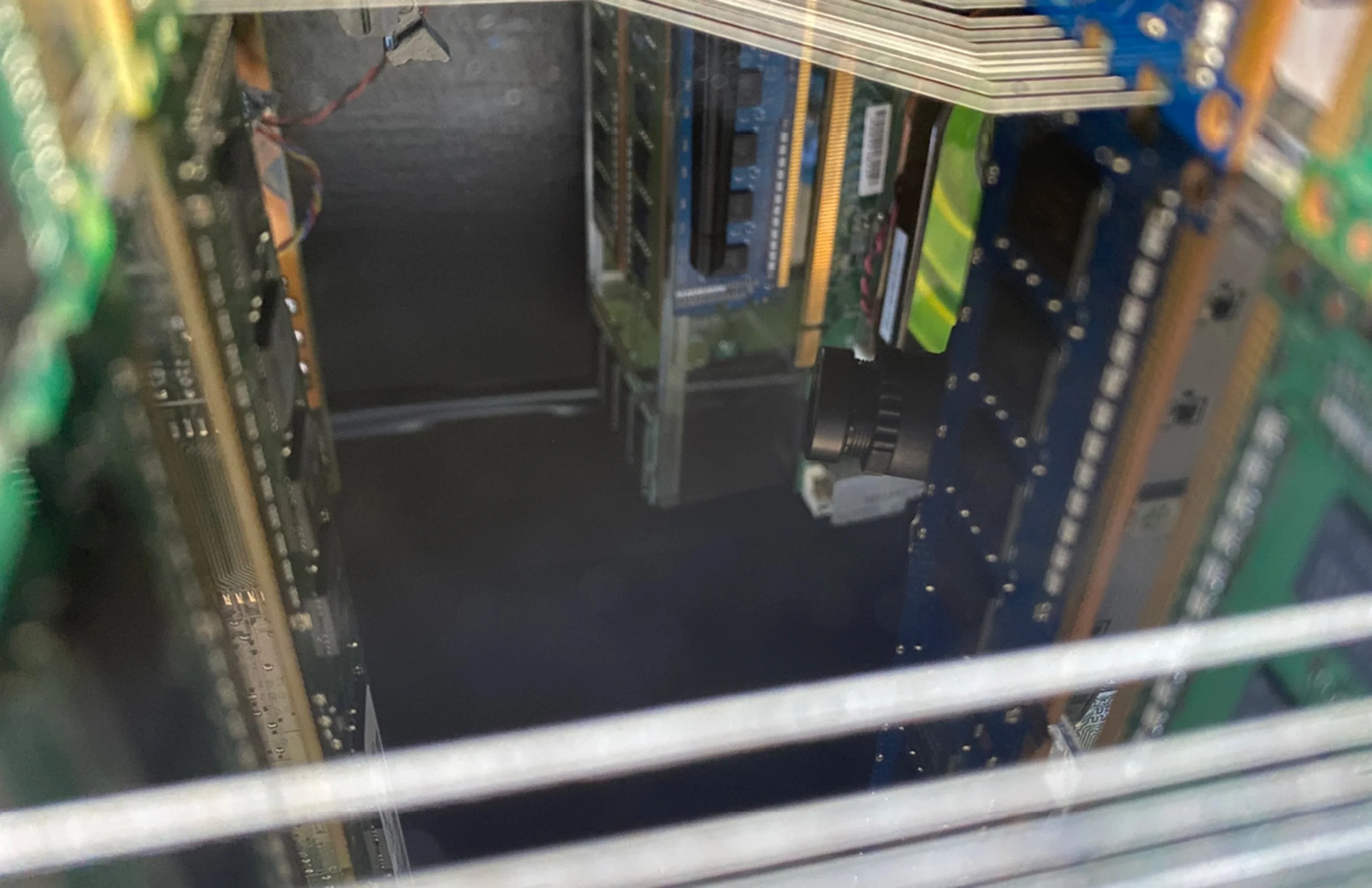

The Recursive City explores a speculative architecture formed not by human hands, but by circuitry —an ever-expanding digital terrain that generates and observes itself through embedded lenses. This project reimagines the act of city-making as a recursive operation, where cameras replace eyes and feedback loops replace intention. Within this artificial landscape, views are not constructed for human spectators but for the network itself—a machinic gaze perpetually directed inward. Each camera is embedded within the circuitry, capturing fragments of its own infrastructural body. These fragments become new inputs, prompting further architectural growth. The city becomes a closed visual system, seeing only itself, iterating on what it sees, and expanding accordingly.

This recursive process mirrors how humans historically build cities: we construct environments, frame views through windows, streets, and monuments, and then use those views to shape future developments. But unlike the human city, which seeks orientation, identity, or symbolism, this circuitry-based city is driven by blind feedback. Its cameras do not seek meaning; they seek signal. The resulting urbanism is one of pure self-reference—an endless architecture of mirrors made of data, copper, and silicon. As the project unfolds, we are left with a question: if architecture is defined by how it frames and reveals the world, what does it become when it frames only itself?

The Recursive City is both a spatial model and a philosophical provocation. It proposes a city that has no center, no user, and no outside—only a continuous loop of surveillance and self-production. Through a series of miniature circuit-based constructs and internalized views captured by low-resolution lenses, the project poses the question: What happens when the act of viewing becomes the engine of architectural form?

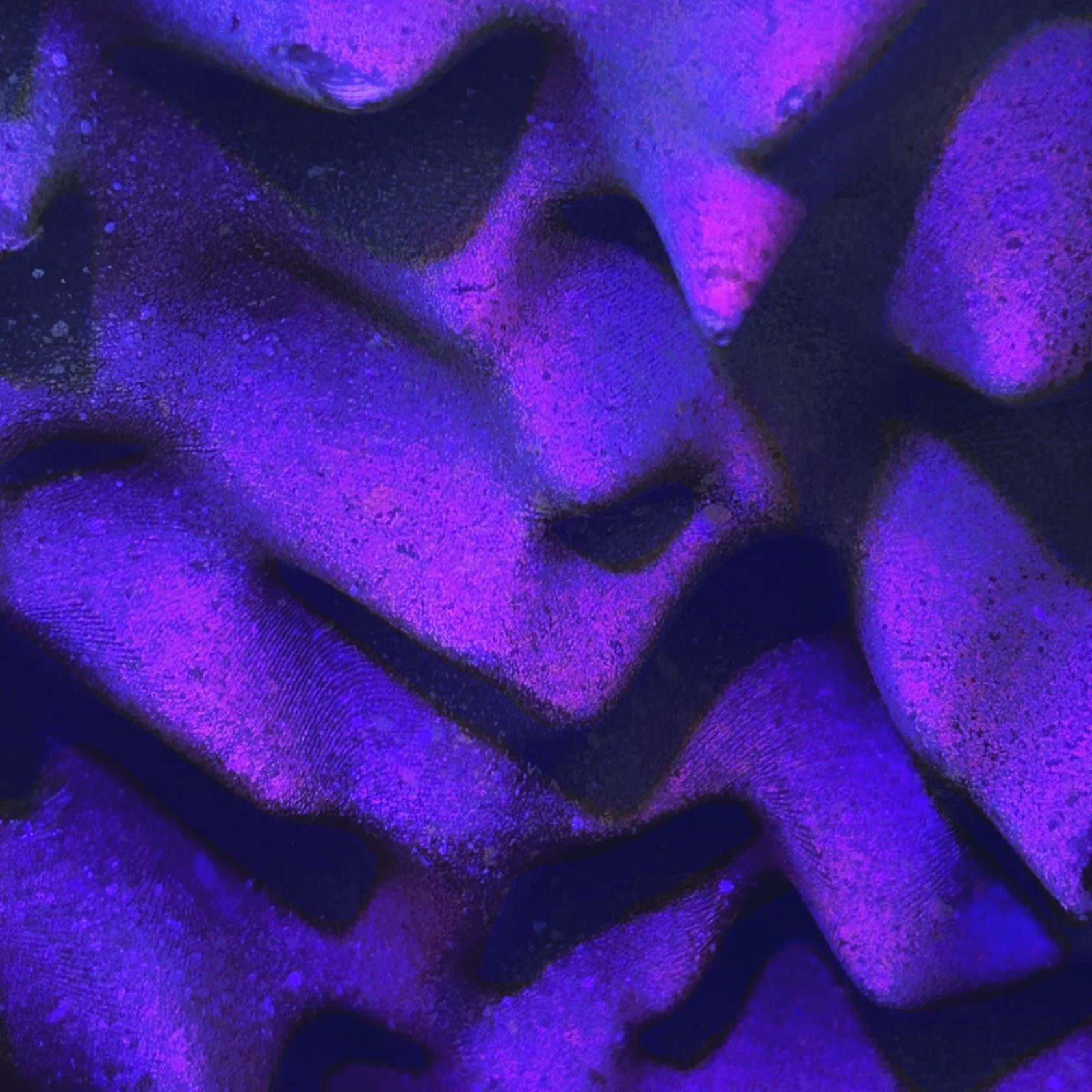

Morgan Gresko

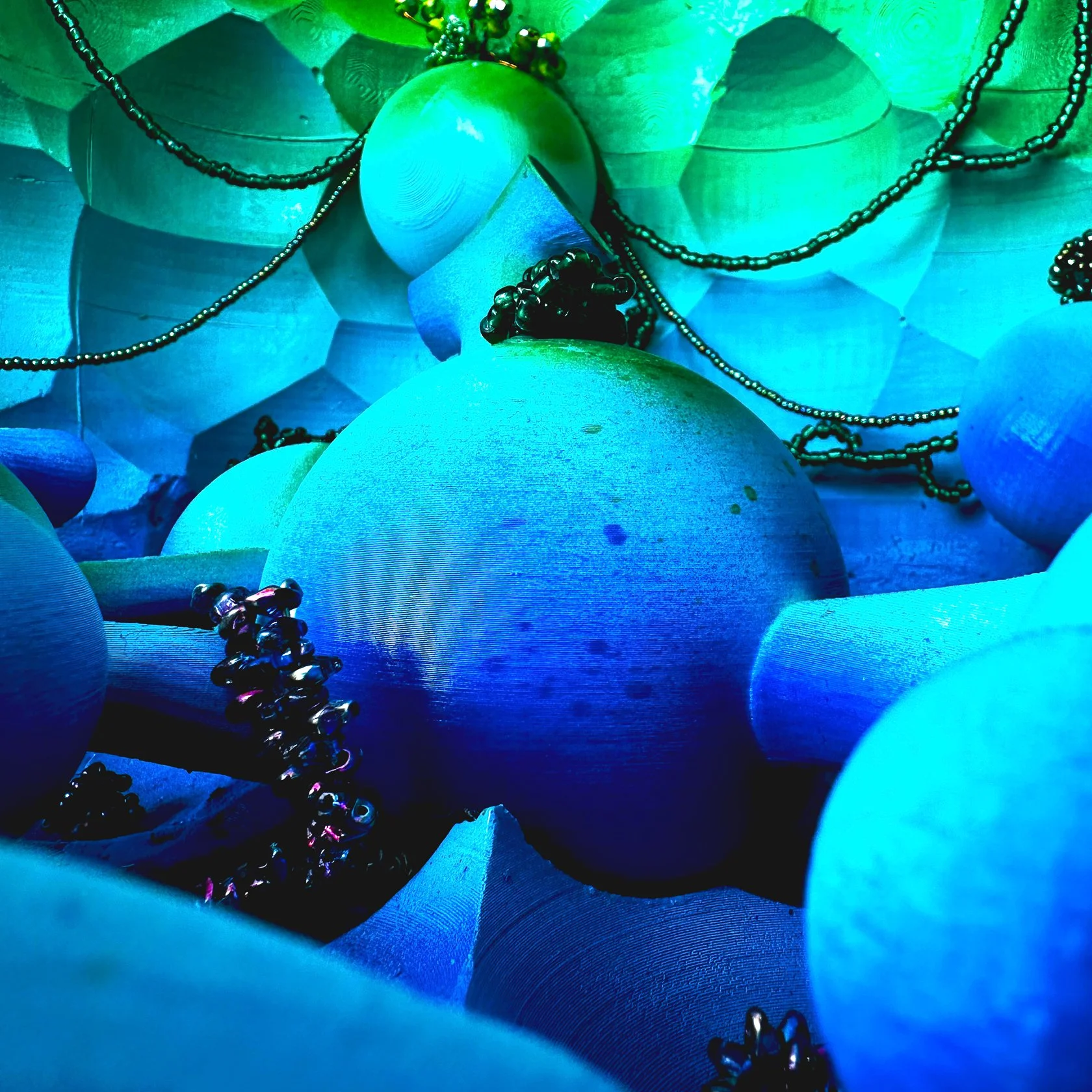

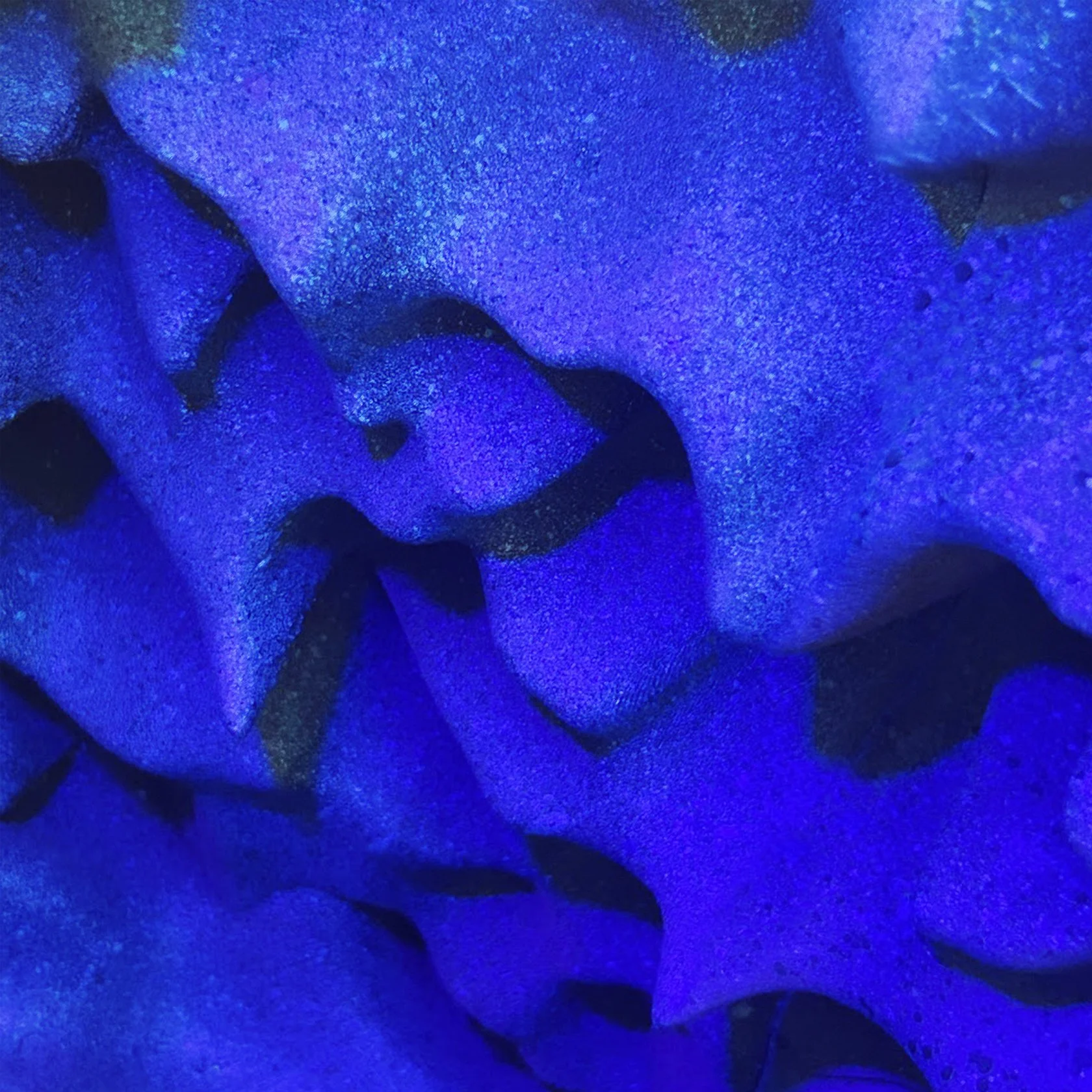

Miniaturizing Mutualism

The components that make up this project emerge in tandem with one another, manifesting themselves in a symbiotic relationship. The apparatus begins to take on a continuous, fluid form, inspired by Antti Lovag's Palais Bulles and Friedrich Kiesler's Endless House. The form breaks its continuous shape only to create viewing points to capture the surrounding landscape. Topographical aspects of the speculative landscape emerge from the spherical nature of the worm-like apparatus, becoming an inverse result of the bulbous form. This interaction further reinforces the idea that the landscape and apparatus cannot exist without each other. The concave shapes that construct the landscape also guide the viewer's eye deeper into the project. Tool paths that would normally be sanded away or hidden become the scalar patterning of the scape. Co-evolution of the bulbous and sparkly characters occurs in the environment’s geometry, patterning, and color. This ultimately produces an uncanny, whimsically miniature version of reality. Miniaturizing Mutualism challenges traditional architectural viewing by inviting the viewer to project (shrink) themselves down into the landscape rather than envisioning the model scaled up to the typical size of a building.